The Pandemic has taught us to spend more time focusing on “the things that really matter.” But how do we know when something really matters?

The awareness that our lives can be abruptly shortened or seriously disrupted by unforeseen circumstances is a wake-up call that requires each of us to reflect on how we spend our time.

But how can we tell the difference between time-filling and time-fulfilling activities and experiences? The good news is that we all have a natural, evolved mechanism for doing just that. As we explain in our new book, Motivating Self and Others: Thriving with Social Purpose, Life Meaning, and the Pursuit of Core Personal Goals, humans developed the capacity for experiencing a special feeling – a feeling we call life meaning – that is designed to give us feedback related to the things we care about the most. Things like seeing your children or grandchildren laugh and learn and grow. Or becoming absorbed in an engaging task and seeing progress and accomplishment. Or finding a cause that excites you as you see yourself making a positive difference in the world. These are the kinds of experiences that stand out in our life journey and help fuel our goal pursuits.

Life meaning is a distinctive feeling that arises when a person believes that their life makes sense, has purpose, and is worthwhile.

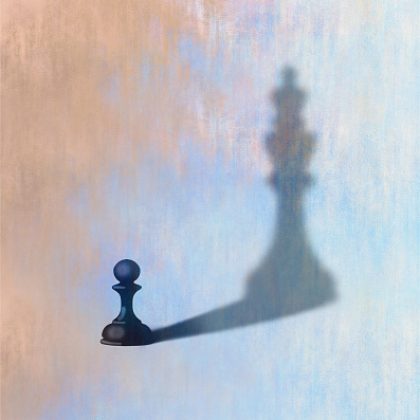

While the capacity to experience life meaning is innate, the specific pathways that are most likely to lead to these feelings is an acquired process. Life meaning is thus something we create, not just something that is given to us.

This naturally leads to the question: What are the most reliable sources of life meaning in the lives of humans? The Thriving with Social Purpose Theory of Life Meaning identifies seven evidence-based pathways through which people are most likely to experience feelings of life meaning:

Personal identity refers to the process of constructing self-concepts and autobiographical themes that feel natural, authentic, and worthy of a strong emotional commitment. Life tasks and challenges related to identity development may be experienced in many different domains — for example, career development, racial and ethnic identity, and family and gender roles.

Another pathway to life meaning is one in which people invest their time and energy in an ideology or philosophy that feels intellectually authentic and emotionally satisfying. For example, “conservative” and “liberal” belief systems provide us with explanations for how people should be governed, how resources should be distributed, and what kind of societal practices should be permitted.

People can also find life meaning through culturally defined values and ethical principles that offer motivational clarity and energy because of their alignment with an individual’s core personal goals. Embracing such ideals can be a source of security and inspiration, as illustrated by people who devote their lives to serving others, pursuing social justice, or striving for excellence in a culturally valued arena.

Religiousness is a pathway to life meaning through which people invest themselves in organized belief systems about God, divine universal powers, and how the way we live our lives relates to those transcendent influences. Religiousness also suggests conformity to religious practices that demonstrate a person’s faith in those beliefs.

Spirituality is a related but more individualized pathway that reflects efforts to define ourselves as a part of humanity. Why are we here? What is our destiny? How should we live our lives? People often look to religious beliefs and doctrines to provide meaningful answers to these questions, but we can also rely on insights from other sources of wisdom and inspiration — for example, accumulated scientific knowledge or compelling explanations from sage elders.

People can also derive life meaning from uplifting experiences that are particularly memorable due to the magnitude and elevating quality of the emotions associated with those unique life episodes – emotions like awe, wonder, and fascination. These special experiences help us understand ourselves and our place in the world through mechanisms that are more visceral than reflective (e.g., seeing awe-inspiring works of nature or human achievement; experiencing profound insights about ourselves or people we feel close to).

Although it is evident that we can derive life meaning from powerful ideas and special experiences like those outlined above, the primary source of life meaning in our everyday activities is goal-life alignment. When our daily lives at work, with our family and friends, and in our leisure time provide us with ample opportunities and encouragement to pursue our core personal goals (https://apg.gmu.edu), we feel both a sense of personal integrity and a “goodness of fit” with the world around us (e.g., “This is what I was meant to do”; “This is where I belong”).

Why Knowing the Things that Really Matter Can Matter So Much

The capacity to experience feelings of life meaning evolved because those feelings help us to survive even the worst forms of adversity and to thrive when opportunities arise to improve life for ourselves and others. Life meaning fills us with vitality and strength that we can draw upon time and time again, in good times and bad. Moreover, ample evidence indicates that life meaning can not only help us make our lives better, it can also help us live longer by persistently reminding us that life is indeed worth living. The pursuit of life meaning can thus serve as a powerful antidote to the stress and trauma associated with the pandemic, while also providing a pathway for creating upward spirals of accomplishment and well-being.

Very inspirational.