How collections end: objects, meaning and loss in laboratories and museums

Collections are usually talked about in the heroic mode: collectors are ‘pioneering’, objects are ‘iconic’, displays are ‘powerful’. But, once assembled, collections tend towards decay. Living collections, in laboratories and zoos, end in death. The activities of the great collectors are called into question by those who see them as plunderers. Objects come to symbolize systematic injustice and colonial aggression.

The open access 2019 issue of BJHS Themes addresses the ‘endings’ of scientific collections, telling stories of dispersal, destruction, absorption, re-purposing and repatriation. The essays that make up the issue expose the intellectual, material and curatorial labour required to maintain collections, and the perpetual care, assessment, de-accessioning and editing needed for collections to persist. They explore what accidental losses, awkward relocations, recycling, repatriation and of dispersal tell us about scientific collections, their meanings and their power.

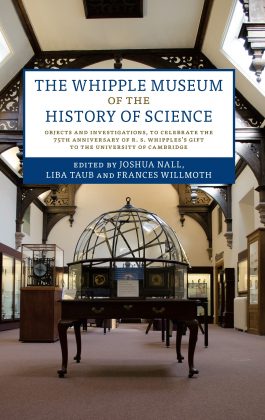

The papers were first shared at a workshop in the Whipple Museum of the History of Science in Cambridge, UK, and some of the reference points and case studies relate to the exceptionally rich collections (of scientific instruments, books, skulls, blood, statues) in the orbit of Cambridge (see, in particular Jardine). The essays also gather stories from Europe, the United States and the Asia-Pacific region on collections of seeds (Curry), microscope slides (Hopwood), blood (Roque), human remains (Kakaliouras), flies (Bangham), DNA samples (Skinner and Wienroth) and things that were never intended for collection, including museum props (Kowal), impromptu collages (Gómez López) and even museum catalogues themselves (Porter).

They consider objects that have been packed up, moved around, unpacked, repacked, stored, display, loaned out, returned, catalogued, recatalogued, lost, found, photographed, scanned, described, published, replaced, faked, stolen, that have decayed, been conserved, and decayed again. The essays in this issue find that to pay attention to ending is to pay attention to the shifting fortunes of things, to the labour of their maintenance, and to the reality of dispersal as a negative and positive force.

Together, they show that when collections end, so do careers, communities, disciplines, and empires, and that those broader stories have enduring social, political and intellectual consequences. Moving between the laboratory, the museum, and the difficult-to-classify spaces in between, they show that ‘ending’ is not anathema to ‘collecting’ but is always present as a threat, an everyday reality, or even as a necessary part of a collection’s continued existence. A focus on ending draws attention not only to the complex internal dynamics and social contexts of collections, but also to their roles in producing scientific knowledge.

——–

Articles in the volume:

Introduction – How collections end: objects, meaning and loss in laboratories and museums, Boris Jardine, Emma Kowal, Jenny Bangham

The blood that remains: card collections from the colonial anthropological missions, Ricardo Roque

Spencer’s double: the decolonial afterlife of a postcolonial museum prop, Emma Kowal

The repatriation of the Palaeoamericans: Kennewick Man/the Ancient One and the end of a non-Indian ancient North America, Ann M. Kakaliouras

Was this an ending? The destruction of samples and deletion of records from the UK Police National DNA Database, David Skinner, Matthias Wienroth

Living collections: care and curation at Drosophila stock centres, Jenny Bangham

From bean collection to seed bank: transformations in heirloom vegetable conservation, 1970–1985, Helen Anne Curry

The tragedy of the emeritus and the fates of anatomical collections: Alfred Benninghoff’s memoir of Ferdinand Count Spee, Nick Hopwood

On taphonomy: collages and collections at the Geiseltalmuseum, Ana María Gómez López

Catalogues for an entropic collection: losses, gains and disciplinary exhaustion in the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow, Dahlia Porter

The museum in the lab: historical practice in the experimental sciences at Cambridge, 1874–1936, Boris Jardine

Main image: Holland House library after an air raid, 23 October 1940