The “Dreamers” Are Just As Politically Active as Native-Born Population

Are immigrants in the U.S. politically active? Do they vote, engage in political campaigns, and participate in protests as frequently as the native-born population? The answer is not obvious as evidence points to contrary conclusions. On the one hand, aggregate data such as this U.S. Census Report shows that immigrants (those who were born outside the U.S.) were less likely to register and vote compared to the native-born population. On the other hand, young immigrants appeared to be highly active when it comes to issues concerning immigrants like themselves, such as demonstrating support for the DREAM Act.

From a political science perspective, the question about immigrants’ political participation is indeed puzzling: why do immigrants still participate less in politics, when many have achieved comparable and sometimes even higher levels of socioeconomic status (SES) relative to the native-born citizens? Why was it the case that SES could account for the lower levels of political participation of some groups, for example, African Americans before the 2000s, but it could not account for the lower levels of participation of immigrants? In our article, Why Do Immigrants Participate in Politics Less Than Native-Born Citizens? published in the January 2020 issue Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics, we answered this question using the formative years theory situated in the political socialization literature.

We argued that one’s immigrant status, per se, is NOT a contributing factor to lower levels of political participation.

Immigrants who moved to the U.S. at a young age, we theorized, are likely to participate in politics at a rate comparable to the native-born population because these immigrants spent their formative years in the U.S. and therefore was socialized in the U.S.’s political environment. For these immigrants, their immigrant status should bear no effect on their political participation. Immigrants who moved to the U.S. at an older age are likely to participate in politics at a lower rate, because these immigrants spent their formative years in their countries of origin, in political environments that were often dissimilar to that of the United States’. For this latter immigrant group, their immigrant status, associated with their formative years’ experiences aboard, could possibly lower political participation.

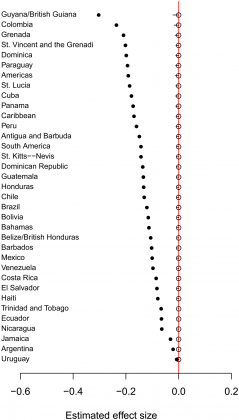

The analysis results fully support our theorization. Using the U.S. Census’ 1994–2016 Current Population Survey and their Voting and Civic Engagement Supplements as data sources, we employed a hierarchical model to simultaneously account for region-, country-, and individual-level factors. We found that immigrants who moved to the United States at a young age participate in politics at a rate that is indistinguishable from the native-born population, and those who migrated at an older age participate less. The fact that over 60% of the immigrant population moved to the United States as adults is a main factor that contributes to the political participation gap between immigrants and the native-born population. In the figure below that shows the simulated results, the solid dots represent Latin American immigrants who moved to the U.S. after 25, and the circles represent Latin American immigrants who moved to the U.S. before the age of 5, and the red line is adjusted at zero, representing the levels of political participation of the native-born population. While those migrated at an older age appeared to participate in politics less, those who migrated before the age of 5 is indistinguishable from the native-born population.

In the immigration debate in recent years, the young immigrants’ voice that we often heard is a reflection of the fact that these young people, many of whom “dreamers,” are just as politically active as the native-born citizens. Our analysis suggests that, despite their uncertain fate regarding path towards citizenship, many of these young immigrants managed to use resources available to them and actively participated in a democracy that is yet to fully embrace their presence.

Ruoxi Li, California State University San Marcos

This blog is based upon Li and Jones’ article in the latest issue of the Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics which you can read free of charge until the end of April 2020.