Reflections on Directing My First Field Project: Safety, Logistics, and Preparation

Those of you who were born in the late 80s/early 90s may remember the movie “The Princess Diaries.” Remember the scene where Mia has a rough day, wants to cry, gets in her Mustang, the top won’t go up, and then it starts pouring while she sits drenched and dejected in her open convertible? Let me tell you the archaeology version.

It started when I set the camera bag on land that, unbeknownst to me, had recently been claimed by some red ants. They hadn’t built their hill yet, so they decided the camera strap was a good place to hang out until the camera bag was moved and they could begin their work. They were content to chill until I put the camera (and strap) to my face to take a picture of a feature that the crew was documenting. Thus my first piece of advice to those of you directing field projects is: always check your camera (and camera strap) for ants. I don’t know if any of you have had red ants crawl up the inside of your nose, biting as they go along, but if you are looking for a new way to torture your enemies, I can vouch for its effectiveness.

Thankfully, it was at the end of the day. I (painfully) breathed a sigh of relief as we began loading the gear in the truck after the hike out of the site, until one of the crew members noticed that the boring tip of the soil corer (which was necessary for breaking through the rocky sediments to obtain our samples–the main focus of our project) was missing; it must have come off on the hike back. Thus the field day was lengthened by about an hour and a half searching (in vain) for the missing part. We were really good at finding earth-colored pottery sherds and flakes left on the ground 500 years ago, but really bad at finding a fairly large, shiny, metal cone that we dropped 10 minutes ago.

With a storm rolling in, I had to call off the search and get the crew back to the house. We got back to the truck (this was one of those “roads” where 4WD is necessary, and is ESSENTIAL if there’s any rain), I engaged the 4WD, and…nothing. Without warning, the 4WD actuator had picked that moment to completely stop working.

And then it rained harder.

*End “Mia crying in her Mustang” scene.*

As you can tell by me writing this, the crew and I survived that day (a rear-wheel drive technically becomes a front-wheel drive if you drive in reverse, and momentum is your friend). I tell you this story because that is the worst thing that happened on the project, and thus I consider the project a success. A five-month field project involving four fairly-remote project sites and a rotating crew of 30 people (including community volunteers from 15-75 years old) finished on schedule and on budget with no crew member injuries and no conflicts.

As I talk with more archaeologists, I learn how, sadly, rare that can be, as well as how little training archaeologists receive in how to plan and direct a field project and manage a diverse group of people with varying needs. My coauthors and I hope that our article, and the Advances in Archaeological Practice Health and Wellness issue in general, can help change that trend. I am so grateful that this project, my first field project as PI, went well and that the crew remained safe. In our article, my coauthors and I outline things we learned and resources we used to help us prepare for directing field projects mindful of crew wellbeing. I hope the resources and tips in that article are helpful to those of you who are also beginning to direct field projects, including students! Here are 5 other tips that helped me prepare for directing my first field project that I hope may help you too:

1. Be a good participant observer. While you are a crew member on different projects, observe and make note of what works well on the project and what doesn’t. Ask to sit in on logistical meetings/planning sessions the directors have during what would be the crews’ free time. These meetings are a great place to learn what goes into managing a project and a workforce.

2. Put (and get) everything in writing, even things you think are common sense. Expectations, schedules, resources, emergency protocols, maps, acknowledgement of risk forms, etc. should all be in straightforward writing and distributed to all project participants. This is important for safety, legal, cohesion, and equity reasons.

3. Routine and repeat. Establish a routine and stick to it. Have daily crew briefings at the beginning and end of day, including weather reports and safety talks. Make sure everyone has all the information they need, even if you have to say things multiple times. Make sure everyone knows the plan.

4. Accept community/volunteer/crew goodwill and help, but be prepared with a backup plan(s) if help falls through (including the backup plan involving you having to do things yourself). Accept and encourage crew and community involvement, but be prepared to not rely on it. Your coworkers (and you) are human, and thus you have to be prepared for how you are going to get the project done if a crew member (or you) gets sick, has an emergency or other needs, or if community resources fall through. Also be prepared to go “old school.” On our project, we had high-tech mapping software, GPS units, offline cell apps, etc., and there were still times we had to rely on our radios and orienteering abilities.

