Their Wins Are Their Own, Not Ours

In July of 2021, Zalia Avant-garde, an eighth grader from Harvey, Louisiana, became the first Black student to win the Scripps National Spelling Bee in the organization’s ninety-six-year history.[1] Almost a year later, Haley Taylor Schlitz, who graduated from high school at thirteen and earned her undergraduate degree at sixteen, is making headlines as the youngest Black law school graduate in the United States.[2] The extraordinary achievements of these gifted young women highlight their exceptional abilities, while also revealing the slow progress surrounding the Black educational experience in America.

The remarkable accomplishments of these two young women implore both applause and inquisition. Why has it taken ninety-six years for a Black student to win the title? What does the thirty-five-year gap between the achievements of Haley Taylor Schlitz and Stephen Baccus say about the educational debt here in America? [3]. How do these narratives fuel conversations about supporting and uplifting gifted Black students? As historians, educators, and others examine the experience of Black youth in the USA today, these examples call for both celebration and continued investigation of our education system, in the past as well as in the present.[4]

Sevan Terzian’s analysis of Lillian Steele Proctor’s “A Case Study of Thirty Superior Colored Children in Washington, D.C.” provides a thorough critique of Proctor’s research, unpacks the experiences of gifted African American students in the United States, and sets the foundation for these questions. Looking to expound on the narratives surrounding the gifted Black child, both the original Master’s thesis by Proctor in the 1930s, and Terzian’s more recent analysis in HEQ, help us to understand how and why Zalia and Haley’s titles are well-deserved but problematic.[5]

According to Terzian, one of the major contributions of Proctor’s work to the field was her emphasis on the relationship between environment and student achievement. Prior to Proctor’s work, studies of African American student performance failed to recognize the potential impact of home life, teacher support, parental roles, sociopolitical upheaval, and poverty on Black student achievement.[6]

Today, there is a growing amount of research that marries these issues to academic achievement; however, in real time, research infrequently makes it into the classroom, and students that are simply coping with life’s hardships are labeled as oppositional, unmotivated, and unwilling to learn.[7] This lack of research-based intervention in the classroom could be due, in part, to two main factors: (a) systems and educators have only recently began to solve educational inequities with data-based decision making, and (b) teachers often lack the training and orientation needed to translate research into practice.[8] The outcome: a pattern of students, often Black and Brown, that are unfairly tracked, mislabeled, and overlooked. Students who could go on to be the next Zalia or Haley are never given the opportunity to do so.

A second pivotal point of Terzian’s analysis and Proctor’s work looks at the prevalence of deficit thinking and the longstanding implications of racist doctrines such as the eugenics movement.[9] For years, researchers were adamant that Black students were “inherently inferior in intellect.”[10] Recent research points to the vestiges of these beliefs in the thoughts and actions of contemporary teachers.[11] According to Terzian, this ideology seeped into classrooms and dictated the efforts of teachers and their perception of student abilities.[12] Because of research from scholars such as Claude Steele, we know this to lead to the development of stereotype threat amongst students whereby students’ perceptions of teachers’ beliefs hinder their self-efficacy.[13] This, in turn, leads to poor performance from those targeted students. While some students can overcome the vicious effects of these ideologies, others succumb to it. Black students that would otherwise be identified as gifted are overlooked and therefore lost in the undertow of an already inequitable educational experience.

A final point that emerges from this piece is the idea of social closure. According to Proctor’s work, African Americans appeared to be closed off from the resources needed to nurture the gifted child. There were few community programs available and resources at schools were scarce—with the result that even if parents wanted to support the budding creativity and intellectualism of their child (and most did), there were virtually no means to do so. This is an important variable even in the contemporary context as we hear narratives falsely asserting that Black parents do not value education. Haley’s story is a perfect example of this. Not only did her parents value her education, but in the face of social closure and limited access to quality education options, they created their own opportunities for their daughter through homeschooling.[14]

Proctor’s seminal work and Terzian’s hard-hitting analysis forces us as policy makers, practitioners, and researchers to be slow to base conclusions about the American education system’s efficacy in serving marginalized populations on a few anomalies and success stories. It challenges our celebration of “excellence in spite of” and looks to examine the arduous educational experiences of African American students in general and the gifted Black child experience in particular. Are Haley and Zalia’s stories inspiring? Absolutely! Does that mean that we should rest our research and policy laurels on their achievements? Absolutely not!

[1] Dana Farrington and Emma Bowman, “1st African American to Win the Spelling Bee Also Holds 3 Basketball World Records,” NPR, July 9, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/07/08/1014312875/scripps-spelling-bee-winner.

[2] Chinekwu Osakwe, “Texas Teen Who Got Diploma at 19 Says She’s Youngest Black Law School Grad,” Reuters, May 17, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/legal/legalindustry/youngest-black-law-school-graduate-us-gets-her-diploma-19-2022-05-13/.

[3] A Jewish student from New York, Stephen Baccus was sworn in as the nation’s youngest attorney at the age of 17 in 1986. Gloria Ladson-Billings, “From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools,” Educational Researcher 35, no. 7 (Oct. 2006), 3–12, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X035007003.

[4] Paula Span, “Trials of the Teen-Aged Lawyer,” Washington Post, February 25, 1987, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1987/02/25/trials-of-the-teen-aged-lawyer/812de938-c8f2-4289-9884-469e717d88ad/.

