Forest birds and plantations

Since the publication of Silent Spring in 1962, debates around the sustainability of food production have centred largely on the environmental impacts of arable crops and meat production. More recently, however, attention has shifted increasingly to commodities produced from trees grown in plantations – particularly in the tropics, where they often replace natural forest. Commodities such as palm oil, cocoa and coffee can have serious impacts on biodiversity, as the wildlife they support tends to be very much poorer than that found in natural habitats.

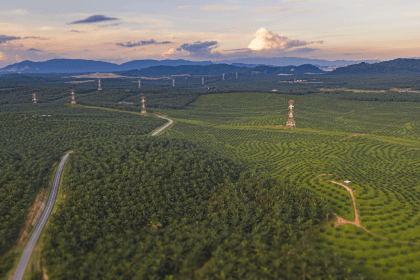

Tropical forests harbour a very high proportion of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity, supporting wildlife communities that are more diverse and more species-rich than any other habitat. The rich plant communities they support include a handful of species that produce commodities that now have a high global value; these include oil palm (a species native to west and southwest Africa), coffee (a native of the highland forests of Ethiopia), cocoa and rubber (both of which occur naturally in Amazonia). Rising demand for these products, which were originally harvested from trees growing wild in the forest, has driven the expansion of single-species plantations, usually planted in areas formerly occupied by natural forests, and the spread of commodity production to parts of the world outside the crop species’ natural ranges. Most of the world’s oil palm, for example, is grown in monocultures in Indonesia and Malaysia, far outside its native range. Production is often intensive, using chemical sprays and removing any competing plants.

The impacts on biodiversity can be severe. Numerous studies have shown that the rich, complex communities of wildlife present in native forests are largely lost when they are replaced by monocultures of crop trees. The general pattern, recorded in many different parts of the world, is that most forest specialist species simply disappear, to be replaced by a very small number of adaptable and widespread generalists. Many iconic species, such as the dazzling but Critically Endangered Gurney’s Pitta, face global extinction through the spread of plantations into their remaining native forests.

However, the loss of biodiversity can be reduced. Many crops can be grown under the shade of native trees, which retain a proportion (though generally not all) of their indigenous wild species. Furthermore, the quality of crops such as coffee and cocoa, some of which are grown under natural shade, tends to be higher than that of the same crops grown in monocultures. They can therefore attract higher prices, more than compensating growers for the lower yields.

Many conservation organisations work with growers producing more sustainable products to help promote their products; it is now possible to buy bird-friendly coffee and chocolate. Furthermore, researchers have shown that there is more than enough already-degraded land to meet future production estimates without felling new areas of forest. The challenge is now to work with growers to reduce the environmental footprint of their current and future operations.

These topics are covered in greater depth in this month’s tenth and final centenary collection of BCI papers, made freely available by Cambridge University Press for a limited period to mark the 100th anniversary of BirdLife International. The release of this collection coincides with the UN Biodiversity Conference (CBD COP15) in Montreal, from 7 to 19 December 2022, where the world’s governments will negotiate and adopt a ‘post-2020 global biodiversity framework’ – a roadmap for the conservation, protection, restoration and sustainable management of biodiversity and ecosystems for the next decade.

Paul Donald, Senior Scientist, BirdLife International