Apartheid Opera and the Politics of the Ordinary

South Africa’s apartheid history is still largely narrated as a tale of heroes and villains. Historical accounts venerate those who resisted the regime, and demonises those who enforced its racialised structures. The soundtrack of this history is likewise often construed as a struggle between the competing musical cultures of black protest and white conformity. But what are we to do with stories that do not fall neatly into those categories? How do we come to terms with cultural and political agents whose actions seemed to be at once complicit with the regime, and resistant to it?

One historical instance of such political ambiguity is the Eoan Group, a welfare organisation that worked among the so-called ‘coloured’ communities of the Western Cape between 1933 and the early 1980s. ‘Coloured’ is a racial classification that was codified under apartheid rule. It referred to those individuals who could not, by law, be classified strictly as black or white. The coloured racial designation included mixed-race individuals; descendants of the country’s imported slaves or of the indigenous Khoekhoe and San groupings found in the southern parts of the country; and until 1961, members of the country’s Asian migrant populations (‘Asian’ or ‘Indian’ subsequently became a separate race category). Coloured people, like the country’s black population, were excluded by their race from the civic rights and freedoms South Africa’s white citizens took for granted.

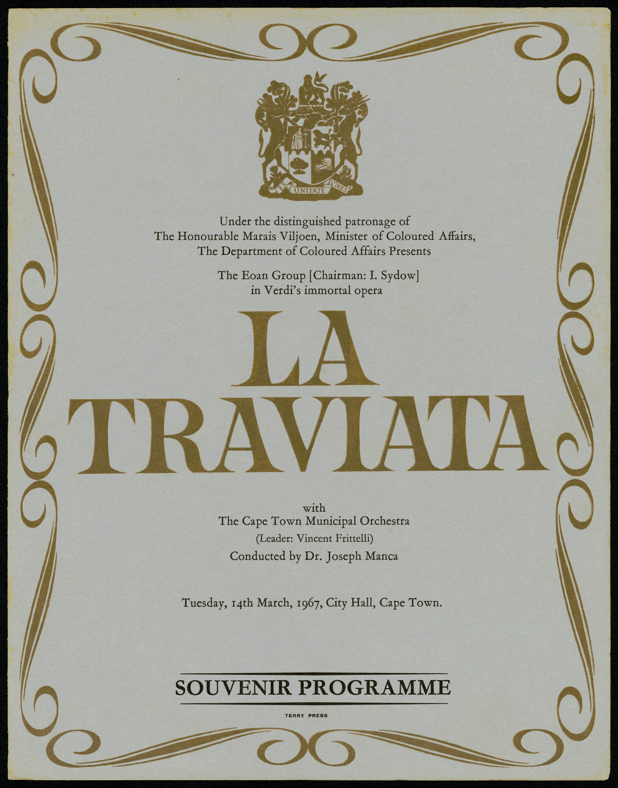

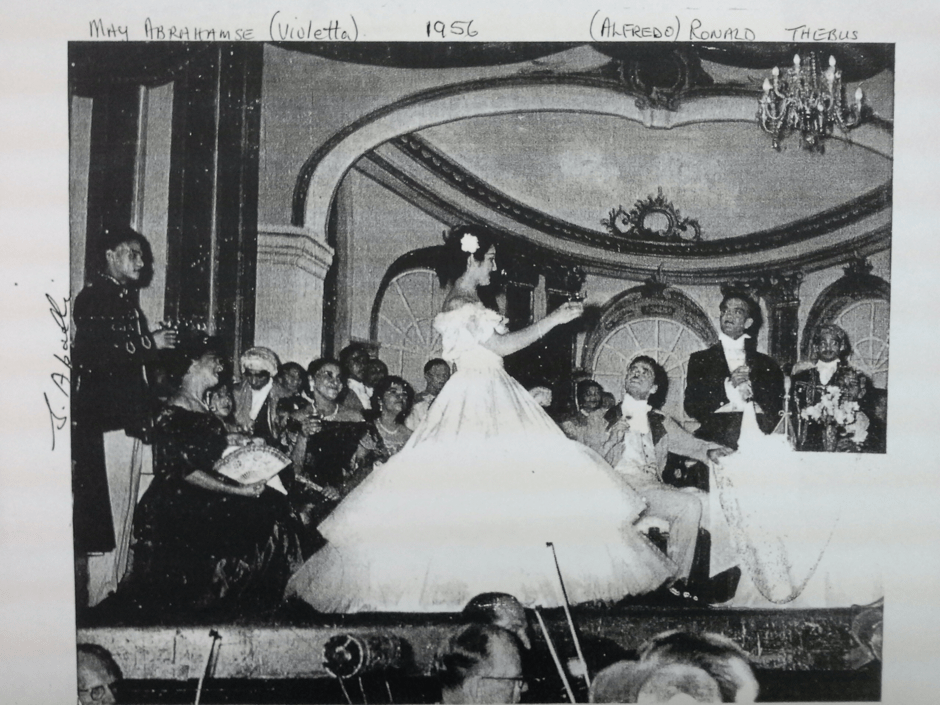

The Eoan Group focused on the cultural and social wellbeing of its members. It offered classes in elocution and deportment, and later incorporated dance and drama training, choral singing, and various forms of physical education. Under the guidance of choral director Joseph Manca, the group began to perform Italian opera in 1956. Between 1956 and 1976, Eoan presented elaborate performances of works by composers including Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, Ruggero Leoncavallo and Pietro Mascagni. Their productions received great acclaim, especially from white critics and audience members who marvelled at non-white performers’ ability to master a European musical form. The group’s claim to fame was that it performed opera ‘as it is done at La Scala’, Italy’s most famous opera house. But Eoan received funding from the apartheid government in order to mount their productions. In return, they agreed to perform for segregated audiences. As a result, they became part of the apartheid regime’s cultural propaganda machine, their actions ultimately serving as a tacit endorsement of the policy of ‘separate development’.

Picture 1: The cover of a production programme for La Traviata, under the distinguished patronage of The Honourable Marais Viljoen, Minister of Coloured Affairs, 14 March 1967. Eoan Group Archive, box 61. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Eoan Group Trust

