Kind hearts and colonists? Italian military culture and imperialism before the First World War

This accompanies Vanda Wilcox’s Historical Journal article Imperial Thinking and Colonial Combat in the Early Twentieth-Century Italian Army

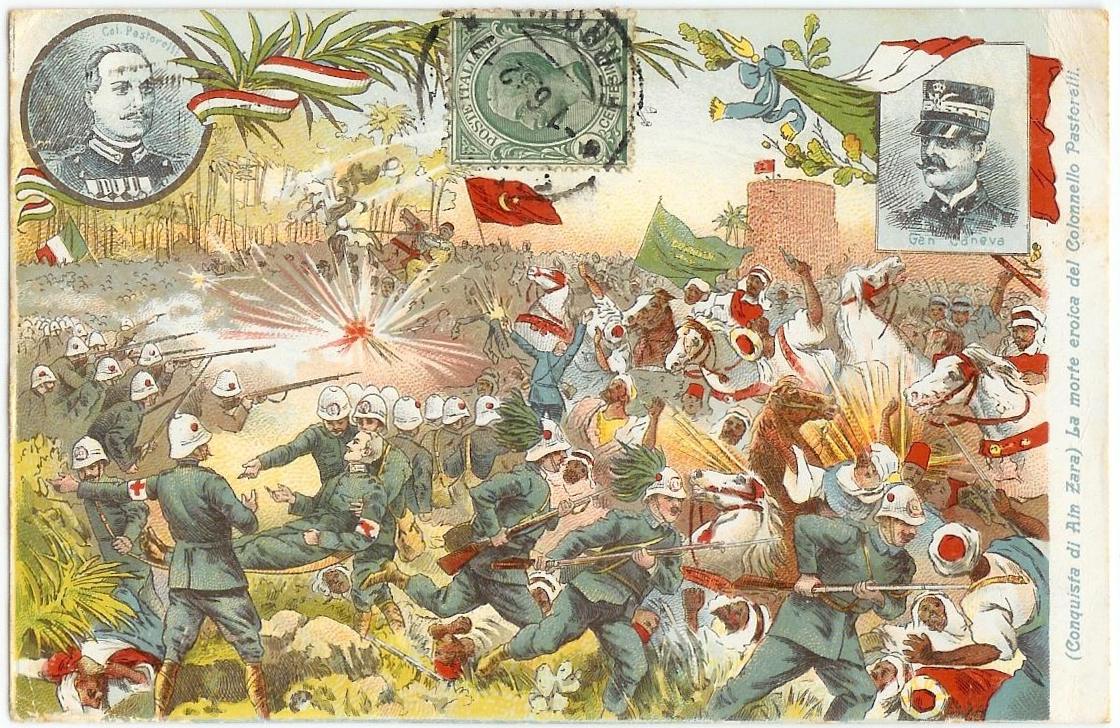

In 1964 the Italian neo-realist director Giuseppe De Sanctis released a bleak Second World War film entitled Italiani, Brava Gente, which translates roughly as ‘Italians, nice people’. The title came from a phrase describing the supposedly mild and compassionate conduct of Italian soldiers during the war. The ‘myth of the Good Italian’, as it is sometimes translated, was a consoling set of beliefs for Italian citizens, a way to free themselves from collective guilt for wartime atrocities. But the image of italiani brava gente long precedes the Second World War, and originated during Italy’s late arrival on the colonial scene in the late 19th century. The newly unified kingdom of Italy sought both an overseas empire and a distinct colonial culture of its own. Colonies were seized in East and North Africa between the 1880s and 1912; the narrative of italiani brava gente helped to frame a distinctively Italian take on the supposed civilizing mission. Italian colonizers were presented as more kind-hearted and benevolent than French or British colonizers; some Italians apparently believed that in the unlikely circumstance of African peoples being given a choice in the matter, they would choose to be ruled by Italy rather than any other European state.

An army’s internal culture determines the qualities of its officers, shapes its doctrine and ultimately strongly influences its performance on the battlefield. All armies rely on traditions and myths to create cohesion and boost morale: so how did the idea of italiani brava gente influence the Italian army, and what other assumptions did it rely on during the pre-fascist period of imperial expansion? During the first half century of the Regio Esercito’s existence it saw more colonial action than any other kind, and its mentality and outlook grew increasingly imperialist, even while its operational doctrine and structure remained that of a strictly national army. But the Italian army faced a serious problem in creating its colonial myth: in 1896, it had earned the unwanted distinction of being the first European army comprehensively defeated in war by an African enemy. The army was profoundly humiliated by the defeat at Adwa by the Ethiopian Empire, and terribly afraid it might happen again. In the years after 1896, what I call ‘Adwa Syndrome’ developed: Italian officers were deeply suspicious of all current or potential African and Arab subject peoples, who they considered inherently untrustworthy, savage and prone to vicious betrayal. This anxiety was actually compounded by the myth of italiani brava gente: if Italians were ‘too kindly’, this might encourage colonial enemies to think they could take advantage of Italians’ supposed good nature. Together, these ideas had the toxic effect of encouraging brutality and justifying atrocities. It’s sometimes assumed that colonial war crimes were the product of fascism, but I discuss some atrocities of the Liberal era and the military culture that helped to produce them.

Vanda Wilcox, Imperial Thinking and Colonial Combat in the Early Twentieth-Century Italian Army, The Historical Journal