The ‘Roman’ Modernism of Innocenzo Sabbatini’s Public Housing

Aristotle Kallis, Professor of Modern History at Keele University and one of the editors of PBSR, discusses his forthcoming article, ‘Rome’s singular path to modernism: Innocenzo Sabbatini and the “rooted” architecture of the Istituto Case Popolari (ICP), 1925-1930’, in Papers of the British School at Rome (2017), which will shortly be published via FirstView on the journal’s Cambridge Core web-page.

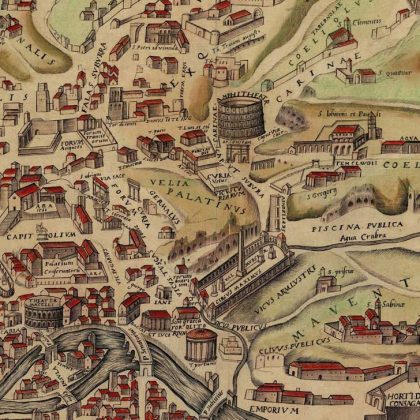

Rome, the ‘city of visible history’ as George Eliot described it, a place with such an outrageous concentration of world-heritage-status monuments, ruins, and museums, has been largely shaded out of the picture of Italian architectural modernism. The standard story goes as follows: modernism, as an avant-garde movement predicated on a rupture with the past, grew in the north Italy during the 1920s, vied for influence over the Fascist regime in the early 1930s but eventually lost to the more syncretic and monumental official style of the regime (the stile littorio). This story is one filled with radical ideas, extraordinary plans for buildings and towns that were largely never executed, flamboyant characters but also tragic personal stories (Gian Luigi Banfi of the famous BBPR group and the editor of the architectural journal Casabella Giuseppe Pagano perished in the Mauthausen camp system, only weeks before the end of the war; Giuseppe Terragni returned from the front broken and finally died in 1943 at the age of 39). In this story, Rome features as a predominantly hostile space and cultural context, where modernists fought their most significant symbolic battles but – with very few exceptions in the early 1930s – were crushed.

During the time I spent as fellow at the British School at Rome, taking advantage of that immense privilege of living in the city that I was researching, I stumbled upon the elegant, low-key layers of a Rome that I had never sought or appreciated before. This was neither the Rome of official architecture that I had focused on in my previous projects nor the phantom Rome of (largely unrealised) streamlined modernist designs and urban interventions in the historic core of the city. It was instead the Rome of the unsung 1920s – the Rome of housing, of new vernacular styles, of humble yet thoughtfully designed new neighbourhoods appended to the metropolitan core. The historic centre of Rome may indeed be hard to describe as fecund and hospitable ground for avant-garde modernism and particularly its polemical Italian branch of razionalismo; but just a short distance away from the main tourist areas lies a diverse and fascinating register of experimentation with a brand of unmistakably Roman modernism – a modernism that, while internationally-minded, remained rooted in, and in dialogue with, the rich cultural and ambiental context of the city.

This register holds many surprises. Its most fruitful phase coincides with the 1920s – usually seen as a somewhat ‘lost’ decade when compared to the explosion of modernist energies, in Rome and elsewhere in Italy, during the first half of the 1930s. It is also a register of built architecture as opposed to the bulk of the designs of interwar Italian rationalists that remained on paper. Finally, much of this register is associated with one rather unlikely agent – the Institute of Public Housing of Rome (Istituto Case Popolari, ICP); in other words, a public body with very modest financial resources, tasked to build affordable houses for those who had lost their abode (because of the Fascist regime’s vast demolition projects) or could no longer afford accommodation in the city (due to rapidly rising rental prices).

In my article I trace the extraordinary – in scale, quality, and design – architectural production of the Roman branch of the ICP during the period between 1925 and 1930. This period was the most prolific and creative in the history of the Institute. It also, inevitably, throws into relief the role of a single figure – the architect Innocenzo Sabbatini. Born in Osimo, near Ancona, in 1891, Sabbatini came to Rome to work for the ICP and rose rapidly to become head of the Institute’s Projects Team. Initially influenced by the regional style of barocchetto (a reworking of the city’s baroque vernacular traditions), he embarked on a singular journey of experimentation with new forms of public housing and with a visual language that was both modern and unmistakeable ‘situated’ in the traditions and the ambience of Rome.

Sabbatini’s architectural legacy for the ICP is extensive and supremely important for the history of modernism in Rome. Nevertheless, it is concentrated in time (1923 to 1930) and clustered around a relatively small number of neighbourhoods – Tiburtino, Appio, Testaccio, Trionfale, and the suburb of Garbatella. In the article, I examine the three arguably most innovative ICP projects of this period bearing Sabbatini’s signature. The first two were constructed: the Albergo Rosso (the most distinguished member of a group of four innovative ‘hostels’ originally constructed to provide temporary, good-quality accommodation for homeless people) on the edge of Garbatella; and the so-called Casa del Sole on Via Sant’Ippolito in Tiburtino. The third project – a gargantuan housing complex, structured as a Roman variation on the type of unité d’habitation – on the tip of the Trionfale district – remained on paper. Through these three projects, I seek to trace a singular Roman road to architectural modernism that predated the ‘heroic’ phase of razionalismo during the early 1930s – a kind of regional architectural ‘fourth way’ between baroque historicism, international-style modernism, and Piacentinian stripped-down classicism.

Sabbatini’s Albergo Rosso was included in the first exhibition of rationalist architecture that took place in Rome in 1928. Even if it was by a wide margin the most traditionally-inspired design shown at the exhibition, it was recognised as modern in terms of its programmatic sensibility, design experimentation, and construction methods. By the early 1930s, when the second exhibition of rationalist architecture was held in Rome, there was far less space for this kind of mediation of situated modernism that Sabbatini and his ICP team were so committed to. Overshadowed by far more colourful characters, flamboyant designs, and the rationalists’ aggressive rhetoric of a rupture with the past, this architectural production deserves to be reappraised and re-appreciated – not only as a regional ‘style’ but also as a fascinating alternative future of Italian modernism that never really was.

Sounds like an incredibly interesting article providing deeper insight on an aspect of Roman architecture that must have been largely forgotten in mainstream literature on the topic. The architecture of functionality seems to also hold a considerable Roman design history within it, which must make for a fascinating counterpoint with conventional functionality.