Experimental Collaborations at the Art-Anthropology Interface

Frederik Unseld is a Ph.D. candidate at the Institute for Social Anthropology at the University of Basel, Switzerland. His Ph.D. focuses on artists in the context of political and economic violence in Kisumu, western Kenya. It is part of the research project ‘Art/Articulation: Art and the Formation of Social Space in African Cities’, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. Email: frederik.unseld@unibas.ch

In anthropology today, collaborations at the interface between anthropology and art are increasing, as the discipline continues its struggle to reinvent itself in the long shadow of the Writing Culture debate. One of the wishes of those arguing for a collaborative convergence between scholar and artist is to make more readily perceptible and intelligible facets of everyday life that do not often feature in mainstream accounts of urban experience. I became entangled in such joint creative processes during my doctoral research on artistic practices in Kenya’s third-largest city, Kisumu, at first, unwittingly. I only gradually grew aware of the changing nature of my relationship with my interlocutors, allowing artistic endeavours to take centre stage in my everyday life as a researcher.

Just as any other Ph.D. student would probably have done, I began my research using the conventional methodologies in the anthropologist’s toolkit: Mapping the actors in question, in my case, young adults inclined to art, and as familiarity increased, observing and participating in this particular peer group’s activities. However, time and again, the involvement with artists from various genres (dance, music, social media, “artivism”) pushed me towards a more collaborative stance. For instance, I was invited to join the organizing committee of an activist initiative that held marches through the city to address election-related violence. Kisumu is one of Kenya’s opposition-strongholds and the group’s activities proved contentious so that I was feverishly defining and redefining just how deeply involved I wanted to get. This was especially the case when one of the demonstrations was violently disrupted and members of the committee were overtly threatened over their activities.

For historic and political reasons, national development efforts have neglected the city of Kisumu and low-income settlements surround the city centre like a belt. My laptop and camera became important means of connecting with people during my daily excursions into the shantytowns, accompanied by Kisumu artists. It was easy to take pictures during local fashion shows, or for an artist’s social media feed. Taking pictures in an everyday context in the shanty areas, where the power imbalances at play and the limits of familiarity quickly shifted, was less self-evident. Although at first, I kept my devices out of interactions as much as possible – sensing that they were just another marker of the socio-economic gap between myself and the people I was working with – these devices turned out to be my best allies. I gladly took all the photos and video clips that artists asked me for, whether it was filming a dance choreography for joint critique, supplying free photos of events, or the artist striking an occasional pose during a stroll through the neighbourhood. However, as my research progressed, I found myself concerned that my relationship with the artists as “informants” might not be exactly that expected by classical anthropology. While I continued to record my interlocutors’ life histories and accompanied them on their tours through the low-income settlements, we were spending more and more time chatting about their ideas for music videos, a documentary to be shot, and other such projects that had piqued my curiosity. Gradually, my personal diary notes taken during the day and transcripts of conversations recorded during walks in town all seemed to be taking on a direction of their own, toward a more narrative register of experience.

The two anthropologists Tomás Sánchez Criado and Adolfo Estalella are particularly interested in collaboration as a practice, which occurs in “contexts where anthropologists meet para-ethnographic others”, and where anthropology takes the form of “engaging in joint epistemic explorations with those formally described as informants, now reconfigured as epistemic partners”. Such explorations, they state, “involve experimentation with the vocabularies in use”. I found Criado and Estalella’s invitation somewhat reassuring, as I participated more and more in the production of the very things I was studying. I became particularly interested in the performances and vocabularies of Spoken Word, a vibrant art form in Kenyan cities. My own longstanding involvement with hip hop music in Germany not only provided a basis for discussion with the self-reflective poets in their role as “epistemic partners” but also allowed us to let our hair down, record some music together, and sketch out lyrical ideas – now as creative partners.

Our shared subcultural background provided something of a glue, as our conversations crossed from English to Swahili, to Sheng, and to the poets’ explanations of their poetry in Dholuo, the primary language spoken in Kisumu. The artists’ never-ending flow of ideas, words, and phrases helped me to understand better how people in Kisumu understood the internal dynamics of the urban lifeworld I tried to describe. Their efforts to strike it big (let alone to make-do and put food on the table) were relentless, complex, and highly dynamic, and their art was one way to stylize and narrate these efforts. While living in neighbourhoods with a lack of basic sanitation, rampant gang criminality, and crippling structural-economic violence, the artists were ceaselessly confronted with the images of success and prosperity that circulate on social media in ever-increasing intensity. The systemic neglect by “the powers that be” has created a disruptive everyday life for them that is best described by the oxymoronic notion of an “enduring crisis”. In this context, the artists’ attempts at “making sense” on a signifying level, and of “making sense” in a material sense (as in the neoliberal adage, “if you don’t make money, you don’t make sense”), appeared almost schizophrenic from my own outsider’s perspective.

