“I think my enemy”: Carl Schmitt, sick of reading Arendt

Carl Schmitt, “the famous professor of constitutional and international law who later became a Nazi” (as Hannah Arendt once put it), continues to shock and intrigue, to convince and exasperate. Yet beyond wholesale rejection or uncritical devotion, a recent “historical turn” in Schmitt studies has made ample use of archival material to paint a more complex picture. This historicizing move has often shed new light on the interventionist, decisively political character of Schmitt’s writings over seven decades. Far from an abstract legal philosophy, Schmitt imagined himself as “the last knowing representative of ius publicum Europaeum,” resisting the onslaught of enemies with the force of his pen.

My recent article, Eichmann in Plettenberg: Carl Schmitt reads Hannah Arendt, joins this wave of historically grounded re-readings. On the basis of extensive marginalia from his personal Arendt collection, which contains four books as well as notes on Arendt’s 1968 essay on Walter Benjamin (published below for the first time), I trace the contours of Schmitt’s largely self-serving engagement with Arendt. There are surprising echoes between their political theories: from a critique of bureaucratic rule and an interest in the theological entanglements of political founding to a revaluation of public affairs after a modern collapse of inherited concepts. Yet what primarily drove Schmitt’s engagement with Arendt was not a search for understanding. He read Arendt through the lens of antisemitic hatred and instrumentally, in search of arguments for a potential criminal defense for himself. As I suggest on the basis of archival evidence, Schmitt was living in fear of his own prosecution and pictured himself in the shoes of Adolf Eichmann, sentenced to death in Jerusalem in 1961.

In a 1963 letter to Ernst Forsthoff, Schmitt called Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem “so exciting that I got sick from it for a couple of weeks.” He then linked this sickening effect to the memory of his 1945 legal brief on behalf of the steel tycoon Friedrich Flick, who had been convicted as a war criminal at Nuremberg. What was it about Arendt’s work that had such a sickening effect on Schmitt? In fact, there is a remarkable proximity between her analysis of Eichmann and Schmitt’s defense writings from 1945-47. The latter not only contain the outlines of a critique of depoliticized law that in many ways echoes Arendt’s account of the “banality of evil.” But Schmitt’s agreement with Arendt went further. Most surprisingly, in his 1945 Gutachten, he agreed with Arendt on the exceptional character of the Holocaust – a crime that could not be grasped within existing legal categories, but which nevertheless obliged “mankind […] to pass a sentence upon Hitler’s and his accomplices’ ‘scelus infandum’ (unspeakable atrocity). This sentence must be solemn in its form and striking in its effect.”

Upon reading Eichmann in Jerusalem, I suggest, Schmitt was reminded that he himself had provided arguments for the criminal prosecution of Nazi perpetrators – arguments that could now backfire. “We will be hanged, the dead body will be burnt, the ashes will be thrown into the sea, as with Eichmann,” Schmitt noted as late as 1975 in his copy of Adorno’s book on Benjamin. It was the fear of prosecution, of suffering the fate of Eichmann – an “existential panic” fueled by persistent antisemitism – that made Schmitt sick from reading Arendt.

Schmitt’s Arendt-Benjamin notes (1969/1970)

Max Planck Society Archives Berlin, Va/013 Va. Abt., Rep. 13 Sammlung Carl Schmitt, No. 7.

Reproduced here with the friendly permission of the Schmitt estate rights manager Florian Meinel. Sincere thanks to Matthew Landauer for his help in deciphering the Greek.

