Unpacking the Political Implications of Latinx Interstate Migration

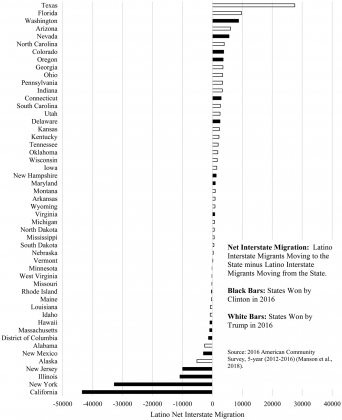

Among the many narratives about political ramifications of racial and ethnic demographic change in the United States over the last several decades, the potential of Latinx population growth to shift the nature of politics in the states, and even the calculus of Presidential campaigns, gained prominence as Latinx population growth seemed concentrated in what were long considered Republican strongholds. While rates of growth tailed-off in the latter half of the previous decade as immigration reached its lowest levels in decades, Latinx interstate migration patterns demonstrate that Latinos continued to move to these conservative states and away from more liberal states—a phenomenon highlighted in a Figure I constructed for a study recently published in the Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics displaying the net Latinx interstate migration by state from 2012 to 2016.

Many of those Latinx destination states, such as Texas, Florida, Arizona and North Carolina also stand to gain at least one congressional seat through reapportionment following the 2020 Census and subsequently an additional Electoral College vote. Brookings’ demographer, William H. Frey notes that while on its face, more power in Red states helps Republicans, “…a good part of recent population growth in Texas, Florida, Arizona, and North Carolina should continue to be from the Democratic-leaning voting blocs of Latinos or Hispanics, African Americans, and Asian Americans, as well as white college graduates moving from blue states such as California and New York. Thus, it is difficult to predict the decade-long political ramifications of the 2020 census’s congressional reapportionment.”

Two important empirical points arise from Frey’s statement. First, that movers of color will uniformly bring Democratic votes to new destination states. Second, that others bring their politics with them. The latter is fairly well-established, but not without debate in the literature on inter-state migrant political behavior as adaptation and homophily (selecting destination states based on compatibility with established political orientations) may result in new migrants that closely reflect their destination state’s politics. The former has simply not been tested adequately, but holds profound importance if reflective of reality. If people of color uniformly bring left-leaning views to new states, then destination state politics ought to shift to the left, if not in the short term, over a decade as migrants become established voters. But what if people of color bring the politics of their origination state to destination states? And, more specifically, what if Latinos, whose growth in new destination states from the Deep South to the Rust Belt lies at the heart of much of the story of the nation’s demographic shift, bring their politics with them as they move across state lines?

These questions motivated my study, entitled “Pack your Politics! Assessing the Vote Choice of Latino Interstate Migrants,” which employs data from the 2016 Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Study to examine whether Latinx interstate migrants tend to bring the politics of their departure states with them. It turns out they do.

Using several measures of the political context of Latinx interstate migrant’s departure states as a key independent variables, and comparing these migrants 2016 voting preferences in both Presidential and Congressional elections to the preferences of current residents within a state, the analyses revealed that Latinx movers tend to pack their politics when moving across state lines and actually vary quite a bit in their voting preferences depending on which state they came from.

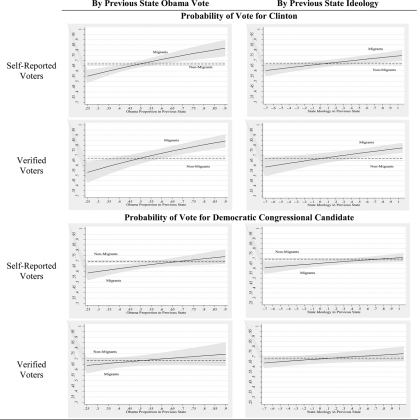

Latinos from states like Texas were more conservative than Latinos from states like California. And, depending on the destination state’s political orientation, tended to be more liberal or conservative than destination states’ native Latinx populations. The figure below illustrates the magnitude of the variation in support for Clinton (top panels) and the Democratic Congressional Candidate (bottom panels) across the range of two indicators of departure state liberalism. While much more pronounced in Presidential choice, Latinx interstate migrants arriving from more liberal states tended to support Democratic candidates in 2016 at significantly higher rates than those departing more conservative states. In short, we ought not treat all Latinx migrants as unified voting bloc. The effect of Latinx interstate migration on destination states will depend to some extent on which state the migration flows originate.

Estimated Probability of Voting for Clinton and the Democratic Congressional Candidate by Previous State’s Political Context

Note: Solid lines and gray areas present the estimated probability of voting for the candidate and 95% confidence intervals, respectively, for interstate migrants over the in-sample range of the previous state’s political context. Dashed lines and the area between the dotted lines present the estimated probability of voting for the candidate and 95% confidence intervals, respectively, holding the value of the previous state’s context at zero. All other values are held at observed values for each respondent in the sample. Estimated from models reported in Table 3 (Vote for Clinton) and Table 4 (Vote for Democratic Congressional Candidate.)

That said, and comporting with Frey’s conjectures, we should generally expect that Latinx interstate migration will introduce more Democratic orientations to destination states. While Latinx movers from conservative states such as Texas are more conservative than Latinx natives in liberal states like Massachusetts, this study shows that Latinx movers are still going to be more liberal than most statewide electorates. Moreover, a ton of good research suggests that whites react to Latinx migration flows by moving to the right…a move that may offset any gains for Democrats—particularly if Latinx movers pack their politics and bring a political orientation that is more reflective of the conservative state’s from which they move.

Robert Preuhs, Metropolitan State University of Denver

This blog is based upon the authors’ article in the latest issue of the Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics which you can read free of charge until the end of April 2020.