Are populists sore losers?

Donald Trump still claims the election he lost was unfair and rigged. Other populist leaders have equally proven to be sore losers in the contexts of elections and referendums. But what about populist citizens? In this blog post, Hannah Werner and Kristof Jacobs expand on their recent article from the British Journal of Political Science.

Generally, populist citizens appear to be dissatisfied with the way politics works in established democracies – one reason why this subgroup of the population causes concern to scholars and practitioners alike. It seems plausible that these citizens are also less likely to accept the outcomes of political decision-making if they counter their policy preferences.

Populist citizens and outcome acceptance of a referendum

In our Open Access paper in the British Journal of Political Science (BJPolS) we studied how populist citizens react to loss in the context of a real life referendum (the 2018 Dutch referendum on the Intelligence and Security Services Act 2017). The referendum is a particularly interesting context because populist citizens express support for this type of decision-making in surveys. But does this support reflect a principled desire for different ways to organize democracy or rather an instrumental preference that depends on the favorability of the referendum outcome? Previous research on process preferences shows that citizens can support direct democratic decision-making for both reasons, principled and instrumental.

Given the behavior of populist leaders, we assumed that populist citizens would support referendums primarily because they expect to win them and reject the process and the decision when the outcome does not go their way. In short, we expected populist citizens to be sore losers. We collected survey data using the LISS panel before and after the referendum to test our expectations.

Populist citizens: less instrumental and no sore losers

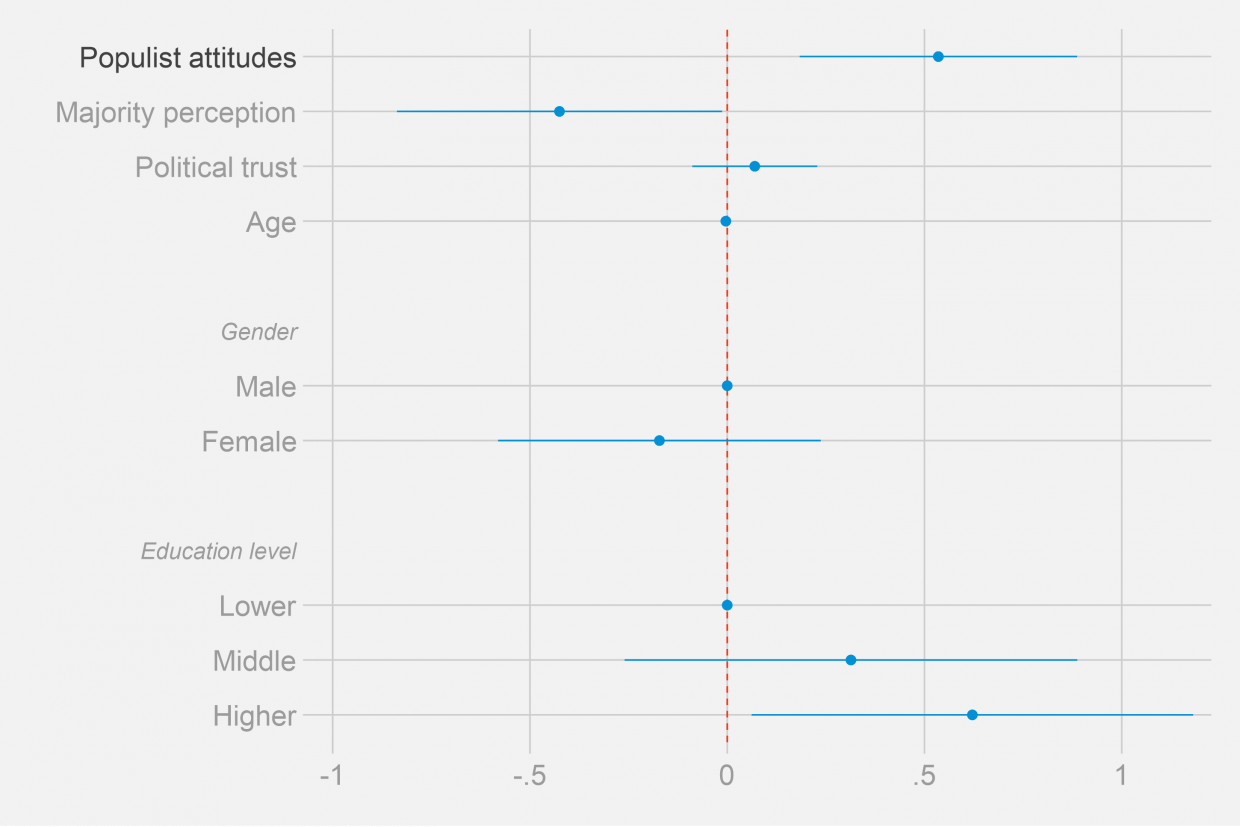

What did we find? To our surprise, populist citizens appeared to be less instrumental in their attitudes towards the referendum and its outcome than non-populist citizens. Their support for holding the referendum in the first place depended slightly less on their desire to change the existing law than for non-populist citizens. Importantly, among the decision losers populist citizens were more willing to accept the outcome of the referendum than non-populist citizens (see figure 1). Populist citizens were the better losers.

Figure 1. The effect of populist attitudes on the willingness to accept the referendum outcome among decision losers

Populist citizens seem to support referendums for normative reasons

These results suggest that populist citizens – unlike some populist leaders – are not necessarily up for ignoring the rules of the game; they just think there should be different rules. In particular, it seems that populist citizens hold a normative preference for decision-making via referendums and consider it a (more) legitimate way of taking democratic decisions than the status quo of representative politics. Many critics worry that participatory processes will only appeal to those citizens who are already politically privileged and engaged – the interested, trusting and educated citizens – and will cause even more frustration among those who feel excluded and neglected. Yet our results indicate that populist citizens, which are often dissatisfied and alienated from existing political structures, appreciate this type of direct involvement even when the results do not go their way.

Clearly, this study only looks at one case and hence multiple factors could affect these results in other cases, most importantly the behavior of political elites before and after the referendum. Yet, it nonetheless provides novel – and somewhat surprising- insights into populist citizens attitudes towards democratic decision making and procedural reform.

Disclaimers and definitions

We define populism in the ideational tradition: the belief that society is divided in two groups, namely the corrupt elite and the good people and that politics should follow a majoritarian implementation of the volonté générale. Importantly, we studied citizens with populist attitudes and not voters of populist parties. Even though there is considerable overlap between these groups, many citizens with populist attitudes vote for non-populist parties and vice versa.

– Hannah Werner, KU Leuven

– Kristof Jacobs, Radboud University

Werner and Jacobs’ BJPolS article is available here.

And you can also watch a video summary of their article.

A Dutch version of the authors’ blog post can be accessed here.