On the puzzling geography of blowguns

You may be familiar with the blowgun, which appears as a five-minute DIY, life-saving weapon in some popular movies and series (e.g., Apocalypto, McGyver, Love and Bullets). In real life it takes much longer to make such an artifact, nowadays it is also a sport and can be used for remote drug delivery for animals at zoos. The blowgun, a tube from which a projectile (usually a dart or a clay pellet) is propelled by the force of the human breath, has been constructed and used by humans for more than a millennium. Some early examples on the use of blowguns are depicted in archaeological artifacts such as in Moche and Maya vases (example below) and reliefs in the 9th-century Buddhist temple of Borobudur (Indonesia).

Ethnologists and explorers have documented the traditions of this weapon in many societies worldwide; from this we know that the main two functions have been hunting and warfare. It was discovered that a substance now widely known as curare was (and still is) used by many Central and South American societies to poison their darts and paralyse tree-dwelling prey such as monkeys and birds. Blowguns in combination with curare are extremely successful in dense forests because social animals do not even realize that a member of the group has been shot with this silent weapon, therefore increasing the chance killing more than one animal of a group. Geographically, the traditional use of blowguns has a wide, but discontinuous distribution in tropical areas across the Pacific. South America and Southeast Asia are the hotspots (see map below) when it comes to traditional use. Similarities in use and construction have prompted debates on whether the weapon was separately invented on both sides of the Pacific, or this reflects diffusion across a vast ocean. The paper “A global database on blowguns with links to geography and language” addresses these questions. The team behind this study includes a molecular anthropologist that works on genetic and linguistic diversity in human populations, an ethnobotanist working on conservation of biological and cultural heritage and cultural evolution workers from Zurich. We were lucky to be joined by Prof. Emeritus Stephen C. Jett from USA, who devoted a good part of his academic life to understanding blowguns, their geographic patterns and the potential explanations to those patterns. His paper called “The development and distribution of the blowgun” is a standard reference on the topic.

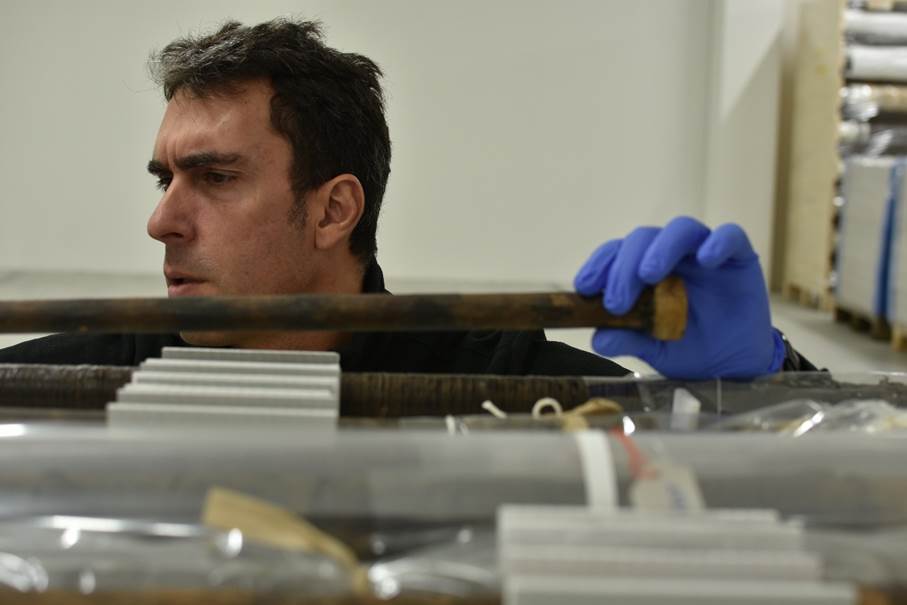

Here, we used a classification system proposed for South American blowguns and extended it for use in a world sample that was gathered from literature searches (including those in the eHRAF World Cultures database) and own collection-based work (as shown below). We mostly obtained data on which societies (ethnologically speaking) use blowguns, which types of blowguns and projectiles they use and to increase interoperability with other databases out there, we linked our ethnological information to language units (‘languoids’) available in the Glottolog database. Our results indicate that the geographic distribution of blowguns cannot be explained by a single factor, all types of blowguns are seen in distant parts of the world, and geographic closeness and cultural connections certainly play a role. A case-study on the use of blowguns in groups of Austronesian language speakers shows clade-specific preferences across the tree. In terms of projectile use, the darts are by far more frequent and only exclusively used in the ‘double-whole’ type of blowguns; pellets are more likely to be used in ‘single’ type blowguns than all the other types.

For more on this topic, read the full article, A global database on blowguns with links to geography and language, in Evolutionary Human Sciences.

Gabriel Aguirre-Fernández is a palaeontologist at the University of Zurich with interests on cultural evolution. His paper “Panpipes as units of cultural analysis and dispersal” was also published in the Evolutionary Human Sciences Journal. This work is part of our ongoing efforts to contribute to our understanding of cultural macroevolution in South America (https://www.msanchezlab.net/)