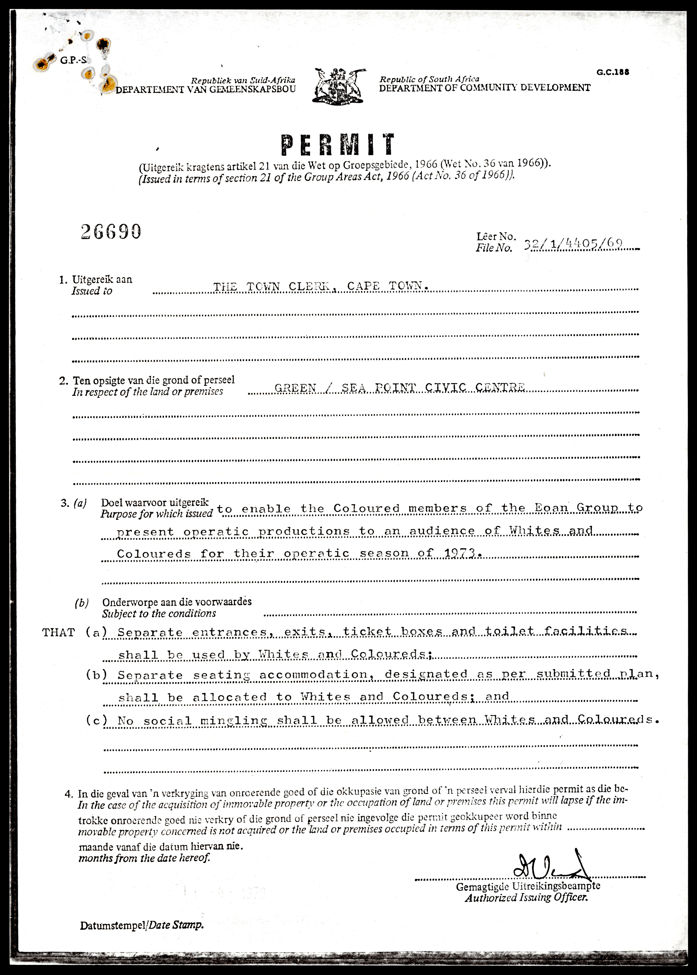

Eoan’s activities increasingly attracted criticism for their apparent complicity in the politics of apartheid. But the group’s performances also allowed its members a form of cultural expression and empowerment denied many of their racial counterparts. Under the guise of cooperation, the Eoan singers claimed for themselves opportunities and a sense of artistic accomplishment.

Picture 2: As part of their operatic activities, Eoan’s members were granted permits to perform in venues normally reserved for white South Africans. This is a permit issued by Cape Town’s municipality in 1973, which granted the group permission to present an opera season in the Green and Sea Point Civic Centre. Eoan Group Archive, box 16, folder 114. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Eoan Group Trust.

In my article I look at how Eoan’s first opera, a production of Verdi’s La Traviata, played with the racialised politics of musical accomplishment in apartheid South Africa. I focus especially on the material trappings of their production, and how they created an imagined world of white splendour at odds with the oppressive realities of coloured life under the regime. This work forms part of a larger project in which I attempt to come to terms with those South African lives that fall outside the narrative troughs of solidarity and compromise, but which remain nonetheless circumscribed by the political moment in which they played out.

Picture 3: May Abrahamse (Violetta) and Ronald Thebus (Alfredo) in the Eoan Group’s 1956 production of La Traviata (1956). Eoan Group Archive, box 101, folder 772j. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Eoan Group Trust.

Eoan represents an important but neglected aspect of apartheid life: the unheroic lives of those who did not participate in grand battles, but rather used whatever means they could to forge meaningful lives under a system that denied their humanity. These small histories form a crucial part of the political struggles that characterise oppressive regimes. Until now, such ambiguous historical narratives have been neglected in favour of the spectacular battles between those regarded as straightforwardly good or bad. In contrast, South African cultural historian Njabulo Ndebele advocates for a ‘politics of the ordinary’: a political discourse grounded in people’s daily struggles for survival and humanity under apartheid’s oppressive regime. He argues that ‘the ordinary day-to-day lives of people should be the direct focus of political interest because they constitute the very content of the struggle, for the struggle involves people not abstractions’.[1]

The Eoan Group sought for themselves an aesthetic world in which apartheid’s realities temporarily faded away. Thus, they could imagine a sphere neither constructed by, nor productive of apartheid’s categories of spectacular conquest, abject domination, feeble collusion, or heroic resistance. The group’s politics of the ordinary produced an alternate reality that played out in counterpoint to the regime with which it seemed to be complicit. They showed that quotidian lives, simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary, have the potential to enact a mode of being the politicisation of which is produced in its very refusal to be co-opted into the strictures of conventional political thought. This is not a disavowal of political responsibility; instead, it is a renunciation of the terms in which such agency is allowed to be articulated.

This piece accompanies Juliana M. Pistorius’ article “Inhabiting Whiteness: The Eoan Group La traviata, 1956” published in Volume 31 Issue 1 of Cambridge Opera Journal, which was recently awarded the 2021 Kurt Weill Prize. Read the full article for free on Cambridge Core now.

[1] Njabulo Ndebele, ‘The Rediscovery of the Ordinary: Some New Writings in South Africa’, in Rediscovery of the Ordinary: Essays on South African Literature and Culture, Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2006 [1991], 41-59, 57.