Reconstructing a Cambrian Swiss Army Knife: The Claws of Stanleycaris

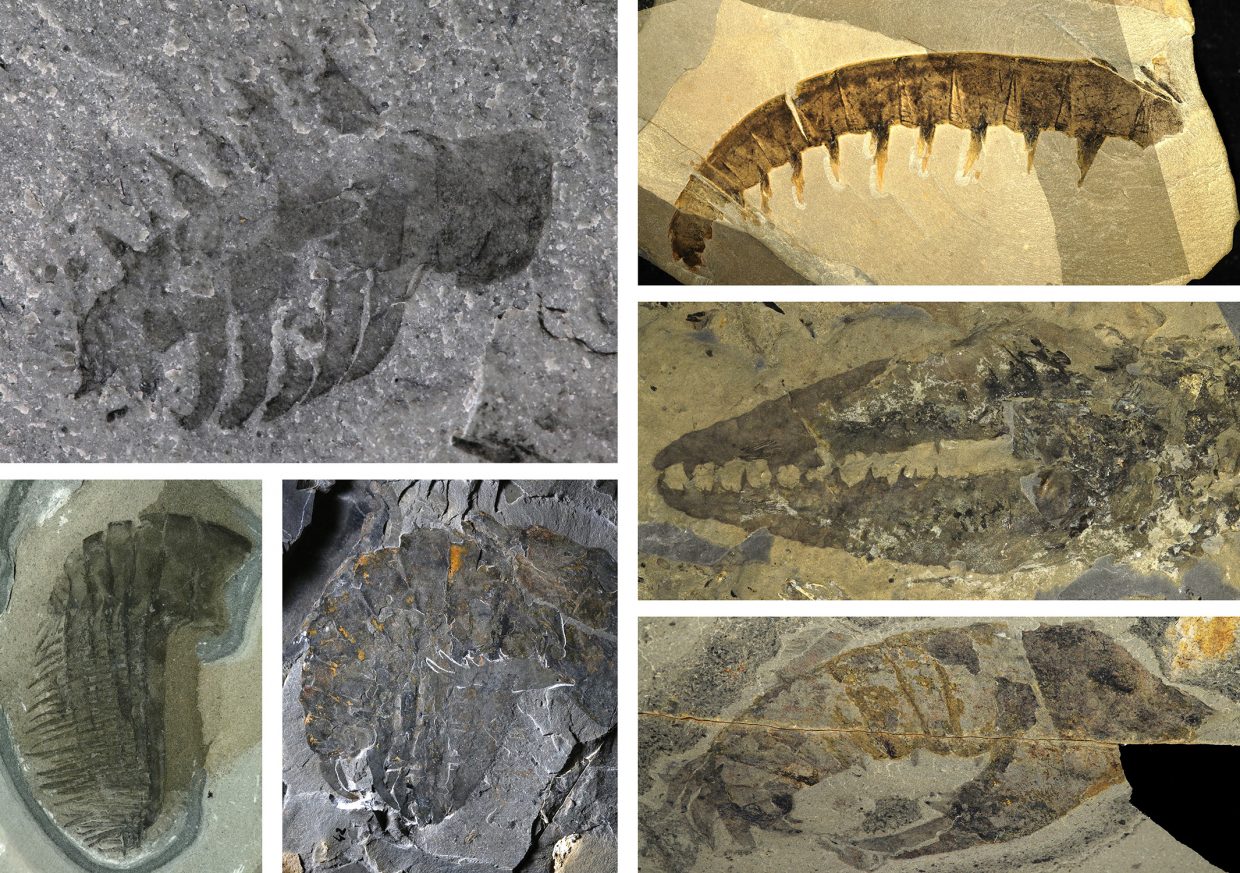

Perhaps no Cambrian invertebrate can claim greater public enthusiasm than Anomalocaris. Not only is it bizarre looking – the story of its discovery, being pieced together from fragments thought to belong to different animals, is uniquely compelling. Anomalocaris is not simply a one-off oddball, however. It belongs to an extinct group of arthropods, called radiodonts for their distinctive, radial, toothed mouthparts.