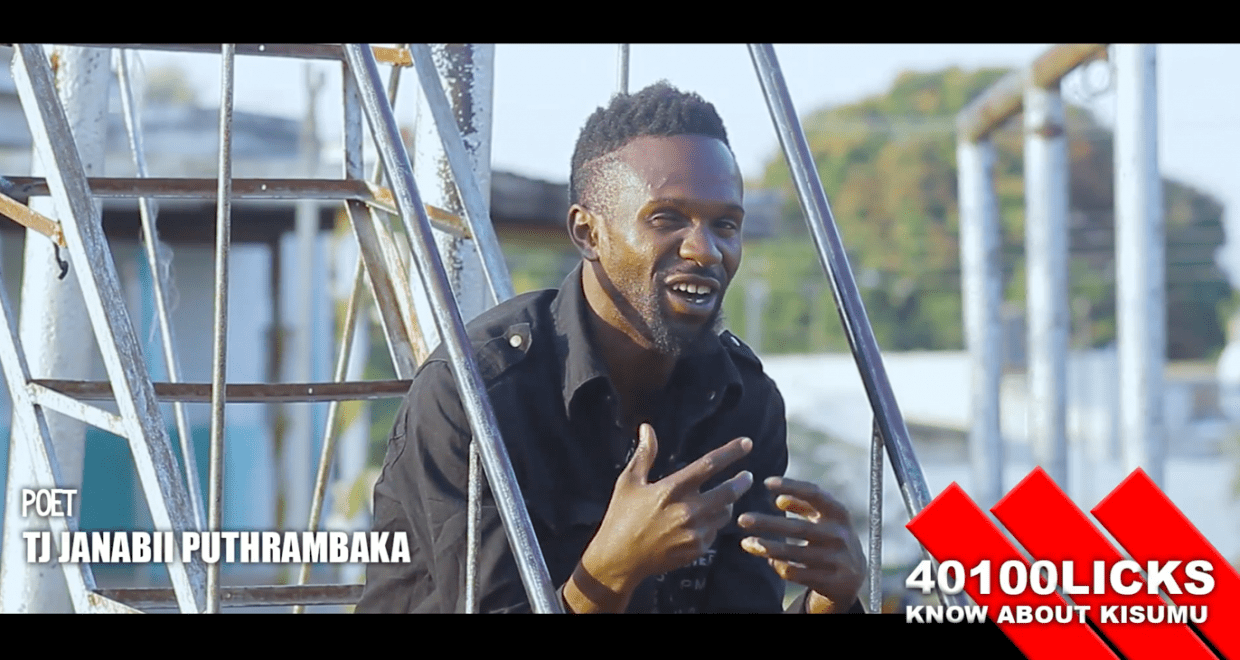

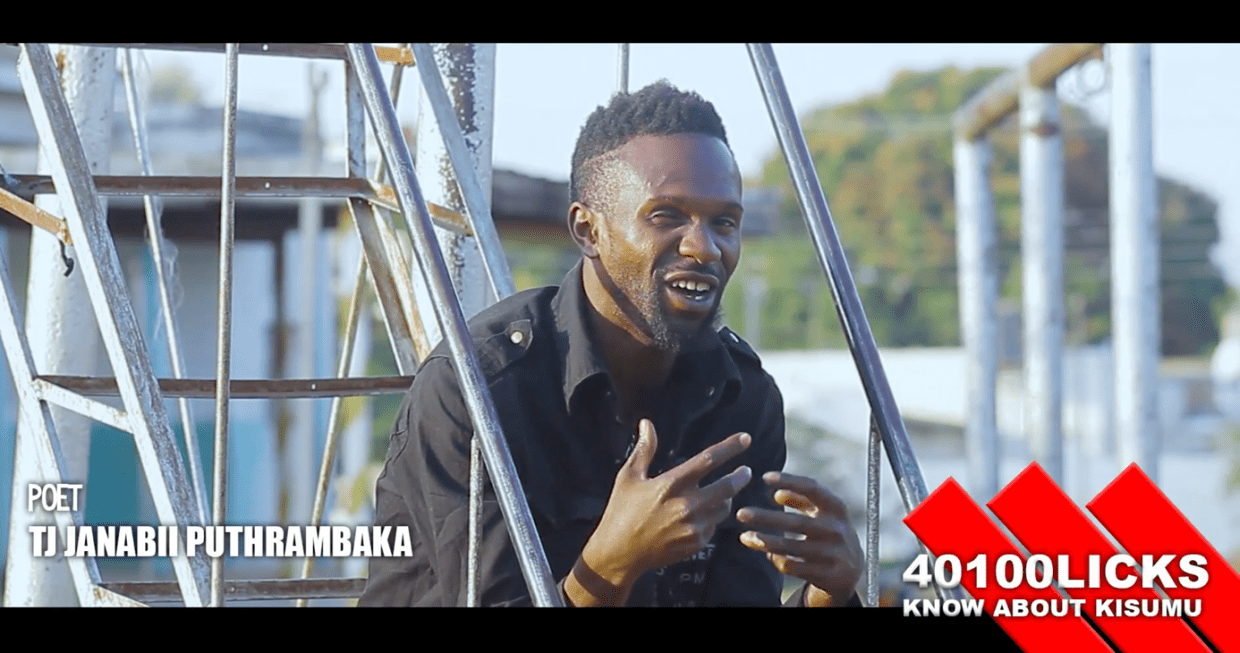

During the last months of my stay, I was invited to a workshop at the British Institute for Eastern Africa organized by a group of activist-scholars. The conference targeted the notion of “hustling”, a term which many Kenyans use to describe their daily efforts to improvise and juggle multiple sources of income in order to survive and secure a certain degree of decency in their lives. This more mundane and tedious dimension of everyday life was exactly what I had attended to in the artists’ lives, as well as in their works, which offer copiously commentary on citizens’ creative efforts to manage with the limited means available to them. Notwithstanding their own critical theoretical advances, the workshop’s organizers, Tatiana Thieme, Meghan E. Ference, and Naomi van Stapele, considered their Kenyan interlocutors whom they had invited to the atmospheric house in Nairobi’s leafy Kileleshwa neighbourhood, to be the real “experts in the room”. One of these experts was Janabii, a poet from Kisumu with whom I had worked. He performed his piece “Broken Glasses”/”Broken CD”, an articulate reflection on the youth’s predicament in Kenyan cities today, and took part in the lively discussion.

The resulting Special Issue of this workshop speaks to the myriad urban practices and positionings through which Kenyan citizens secure the necessities of life, even as they are cut off from mainstream support and infrastructure. In my contribution to this Special Issue, I follow Janabii for one whole week as the poet waits to hear whether he will be invited to take part in a more or less elusive public event. My account of Janabii’s week of waiting for returns, over and over again, wave-like, to passages in his poem. Shifting between accounts of my days in the