5. The public/community is an asset. You are a guest of the local community and your project will be so much richer if you include local knowledge and insights and take local advice seriously.

Recommendations for Safety Education and Training for Graduate Students Directing Field Projects byKaitlyn E. Davis, Pascale Meehan, Carla Klehm, Sarah Kurnick and Catherine Cameron is out now in the latest issue of Advances in Archaeological Practice. The article is free to read until the end of May 2021.

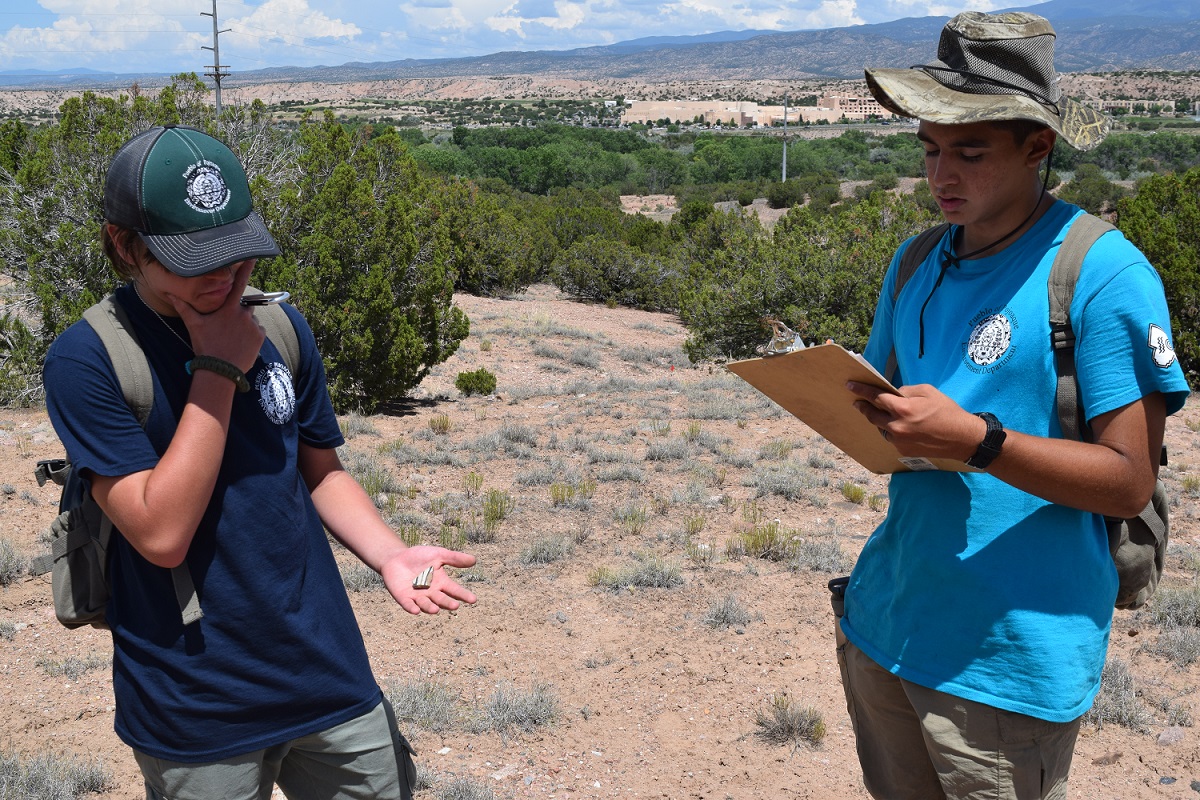

Image Caption and Credit: San Marcos area landowners helping identify locations for soil sampling as part of the Ancestral Pueblo Agricultural Landscapes (APAL) Project. Credit: Kaitlyn Davis.