Pursuing the prayerstone hypothesis

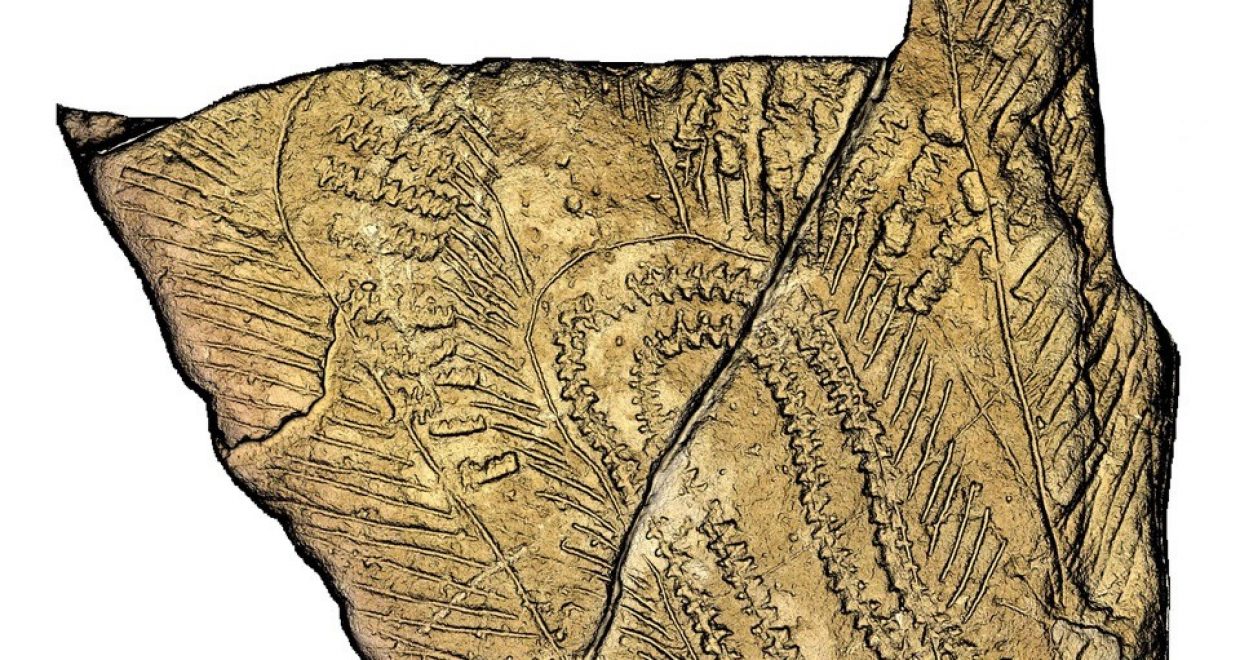

Incised stones have long attracted my attention because of the large assemblage (more than 400) that we excavated at Gatecliff Shelter. My interest was recently re-awakened after learning of Southern Paiute oral histories about the use of incised stones as prayerstones, and I reached out to indigenous colleagues in the Great Basin.

I decided to pursue the prayerstone hypothesis for several reasons. The first was to transcend and augment the predominantly “gastric” paradigms that have dominated Great Basin anthropology since the days of Julian Steward. I’m not opposed to such approaches at all, but do believe they need to be supplemented by alternative views, especially those including communities of practice and more cosmological perspectives.

Although a couple of my archaeology friends warned that the idea of “prayerstone” could never be addressed “scientifically,” I don’t agree and that’s why I wrote the American Antiquity piece. That’s also why I’m finalizing a book-length analysis of the 3500 incised stones now documented from the Intermountain West—in part to demonstrate that just because the prayerstone hypothesis originated in Indian Country doesn’t automatically make this study “unscientific.”

Prayerstone research also synchs with my overall feeling about questioning conventional wisdom and orthodoxy. The Numic Spread hypothesis has dominated Great Basin archaeology for decades, and if we did science by democracy, would win the election hands down. But to me, when everyone thinks alike, nobody’s thinking very much. I vastly prefer entertaining multiple working hypotheses whenever possible—and the prayerstone project seemed a good way to do this.

I also like the potential of making archaeology a little more responsible to indigenous stakeholders. Since the passage of NAGPRA, Numic-speaking people have sometimes been locked out of part of their own past because so many tribes were dismissed as recent arrivals. Along with the most recent ancient DNA results, the prayerstone hypothesis would suggest that science-based archaeology does indeed have potential for questioning the dominant narrative and, just perhaps, could help open a door or two in Indian Country.

David Hurst Thomas is the curator of North American Archaeology in the Division of Anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History and a professor at Richard Gilder Graduate School. His full article, published in the January 2019 issue of American Antiquity, is currently free to access for 30 days.