artist’s company and a line-by-line reflection on the poem, a rhythmic structure emerges for analysis. This structure, in turn, functions as an echo chamber: It stands as a counterpart to – or a reflection of – the rhythm of Janabii’s life. In his piece, Janabii declares, “I speak off-key and off-beat”. In my account of his way of life, I trace the fleeting moments when free from the constraints of rules and language, Janabii constitutes his own rhythm and melody, his own sequence of incidental notes, events, and pulses.

The back-and-forth between Janabii’s participation in city life – hustling – and his poetic reflections of the same shows how composing, rehearsing, and performing his poetry allow him to bring structure to a life characterized by mostly unwanted inactivity. Hour upon hour and day upon day spent waiting for something, anything, to happen, find rhythm in the act of reflecting on, talking about, and making art. This observation not only applies to Janabii but, more broadly, to all of the artists with whom I worked in Kisumu. Their lives and works speak richly to the subject of waiting, as it is addressed in numerous essays by AbdouMaliq Simone. Simone’s reflections on city life, as experienced by young men in contexts of mass unemployment, were also echoed in the recurrent observation that even when nothing seems to be happening, the practice of preparing to make art or, in other words, the waiting time leading up to it, is creative time; creative not so much of art per se, but as an art of living, as captured in the German word Lebenskunst.

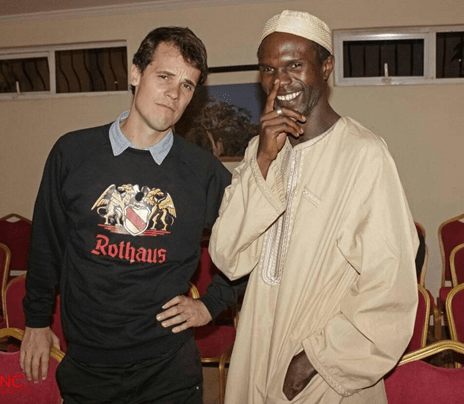

The anthropologist/author with the artist, Janabii, at “Beyond the Stereotype”, Sovereign Hotel, Kisumu, 2017.

Explore the special issue, and enjoy freely available articles for a limited time from the journal, Africa here.