[5]Lillian Proctor Steele, “A Case Study of Thirty Superior Colored Children in Washington, D.C.” PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1929.; Sevan G. Terzian, “‘Subtle, Vicious Effects’: Lillian Steele Proctor’s Pioneering Investigation of Gifted African American Children in Washington, DC.” History of Education Quarterly 61, no. 3 (Aug. 2021), 351–71, https://doi.org/10.1017/heq.2021.22.

[6] It should be noted that these issues are a natural byproduct of the inequitable systems and policies that created them.

[7] Angel L. Harris, Kids Don’t Want to Fail: Oppositional Culture and Black Students Academic Achievement (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 3. For sources of stress for teens, see American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, “Stress Management and Teens,” Jan. 2019, https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Helping-Teenagers-With-Stress-066.aspx.

[8] Paula J. Stanovich and Keith E. Stanovich, “Using Research and Reason in Education: How Teachers Can Use Scientifically Based Research to Make Curricular & Instructional Decisions,” National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, https://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/using_research_stanovich.

[9] According to Davis and Museus (2019), deficit thinking holds students from historically oppressed populations responsible for the challenges and they face. See Lori Patton Davis and Samuel D. Museus, “What Is Deficit Thinking? An Analysis of Conceptualizations of Deficit Thinking and Implications for Scholarly Research.” NCID Currents 1, no. 1 (2019), http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/currents.17387731.0001.110.

[10] Sevan G. Terzian, “‘Subtle, Vicious Effects’: Lillian Steele Proctor’s Pioneering Investigation of Gifted African American Children in Washington, DC.” History of Education Quarterly 61, no. 3 (Aug. 2021), 351–71, https://doi.org/10.1017/heq.2021.22.

[11] Bruce Douglas et al., “The Impact of White Teachers on the Academic Achievement of Black Students: An Exploratory Qualitative Analysis,” Educational Foundations 22, no. 1-2 (Win.-Spr. 2008), 47-62; Mary E. Contreras, “The Effects of Teacher Perceptions and Expectations on Student Achievement,” EdD diss., UC San Diego, 2011, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b84k07z.

[12] Terzian, “Subtle, Vicious Effects,” 353.

[13] Claude M. Steele, Whistling Vivaldi: And Other Clues to How Stereotypes Affect Us (New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 2010).

[14] Osakwe. “Texas Teen Who Got Diploma at 19 Says She’s Youngest Black Law School Grad.”

“Subtle, vicious effects”: Lillian Steele Proctor’s Pioneering Investigation of Gifted African American Children in Washington, DC by Sevan G. Terzian

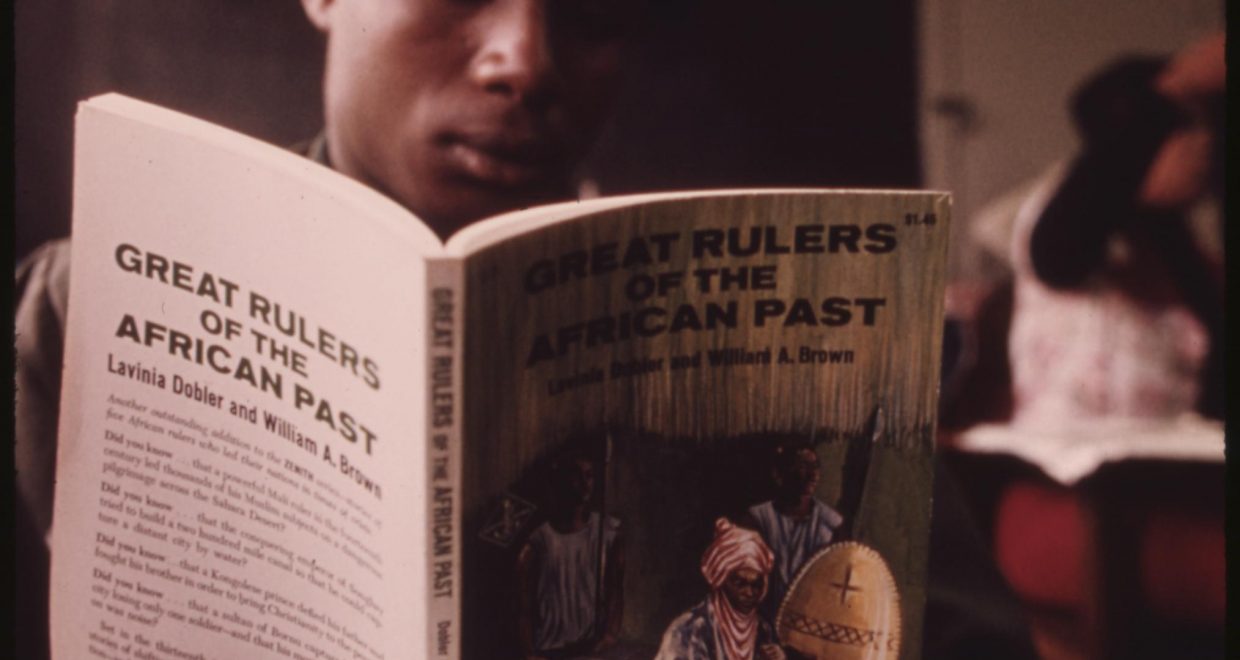

Image credits: Photograph by John H. White, Black Student in a Black Studies Class in a West Side Chicago Classroom Reading a Book About Great Rulers in Africa’s Past, 10/1973, The U.S. National Archives, 412-DA-13811.