On the trail of a dangerous heart and lung worm; diagnosing A. vasorum in dogs

The latest Paper of the Month from Parasitology is ‘Comparison of coprological, immunological and molecular methods for the detection of dogs infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum before and after anthelmintic treatment‘. In this blog Dr Manuela Schnyder discusses the paper in more detail.

“A dog and fox parasite which was originally discovered in France (and therefore also called the French heartworm) is conquering wide areas within Europe as well as being present in single spots of North America: its name is Angiostrongylus vasorum.

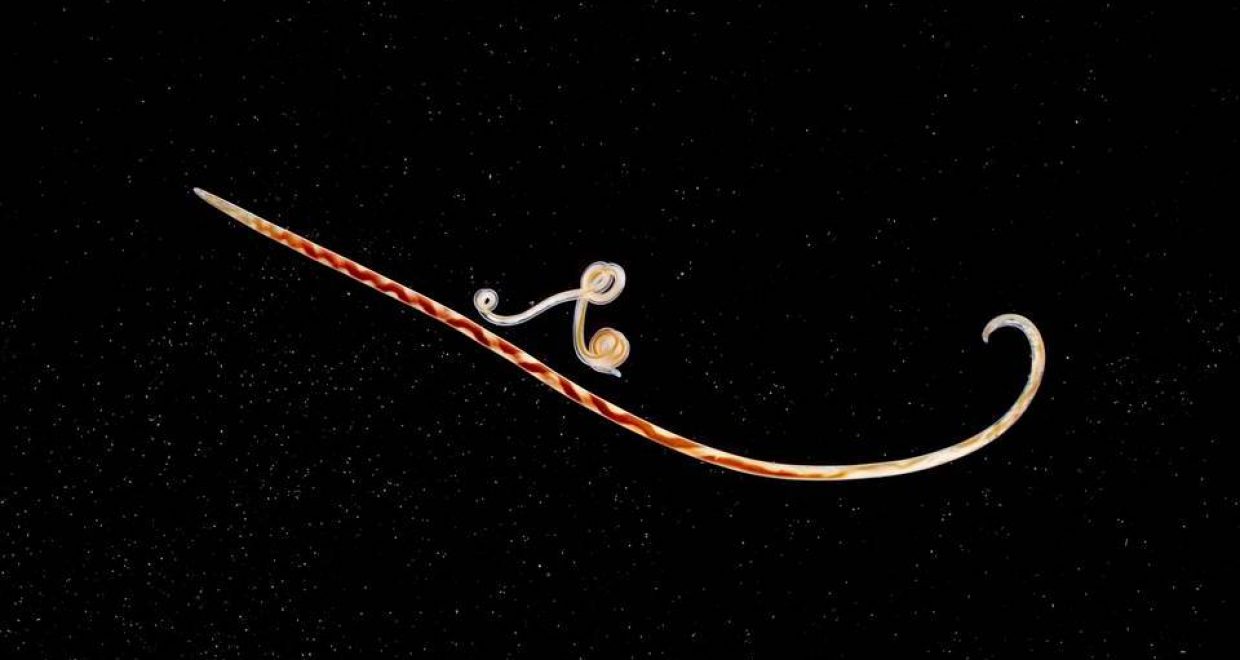

Video depicts A. vasorum at first stage larvae. Curtesy of Dr Manuela Schnyder.

Canine angiostrongylosis can be fatal. Dogs affected by A. vasorum may present with a wide range of symptoms making the clinical diagnosis of canine angiostrongylosis challenging. When the eggs and larval stages are in the lungs, verminous pneumonia and corresponding respiratory problems are the most common signs. The infected animal can also suffer from bleeding from varying body parts, neurological deficiencies as well as other nonspecific symptoms.

On the other hand, once the infection is identified, the treatment is very simple, consisting of the administration of an appropriate anthelmintic.

Veterinarians and parasitologists are doing their best to further describe clinical manifestations and clarify the epidemiology of this parasite which includes a two-host life cycle with snails and slugs acting as intermediate host, and investigate the multifaceted pathogenesis of this fascinating parasite. The earlier affected animals are diagnosed the better as damage to the tissues starts very early at the migrating larval stages, and the more advanced the infection, the more likely it is that non-reversible pathologies will develop.

Different approaches for diagnosing A. vasorum in dogs are possible. Parasitic stages can be classically detected by faecal analysis. We alternatively developed serological tests, one for the detection of circulating antigens, one for the detection of specific antibodies against the parasite. Both demonstrated of great value for epidemiological studies. In addition PCR performed with different materials such as blood, faeces or sputum (all potentially harbouring stages of A. vasorum and therefore parasitic DNA) is also possible. With all these diagnostic options, one needs to know how good they are and most notably at which moment of the infection they can be useful. This is why we compared all mentioned methods, based on samples from known infected animals, collected over time. We additionally tracked dogs after anthelmintic treatment, in order to know at which moment the tests result negative: this information allows vets and dog owners to determine if treatment was successful.

It is nevertheless evident that disease awareness is crucial: the best diagnostic tools are useless if animal owners and vets do not even consider a parasite bearing the blame for coughing, nose bleeding or maybe just fatigue in a dog. I unfortunately can confirm that we are regularly contacted by the Pathology Unit identifying dead infected dogs, in order to check how many worms can be retrieved from heart and lungs of an animal in which evidently the infection has not been diagnosed on time.

There are many open questions in the biology of this intriguing parasite: How and where do dogs ingest the infectious stages? How can we know how heavily a dog is infected? Why do some dogs develop blood clots and others not? And many others. Accurate diagnostic tests are also the mainstay of epidemiological studies, and it is hoped that our results further support efforts to understand factors driving the distribution and transmission of A. vasorum in its expanding global range.

While researchers address these questions, the comparison between different diagnostic tools presented in our paper should help clinicians to adopt the most appropriate procedures against this dangerous parasite of dogs.”

The article is freely available here until 6 September 2015.

Main image: Dog diagnosed with angiostrongylosis curtesy of Dr Manuela Schnyder.