10 things we learned about the History of Reproduction

As editors of Reproduction: Antiquity to the Present Day we brought together experts from several disciplines and challenged them to think about change and continuity in the history of procreation. Their contributions range from phallic fertility myths of the ancient Near East to global markets in donated eggs, from Roman marriage laws to struggles over abortion since the 1960s, and from ‘the monster of Cracow’ to cloned frogs. The result is a hefty, highly illustrated book, centred on Europe and its empires, that consolidates the field and opens it up. Here are ten things we learned:

- The 1960s to 1980s were crucial decades for the politics of reproduction, of reproductive technologies and reproductive rights. The histories written then have shaped understandings ever since, but those frameworks are ripe for revision.

- Pioneering histories projected back the concerns of the early feminist health movement, and thus focused on contraception and abortion. Though people have always sought to regulate their fertility, for most married couples, most of the time, producing healthy offspring was in fact the main aim.

- Childbirth has always been women’s business, but never exclusively so; men were also involved. The model of the mid-twentieth-century United States, where (male) obstetricians almost drove (female) midwives out of business, has distorted historical assumptions. Elsewhere, doctors and midwives collaborated more than competed.

- Infertility did not become a medical matter only in modernity. Rather, doctors began treating infertility in ancient Greece and have tried, often watched by families expecting heirs, to help couples have children ever since. What sets the modern experience apart is how—beginning before in vitro fertilization—quests for children became projects in medical consumption on a significant scale.

- Since the eighteenth century, ideas and practices have shifted from ‘generation’—the active making of humans and beasts, plants and even minerals—to ‘reproduction’—a more abstract process of perpetuating living organisms. Yet this was a long revolution, with a unified discourse of ‘reproduction’ articulated only during the decades of the fertility transitions around 1900.

- ‘Population’ thinking and practices also began in the eighteenth century. But those innovations were only the most important in a sequence of changes in relations between states and peoples, and of thinking about the ‘multitude’, that dates from antiquity.

- ‘Generation’ was itself ‘invented’ in the fifth century BCE. Over the following centuries, the framework spread and hardened into orthodoxy, and was then challenged as more voices made themselves heard.

- Generation was shared (unequally) between female and male, whether either or both were deemed to contribute seed. All ancient theories of procreation assumed that women were inferior. In these patriarchal societies, little was at stake when an elite man promoted one theory or another.

- The politics are very different now that science has a monopoly on knowledge and, at the same time, the audience is broader and the range of interpretations more diverse. For instance, scientists agreed in the 1870s that eggs and sperm contribute equally to reproduction, but textbooks wrote of passive eggs and active sperms through the twentieth century—and feminist scholars criticized them for it.

- Christians broke up the Roman sexual and procreative order. They argued, with increasing success, that the only legitimate sex was that intended to produce children within marriage; Islam took a somewhat more flexible view. The rise of scientific medicine notwithstanding, and contrary to expectations of growing secularization, religion still shapes even high-tech experiences and the politics especially of abortion and contraception.

This long view of reproduction reveals continuities we miss by concentrating on a mere century or two, while the very similarities make clearer the specifics of change. Showcasing the advantages of collaboration, our book invites others to join the conversation, to go deeper and to include more places.

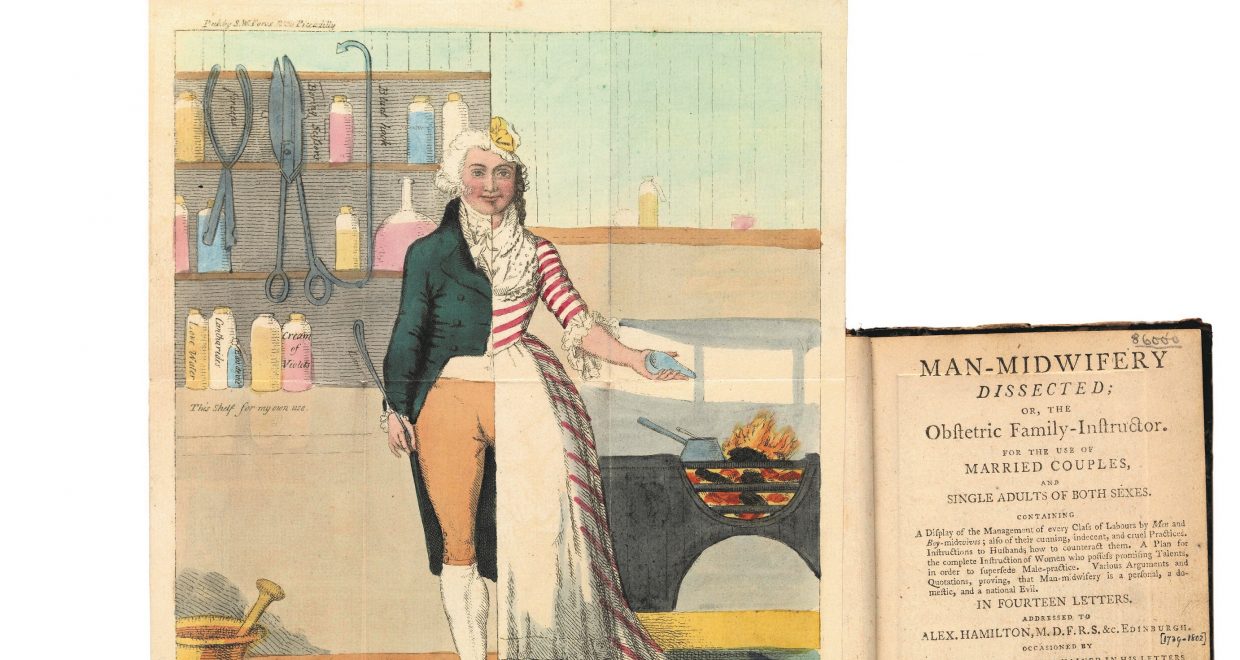

Main image: Extract from Exhibit 22 in Reproduction; Antiquity to the Present Day. Fold-out frontispiece (26 x 19 cm) and title-page (17 x 10 cm) to John Blunt [S. W. Fores, pseud.]. Man-Midwifery Dissected (London: S. W. Fores for the author [1795?]}. Wellcome Library, London, 22920/B.