Revisiting a strange Silurian crustacean with a tangled past and persistent questions

Modern day crustaceans, including lobster, shrimp, crayfish, and crabs, are perhaps most familiar from our dinner plates. They, along with less familiar forms such as isopods (your garden pillbugs), belong to the huge living group Eumalacostraca, which includes some tens of thousands of species. The closest living relatives of the Eumalacostraca are the small phyllocarids (Phyllocarida), with only some forty species. During the Paleozoic, however, phyllocarids were one of the most important crustacean groups, dating back to Cambrian. Some reached sizes to rival modern day lobsters. Because they lacked the heavy calcification of other crustaceans, fossil phyllocarids are relatively rare. In this paper, we redescribe what may be the strangest member of the group, the genus Gonatocaris from the Silurian.

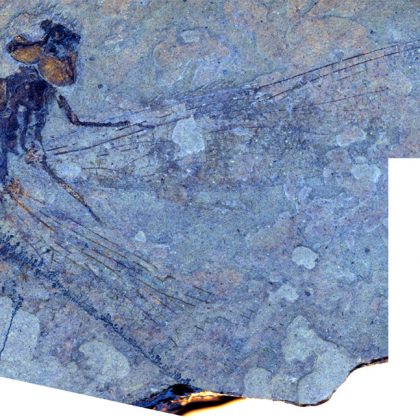

The species Gonatocaris decora was originally described in 1901 from a site in Pittsford, New York, USA, that was excavated during the construction of the Erie Canal. The shales from this locality belong to the locally restricted Pittsford Shale member of the Late Silurian Vernon Formation and are best known for containing diverse and abundant eurypterids (sea scorpions). Gonatocaris decora is the only common phyllocarid from the locality; this is also the only locality this species is known from.

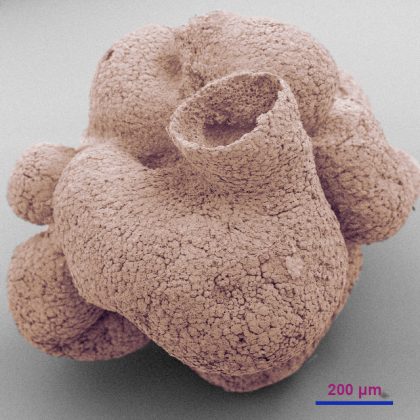

Until now, this species was only incompletely understood. We used extensive collections made over the past century and new imaging methods to redescribe it and to reconstruct what a complete animal looked like. What makes it remarkable is the reinforcement of the cuticle of the exoskeleton of the animal. The structure covering the head, the carapace, is crossed along its length by thick lines, which intersect and branch like the veins on an insect’s wing. The tail area, the abdomen, is covered by raised scales. Although related forms also have lines on the carapace, Gonatocaris is unique for the thickness of the lines, raised well above the surface.

Why is the animal so reinforced? One hypothesis is that it served to anchor the animal in the sediment, preventing a predator from pulling it out. We tested this experimentally, using a force meter to pull models of the animal, both with and without the exterior ornamentation. We found no difference, so we rejected this hypothesis. Instead, we suggest that the ornamentation strengthened the exoskeleton, as protection against being crushed by the predatory eurypterids.

Another oddity of this phyllocarid is its preservation. In life, each animal has a single bivalved carapace, seven abdominal segments, and a bifurcated tail. None of the fossils we studied was of a complete individual. Remarkably, the vast majority of specimens are isolated carapaces, often preserved in large aggregates, with a limited range of sizes. There are a marked paucity of abdominal segments and almost no tail pieces. We suggest several possible explanations for this, including molting behavior and predation (predators discarded the carapaces and ate the rest of the animal; we call this hypothesis “peel-and-eat”).

An additional strangeness of this species is the convoluted history of its name. It was originally named Emmelezoe decora, with Emmelezoe being a genus of phyllocarid described from England in 1887 and containing four species. In 1929, the new genus Gonatocaris was created for the material from New York. As part of this study, we re-examined the original specimens of Emmelezoe from England and decided that all of them belong to another genus altogether. Emmelezoe was left as a genus with no species!

A final mystery is the distribution of Gonatocaris in space. In addition to G. decora from New York, there are species of Gonatocaris in South China. Even during the Silurian, these sites were far apart; there are no known occurrences in between. Whether ocean currents carried the animals between the two regions, or they were present, but not preserved, in intervening areas cannot be determined.

The full paper “Redescription, paleogeography, and experimental paleoecology of the Silurian phyllocarid Gonatocaris” by Joseph H. Collette and Roy E. Plotnick is published in Journal of Paleontology and is freely available for a limited time here.

Read other blog posts from Journal of Paleontology here

or view all blog posts from the Paleontological Society Journals