Why remember the fifth of November?

This accompanies Philip Williamson and Natalie Mears’ Historical Journal article James I and Gunpowder Treason Day

The 5th of November is familiar as a traditional day of festivities in England, marking the anniversary of the discovery of the Gunpowder plot in 1605. The annual celebration survives as the distinctly secular ‘Guy Fawkes day’ or ‘Bonfire night’, but it began and remained until 1859 as an official day for religious thanksgiving, generally known as Gunpowder treason day. Historians has always assumed that this commemoration was created by an act of parliament in 1606. But the chance discovery of a crucial document in the Tanner manuscripts in the Bodleian Library led to research which has revealed a different and earlier origin. The thanksgivings were actually initiated by King James I during November 1605, two months before the introduction of the parliamentary act, in an order communicated by the archbishop of Canterbury to every parish, cathedral and chapel in England and Wales. This order is significant for two reasons. It states the king’s own understanding of the reasons for thanksgiving, and it turns the parliamentary act into a historical puzzle: why was it passed, when an annual commemoration had already been ordered?

Recognition of new evidence for such a well-studied episode as the Gunpowder plot is rare. Our article contains a transcription of the king’s lengthy order, together with an even earlier order for the first publication of the liturgy which was used for the annual services. It shows that the king did not share the interpretation of the Gunpowder plot and the purposes of thanksgiving which were propounded by parliament and by generations of English preachers and writers – as an instance of God’s special favour towards England, and as further justification for anti-catholic beliefs and policies.

James was after all Scottish; and as king of Scotland he had earlier survived what he considered to be an assassination plot by a presbyterian family, the ‘Gowrie conspiracy’, an escape for which he had already appointed two sets of annual thanksgivings, originally in Scotland and then in England. For the king, the discovery of the Gunpowder plot was the second of two divine interventions for the same purpose, of preserving himself, the Stuart dynasty and his rule over all his kingdoms. For him, the thanksgivings had a British scope, and accordingly they were ordered or observed in Scotland and Ireland as well as in England and Wales. The Scottish antecedents are explicit in the king’s order, both in relating the Gunpowder plot directly to the Gowrie conspiracy and in a remarkable and previously unknown extension of the new English thanksgivings: these were to be not just annual but weekly, with special sermons and prayers in all churches every Tuesday. James also regarded his two deliverances as being from traitors, irrespective of their religious persuasions – and he tried to prevent the Gunpowder plot from becoming a cause for increased persecution of catholics. The subsequent act of parliament was an outcome of tension over religious policies between the king and ‘godly’ or puritan members of parliament, who were determined to exploit the plot to take further measures against catholic recusants.

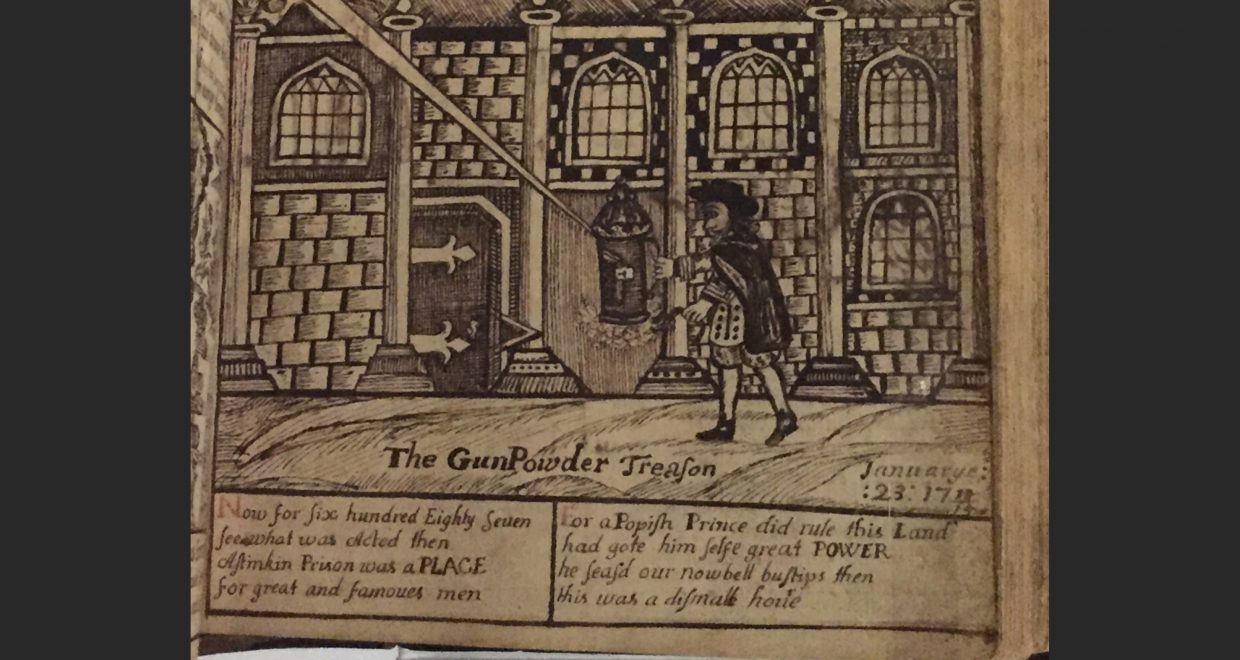

Main image: Page of the Bible composed by Abraham Sheares of Exeter (1710 – 1731) that presents the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605 as a providential victory of Protestants over Catholics. Wikimedia Commons