Glass encounters from Pompeii

Hilary Cool, Barbican Research Associates, reflects on how she tackled the topic of her forthcoming article in Papers of the British School at Rome which is due to be published later this year.

It is always unwise to agree to do something without thinking through the consequences. My involvement with the small finds and glass vessels from the excavation of Insula VI.1 in Pompeii came from a casual encounter with the excavation team in 1999. My husband and I were having a day out to the city as part of a holiday in Naples. I returned in 2001 to produce a short report on the glass that I had been shown, calculating that it would take me a fortnight. Fifteen years later, I am just completing the rather large book on the 5000 or so identifiable objects the excavations eventually produced.

This work has had to be fitted into such free time as my work within the commercial sector of British archaeology allows. In the day-job, the research I conduct is planned and justified meticulously in advance. It is the way you get the client to fund it! The same cannot be said for my Pompeii work which, in the absence of any funding body, is free to wander into all sorts of areas. One of these is the question of what the 500 or more glass counters found were used for, and this is the subject of my forthcoming article in the Papers of the British School in Rome.

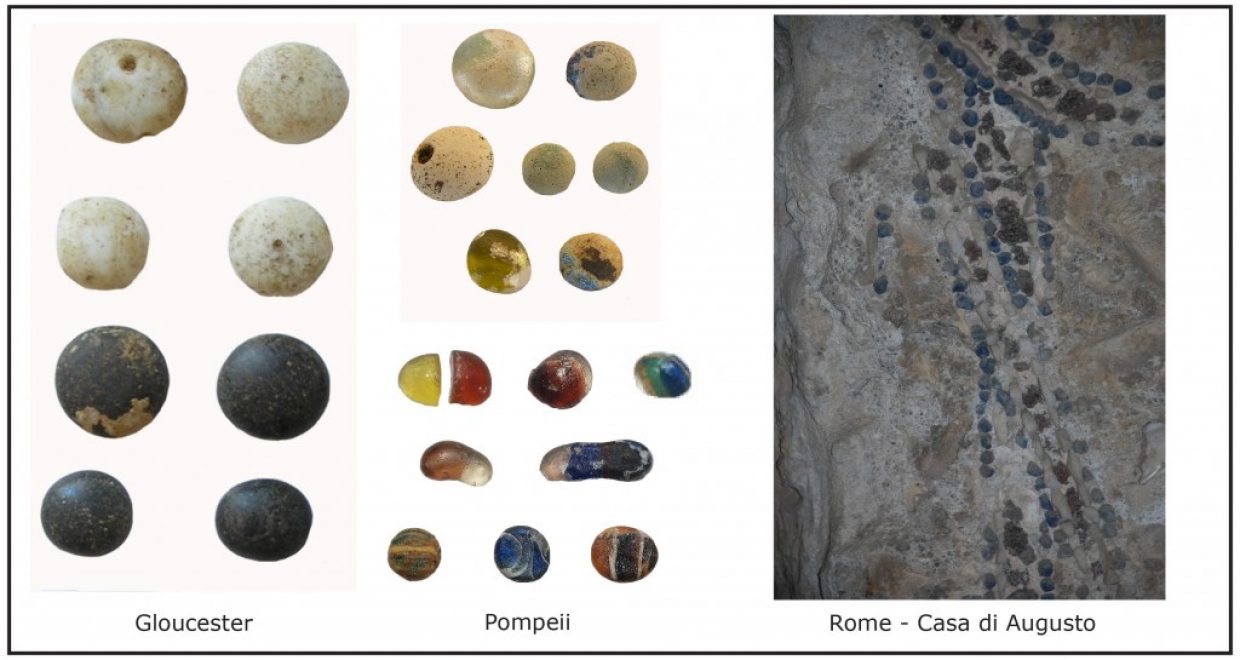

The Romans did have board games which used counters. One – ludus latrunculorum – was a game akin to chess or draughts where the aim was to win pieces from your opponent. The other game – ludus xii scripta – was played with dice and was akin to backgammon, where you aimed to play your counters off the board before your opponent did. In my home environment of Roman-Britain, most plano-convex discs of glass can be casually assigned to the recreation category. Counters like this, made of black and white glass, are a regular feature of first to second century AD assemblages and, from time to time, conveniently appear in graves with dice. They even, in one very rare occurrence, are laid out on a board ready for play.

So, when I started to encounter glass counters at Pompeii, I thought I had evidence of the sort of games that can be seen depicted in the paintings on the walls of bars in the city. In one there is an enchanting sequence where the evening of a pair of drinkers can be seen. They argue over many things, including who has won a game of xii scripta, before being banned by the barmaid for bad behaviour.

Increasingly though, the counters I was cataloguing at Pompeii didn’t seem to match what was appropriate for a gaming piece. You need to have easily differentiated sets for each player. This is what is seen in known sets from graves where normally there is a simple division between black and white counters such as ones from Gloucester which I illustrate above. The literary sources back this up. They too talk of black and white counters. My Pompeii counters, however, were all sorts of colours and different sizes. Some were a single colour, some combined different colours, and the range of shades encountered taxed even me, as a skilled glass specialist, to differentiate. These were not the sort of things that the drinkers in the bar pictures could have used with any ease, especially after several glasses of wine.

The paper describes how I disentangled which plano-convex glass discs were indeed used for gaming, and which must have been used for something else. What that something else might have been is intriguing. I suspect it is an aspect of interior decoration. There is some evidence of glass ‘counters’ in ceiling and wall decoration in Rome, but very possibly they could have decorated wooden furniture and fittings as well. Glass survives. Wood doesn’t.

The Pompeii work in its wider aspects has often challenged my preconceptions of what ‘Roman’ material culture actually is. Within Roman Britain we see a lot of changes in the mid first century AD after the conquest which we ascribe to ‘becoming Roman’. My contemporary patterns at Pompeii are different. Acquiring a working knowledge of how those Pompeian patterns relate to the rest of contemporary Italy has been an interesting challenge. My sort of work requires a considerable amount of interrogation of published sources which are frequently obscure. The discovery of the British School at Rome Library has been a godsend, and since 2012 I have been steadily mining it when I can find time to visit. I’m still not sure if I now know what ‘Roman’ material culture is, but exploring that further is another project.

Hilary Cool’s full article will be published in volume 84 of Papers of the British School at Rome in October 2016.

Sign up for content alerts or follow us on Facebook and Twitter to be the first to know when the article is published.

Image: Counters form Gloucester, Pompeii and set into the wall of the Nymphaeum in the Casa di Augusto, Rome (Source: Author and Mike Baxter).

Explore more of Hilary Cool’s research with a free excerpt of her book Eating and Drinking in Roman Britain, which is available to buy in hardback and paperback.