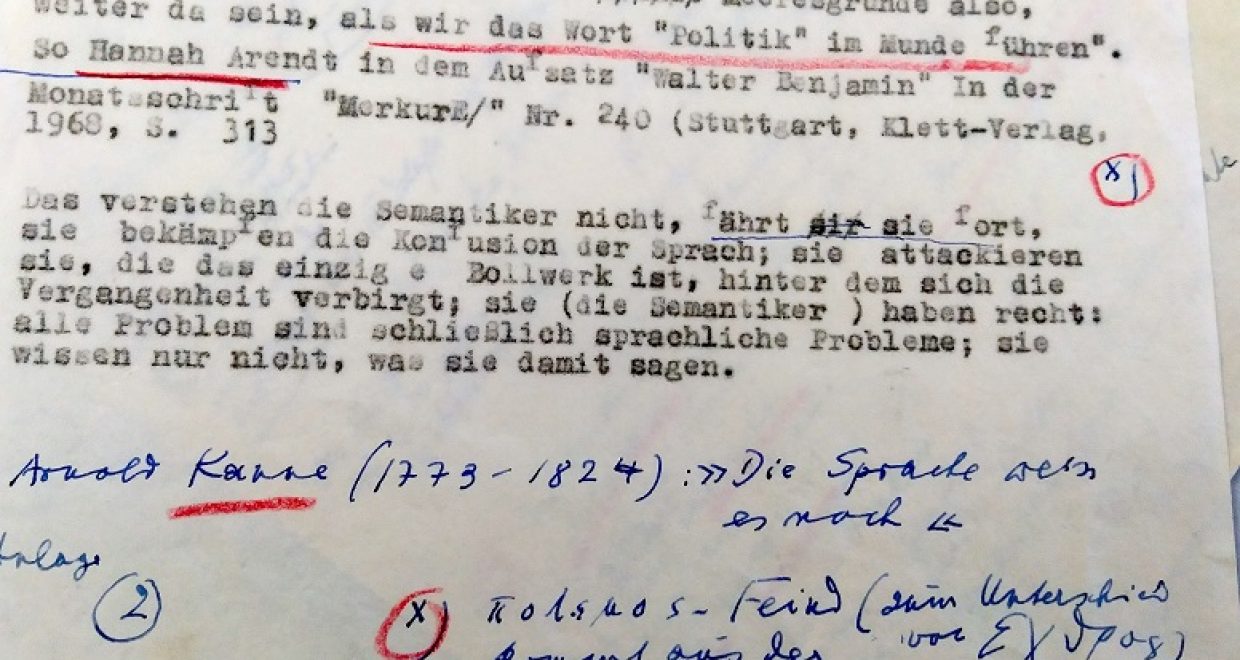

Note 1:

German original: “Die griechische Polis wird solange am Grunde unserer politischen Existenz, auf dem Meeresgrunde also, weiter da sein, als wir das Wort ‘Politik’ im Munde führen’. So Hannah Arendt in dem Aufsatz ‘Walter Benjamin’ in der Monatsschrift ‘Merkur’ No. 240 (Stuttgart, Klett Verlag, 1968, S. 313). X1 Das verstehen die Semantiker nicht, fährt sie fort, sie bekämpfen die Konfusion der Sprache; sie attackieren sie, die das einzige Bollwerk ist, hinter dem sich die Vergangenheit verbirgt; sie (die Semantiker) haben recht; alle Probleme sind schließlich sprachliche Probleme; sie wissen nur nicht, was sie damit sagen.—Arnold Kanne (1773–1824): ‘Die Sprache weiss es noch.’ Anlage: 2. X1: Πόλɛμος = Feind kommt aus der Wurzel Πόλ–ις (der Gegner im Bürgerkrieg, Πασις) (zum Unterschied von ɛχθρός [echthrós]).”

English translation: “The Greek polis will continue to exist at the bottom of our political existence—that is, at the bottom of the sea—for as long as we use the word ‘politics.’ Says Hannah Arendt in her essay ‘Walter Benjamin’ in the monthly review ‘Merkur’ No. 240 (Stuttgart, Klett 1968, p. 313). X1 This is what the semanticists do not understand, she continues, they fight the confusion of language; they attack it, the only bulwark behind which the past hides; they (the semanticists) are right; all problems are in the final analysis linguistic problems; they simply do not know the implications of what they are saying.—Arnold Kanne (1773–1824): ‘Language still knows it.’ Attachments: 2. X1: Πόλɛμος [pólemos] = Enemy comes from the root Πόλ–ις [pól-is] (the adversary in a civil war, στάσις [stasis]) (in distinction to ɛχθρός [echthrós]).”