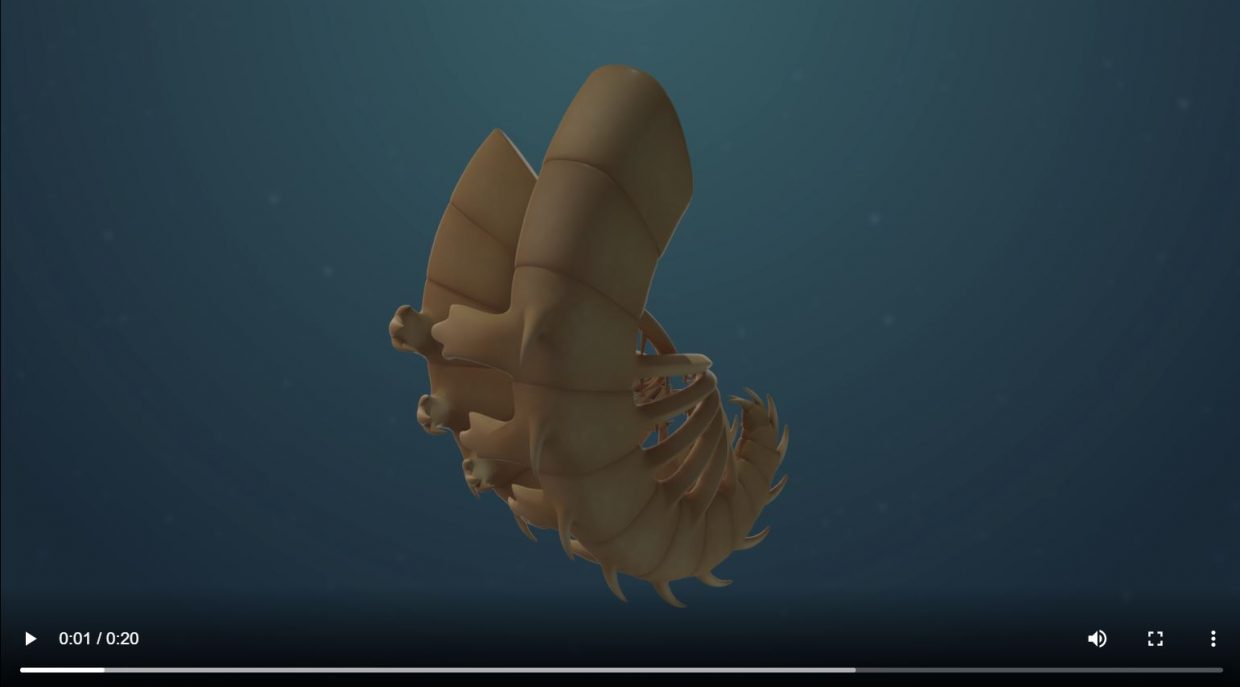

My coauthor and colleagues first published a brief description of another radiodont, Stanleycaris hirpex, in 2010, alongside the description of a new deposit of the Burgess Shale at Stanley Glacier, its namesake. Only the claws and mouthparts of this species were discovered, yet it was evident that they were different from other species known to date. Stanley Glacier turned out to be the veritable tip of an iceberg in Kootenay National Park, with subsequent discoveries of expanses of new outcrops that we’ve just begun to explore and understand. Between new species recovered there and myriad other finds from around the globe, we now recognize that radiodonts were diverse in space and time, as well as in the ecological niches they occupied. Species like Anomalocaris were streamlined predators with long grasping claws, but others crushed hard-shelled prey between scissor-like limbs or tore apart unfortunate animals with their pincers. Still others were bottom-dwellers with large, elaborately shaped plates covering their heads and used long comb-like spines to sift smaller organisms from mud or the water column.

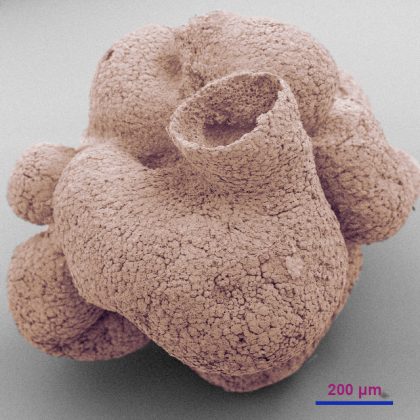

But how did Stanleycaris fit into this menagerie? After collecting new claws and mouthparts, we decided to take another look. After scrutinizing numerous flattened specimens, preserved in differing orientations, we realized the complex 3D form of the claws, including features that had not been appreciated before. Each is long and tipped with smaller hooked spines, resembling the ends of the grasping claws of Anomalocaris, but also bears a compliment of rake-like inner spines. Stanleycaris additionally possesses a third set of spines, shaped like curving tridents, which would have projected towards each other across the midline. Owing to their unusual orientation, these spiny margins could only have functioned together as a jaw, closing together to crush and tear prey before passing it to the fearsome tooth-rimmed mouth. Some distant arthropod relatives, like crustaceans and insects, independently evolved a pair of appendages that form biting jaws – mandibles – which are broadly similar in form and function. Given how divergent radiodonts are from these modern kin in other respects, the discovery of such striking evolutionary convergence in jaw form was a surprise, exemplifying the phase of heightened innovation that took place in the Cambrian. The coexistence of many different types of armament in a single claw is also remarkable, as radiodonts normally have a more limited variety of spines.

To examine this further, we adapted an index to measure the diversity of spiny protrusions on the frontal claws of early arthropods, a proxy for the range of functional roles they may have played. We then reconstructed the evolution of this index to see if a pattern might emerge. Sure enough, Stanleycaris and related forms help to link radiodont species that grasped mobile prey with those that specialized in sweeping up smaller organisms. We think that having multifunctional claws may have provided the evolutionary opportunity needed to hurdle the gap between these more specialized feeding ecologies.

While the claws and mouthparts of Stanleycaris are now known in all their glory, the puzzle of its other body parts has yet to be solved. Given its placement in the radiodont evolutionary tree, Stanleycaris has much yet to reveal about how the fascinating variety of radiodont forms evolved.

The full paper “Exceptional multifunctionality in the feeding apparatus of a mid-Cambrian radiodont” by Joseph Moysiuk and Jean-Bernard Caron has been published in Paleobiology and can be viewed here.

Read other blog posts from Paleobiology here.

or view all blog posts from the Paleontological Society Journals