‘Down pythons’ throats we thrust live goats’: snakes, zoos and animal welfare in nineteenth-century Britain

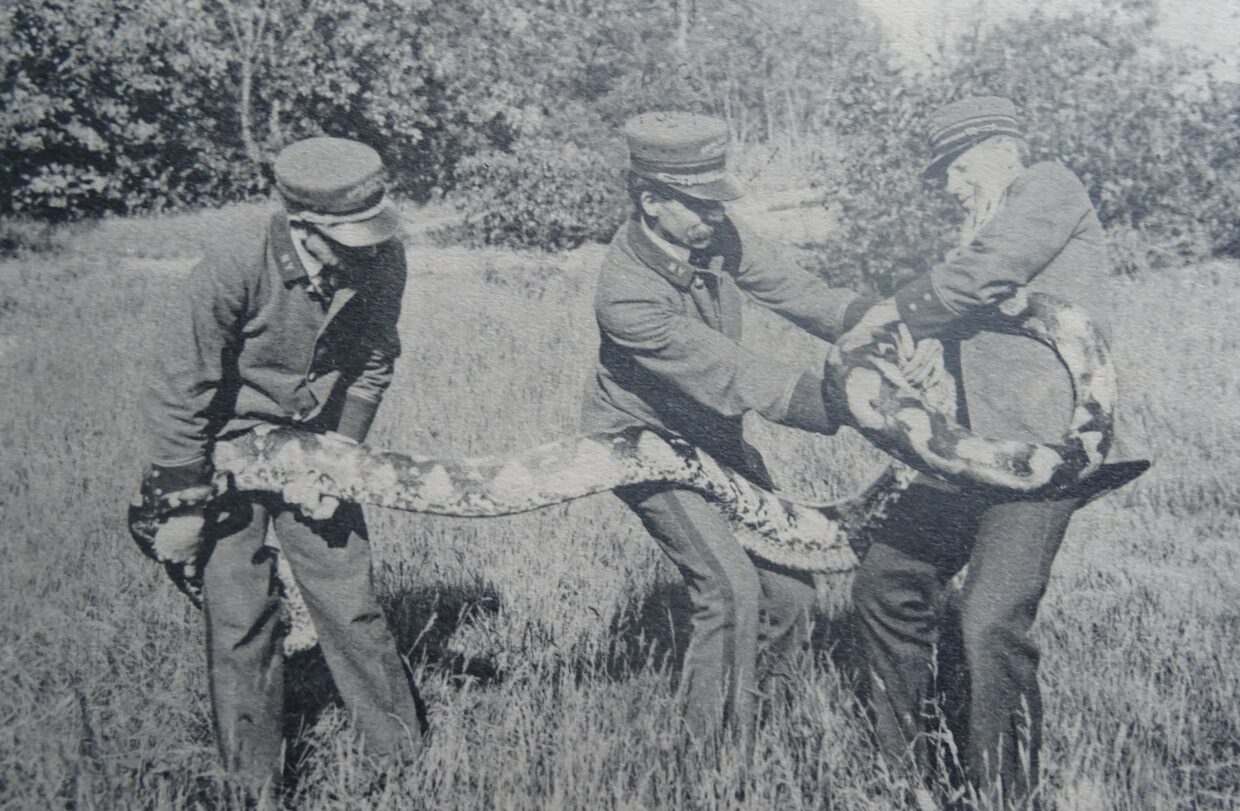

In September 1902, as he was passing the Reptile House at London Zoo, T.W. Hitchmough was approached by a ‘small goat of friendly disposition’, which came running up to the wire fencing of its enclosure, eager to be ‘petted’. While Hitchmough was busy ‘scratch[ing] the little fellow’s head’ a keeper passed by, and Hitchmough asked him ‘What are these chaps kept here for?’ The keeper proceeded to tell him that ‘the big python gets them’, that he killed them himself, and that it was not a quick death, for ‘[t]he python hasn’t much room to move about, so perhaps he only gets one coil round, and that grip forces out the entrails and breaks the goat’s ribs’. This statement shocked Hitchmough, who, after steadying his nerves with a ‘drop of brandy’, addressed a strongly-worded letter to the Free Lance magazine exhorting readers to ‘help stop what seems to me to be wanton cruelty in the Zoological Gardens’.[1]

Hitchmough’s letter sparked a heated debate in the press about the ethics of feeding captive snakes on live prey. Was it right to feed pythons and boa constrictors on warm-blooded goats, pigeons and guinea pigs? Did snakes require their dinner to be alive when they ate it, or could they subsist on dead (or at least, recently killed) prey? Did the unnatural conditions imposed by captivity render the suffering of the prey animals more acute? Did goats, ducks and rabbits experience fear when put into the snakes’ enclosure, or were they blissfully unaware of their likely fate? Who was best qualified to answer these challenging biological and moral questions: zoo professionals or animal protection advocates?

In a new article in the British Journal for the History of Science, I unpick some of the competing arguments put forward for and against live feeding and trace the evolution of the practice from the 1860s to the 1910s. In the big scheme of things, of course, the feeding of snakes with live prey was a very niche issue; far more animal lives were sacrificed in Victorian Britain to fill human stomachs, clothe human bodies and advance human understandings of disease. I argue, however, that the live-feeding debate attracted disproportionate attention from contemporaries because it forced participants to weigh the relative rights of different species (in this case, pythons and goats) and to reflect on competing criteria for moral consideration. I suggest that live feeding served as a proxy for other more widespread abuses, from vivisection (which also entailed protracted suffering) to canned hunting (which denied prey animals the chance to escape). As one critic of the practice remarked: ‘Slaughter-house torture is brief and tolerable compared to [live feeding], which is as repugnant as vivisection’.[2]

Today snakes are no longer fed on live birds and mammals (at least in Britain), though the feeding of live invertebrates to zoo animals is permitted.[3] The ethical questions raised by the live feeding controversy remain relevant, however, and continue to shape our treatment of other species. Testing drugs on rats, for instance, is generally deemed more acceptable than testing them on chimpanzees, while exterminating ‘invasive’ cane toads raises fewer moral qualms than culling ‘invasive’ grey squirrels. Trophy hunting elicits revulsion because the animals earmarked for culling are often tame (like the goat petted by Hitchmough), and their death sometimes protracted; the famous lion, Cecil, shot by an American dentist in 2015, reportedly took 11 hours to die.[4] While the furore over live feeding may have abated, therefore, debates over animal welfare remain very much alive and are framed by some of the same concerns that troubled Victorian animal protectionists.

Snakes, it turns out, are good to think with.

[1] ‘Cruelty at the zoo’, The Humanitarian, October 1902, p.63.

[2] ‘Serpents and Serpent Feeding III’, The Animal World, April 1881, p.50.

[3] Geoff Hosey, Vicky Melfi and Sheila Pankhurst, Zoo Animals: Behaviour, Management and Welfare, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp.434-5.

[4] Jani Hill, ‘Cecil the Lion Died Amid Controversy—Here’s What’s Happened Since’, National Geographic, 15 October 2018.

‘Down pythons’ throats we thrust live goats’: snakes, zoos and animal welfare in nineteenth-century Britain by Helen Cowie.