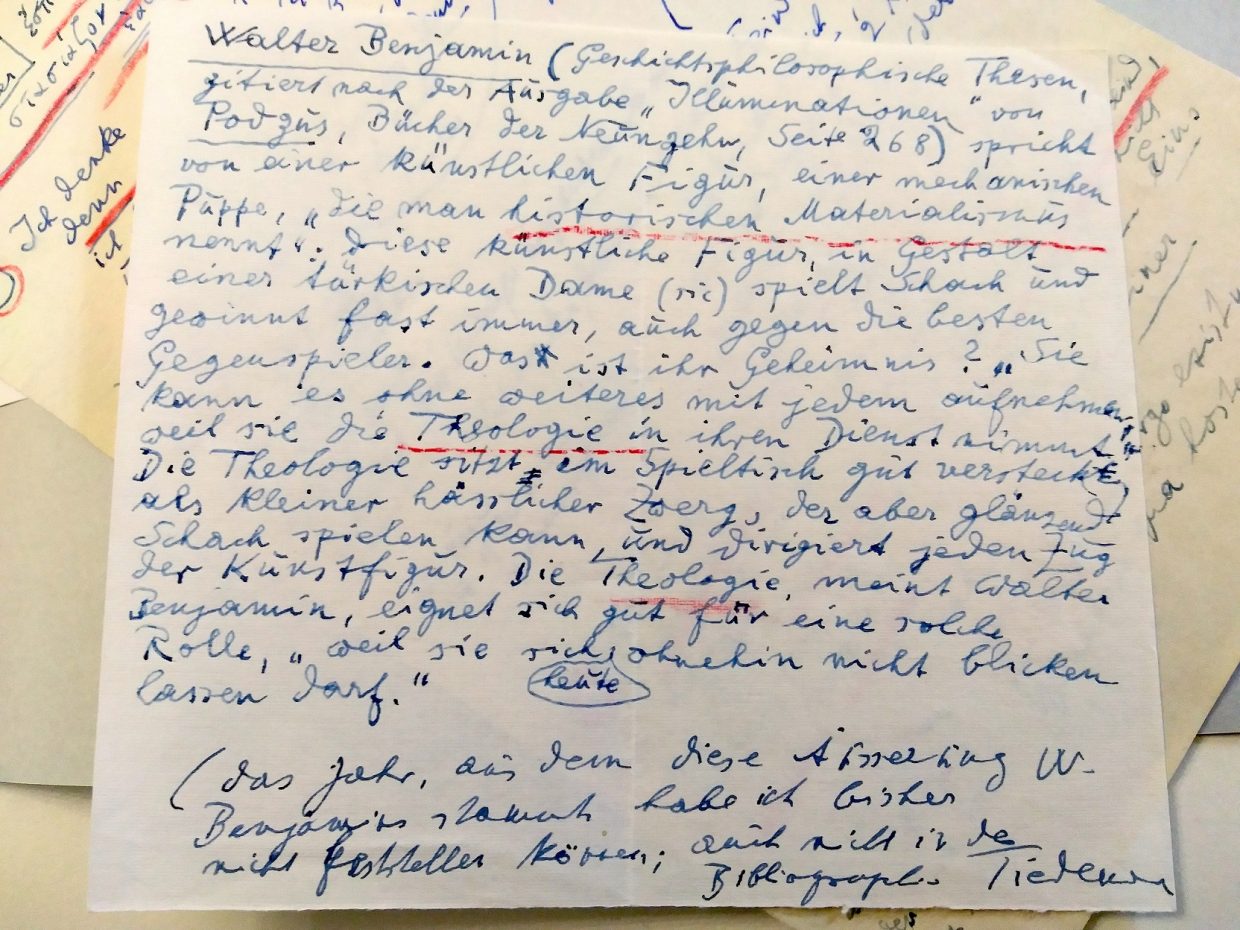

Note 2:

