Hearing loss in the trenches – a hidden morbidity of WWI

The latest Paper of the Month from The Journal of Laryngology & Otology is ‘Hearing loss in the trenches – a hidden morbidity of World War I‘ by K Conroy and V Malik.

‘Modern warfare exercises its evil influence more on the hearing organ than on any other special sense.’ 1

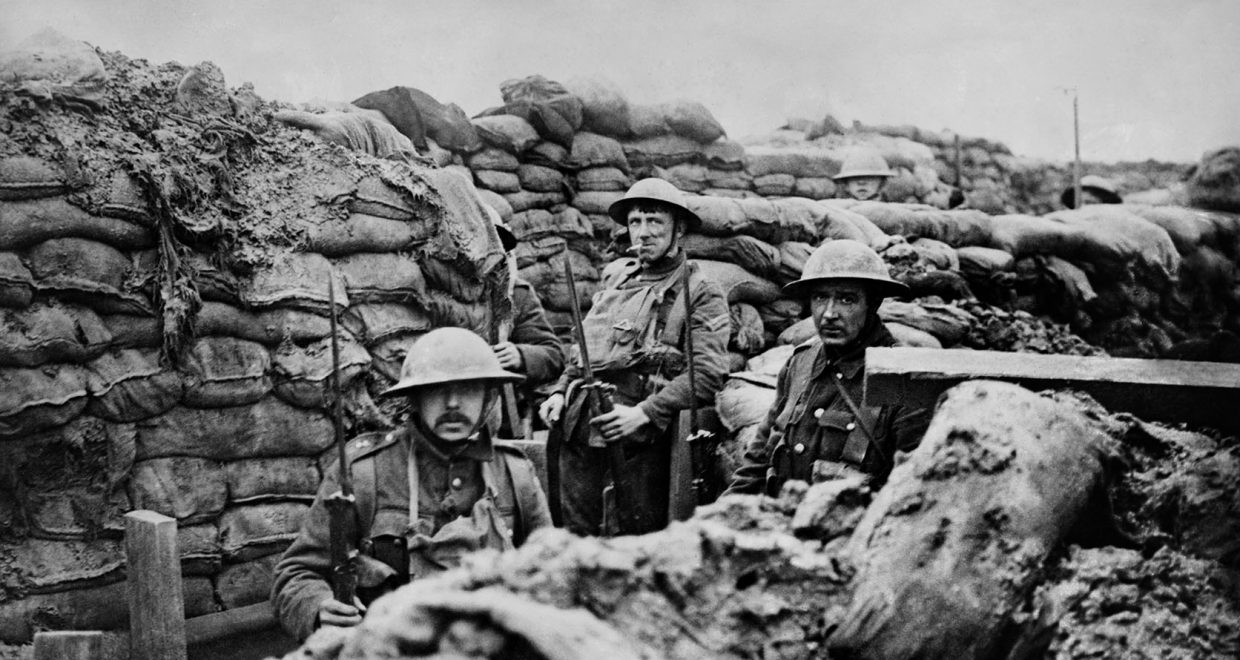

November marked 100 years since the conclusion of World War I, and the homecoming of millions of British and Allied troops. In a conflict where more than a tenth of soldiers lost their lives and diseases were rife, hearing loss was understandably a low priority, in an environment where fatal injuries and diseases were rife. However, in the decades that followed, it became apparent that vast numbers of troops had sustained significant hearing loss.

An examination of the literature published during and immediately after the war provides a fascinating insight into the prevalence of hearing loss in the trenches, and how this was approached by medical professionals.

Soldiers in World War I experienced aural pathology at twice the rate of the civilian population2, often due to noise-induced sensorineural hearing loss.

Advances in technology resulted in new, high-energy weapons generating sustained noise at levels which had never been experienced before; the Lochnagar mine, detonated at the Somme in 1916, was at the time the loudest sound known to man, and could be heard in London. The effect was a significant proportion of troops suffering from “labyrinthine concussion” or “soldiers’ deafness”.

Blast injuries to the tympanic membrane (often resulting in infection due to unsanitary conditions), direct trauma to the ear, non-organic hearing loss and malingering were also common.

One source estimated that 2.4 per cent of the army sustained a disabling level of hearing loss, and a further proportion went unreported because of other morbidities, or the prevailing sentiment of ‘getting on with it’.

With few otolaryngologists in the field and the challenges of following up patients it was difficult to assess and evaluate hearing loss. Because of a lack of understanding of its pathophysiology, many British doctors viewed labyrinthine concussion as a temporary affliction, and felt that a large number of soldiers were malingerers or ‘hysterical’. Poor results meant that middle ear surgery was discouraged in all but the most desperate of cases2. In summary, hearing loss was underreported, underdiagnosed and undertreated. Even so, by the end of the war, it accounted for 2% of all military pensions.

A century on, with a wealth of peer-reviewed evidence available to us, it is difficult to appreciate how these misconceptions regarding deafness in soldiers evolved, without examining the context in which they were formed. However, it is clear that noise-induced sensorineural hearing loss is still a major cause of morbidity in the armed forces, as well as in the general population.

1. McKenzie D. Letter to the editor, War Deafness. Lancet 1917;190:729

2. Dickie JK. Experiences of an otologist in France, 1915–1919. Can Med Assoc J 1921;11:893–9

Read the full article ‘Hearing loss in the trenches – a hidden morbidity of World War I‘ for free until February 14th.