German original: “Walter Benjamin (Geschichtsphilosophische Thesen, zitiert nach der Ausgabe “Illuminationen” von [Friedrich] Podzus, Bücher der Neunzehn, Seite 268) spricht von einer künstlichen Figur, einer mechanischen Puppe, ‘die man historischen Materialismus nennt’: Diese künstliche Figur in Gestalt einer türkischen Dame (sic) spielt Schach und gewinnt fast immer, auch gegen die besten Gegenspieler. Was ist ihr Geheimnis? ‘Sie kann es ohne weiteres mit jedem aufnehmen, weil sie die Theologie in ihren Dienst nimmt.’ Die Theologie sitzt im Spieltisch gut versteckt, als kleiner hässlicher Zwerg, der aber glänzend Schach spielen kann und dirigiert jeden Zug der Kunstfigur. Die Theologie, meint Walter Benjamin, eignet sich gut für eine solche Rolle, ‘weil sie sich (heute) ohnehin nicht blicken lassen darf.’ (Das Jahr, aus dem diese Äußerung W. Benjamins stammt habe ich bisher nicht feststellen können; auch nicht in der Bibliographie [von Rolf] Tiedemann)

English translation:

“Walter Benjamin (Theses on the Philosophy of History, cited according to the edition “Illuminationen” by [Friedrich] Podzus, Bücher der Neunzehn, page 268) speaks of an artificial figure, a mechanical puppet, ‘which one calls historical materialism’: This artificial figure in the shape of a Turkish lady (sic) plays chess and wins almost always, even against the best opposing players. What is its secret? ‘She can easily face off anybody because she puts theology into her service.’ Theology is sitting well hidden inside the chess table, as a little ugly dwarf, but one which plays chess brilliantly and which directs every move of the artificial figure. Theology, Walter Benjamin believes, is well placed for this role, ‘because she is (today) not allowed to show up anyway.’ (I have until now been unable to determine the year from when this statement by W. Benjamin originates; not even in the bibliography [by Rolf] Tiedemann)

Note 3:

German original:

To en – das Eine; die Einheit; Eins

Für J. Schickel

5/8/60

[illegible] 31/5/70 C.S.

Hic Denker, nicht Dichter

Esti gar kai

to hen stasiazon pros

heauto

(1) Ich denke, denn ich habe Feinde

Ich denke denn ich habe Feinde [written in Greek alphabet]

Ich denke, denn ich habe Feinde

Ich denke, also bin ich nicht (sicher), denn ich bin gefährdet durch meinesgleichen.

Der Feind ist mit meiner/der Situation gegeben;

Daraus, dass ich mir meiner gefährdeten Situation bewusst werde, entsteht die Feindschaft auf beiden Seiten (C. S. ich habe die Feindschaft nicht erfunden!)

Ich denke, denn ich habe Feinde

Der Feind ist 1) der Andere 2) meinesgleichen

Ich denke mich, also bin ich doppelt, 2x, geteilt, ich bin das (der) Gedanke

(2) Ich denke, infolgedessen (also) habe ich Feinde

Der Feind / Andere entsteht daraus, dass ich mir seiner bewusst werde.

Denke den Feind

Denke Feinde [in Greek alphabet]

Ich denke meinen Feind, also sind wir nicht zwei, sondern Eins oder Einer.

Andere

Ich Ezeuge ihn

Wie Gott Vater

Den Gott Sohn

Den Logos

Denken feindet

Feinde denken, ergo existente qualitate qua hostes

English translation:

To en – the One; the Unity; One

For J. Schickel

5/8/60

[illegible] 31/5/70 C.S.

Hic Thinker, not Poet

Esti gar kai [for it is also]

to hen stasiazon pros [the one fighting against/disagreeing with]

Heauto [itself]

(1) I think, because I have enemies.

I think, because I have enemies

I think, because I have enemies

I think, therefore I am not (safe) because I am put in danger by my equal

The enemy is given with my/the situation

Out of my becoming aware of my endangered situation, enmity emerges on both sides (C. S. I did not invent enmity!)

I think, because I have enemies

The enemy is 1) the Other 2) my equal

I think myself, therefore I am doubled, 2x, divided. I am the thought (the one who is thought).

(2) I think, therefore I (also) have enemies.

The enemy/the Other emerges from my becoming aware of him.

Think the enemy

Think enemy

I think my enemy therefore we are not two but one

Other

I create him

Like God Father

Creates God Son

Creates Logos

Thinking creates enemies

Thinking enemies, ergo existente qualitate qua hostes