Author, Tim Longman, responds to Trump’s recent comments

Although President Donald Trump’s recent comments disparaging African countries have drawn international condemnation, many Americans unfortunately share his perception that Africa is a miserable place where no one would choose to live. As a professor of African politics, I find that many students bring to class similar negative conceptions of Africa, and fighting these prejudices is a major goal of my teaching and research.

To confront the notion that Africa is a backward and violent continent full of hopeless, helpless people requires both highlighting the positive stories that are generally neglected and providing greater context and understanding for the continent’s problems. For example, although the international press has generally failed to notice, Africa has experienced major democratic advances in the past several decades. Competitive elections are held regularly in many countries, and the peaceful democratic transfer of power has become the norm from Senegal to South Africa to Tanzania. Nearly every country now has vibrant human rights organizations, and advances in women’s rights and political representation have been impressive; women now make up over 30 percent of parliament in 14 countries, and Rwanda has the highest percentage of women parliamentarians in the world. Many of the world’s fastest growing economies are in Africa, and a construction boom is putting up office towers, shopping malls, and upscale residential neighborhoods in cities across the continent.

While highlighting Africa’s little known positive stories is important to confronting negative images of the continent, ignoring the major challenges faced by many African countries would be disingenuous. Poverty is in fact widespread, wars and social strife are too common, and dictators are numerous. Yet understanding the sources of Africa’s ills can go a long way toward dispelling negative stereotypes.

Placing today’s problems in historical context is revealing. When I teach African politics, I start by discussing pre-colonial Africa and the many democratic traditions that existed prior to the devastation of the slave trade and colonial occupation. In discussing colonialism, I emphasize the violence used to exert control and the ways in which European powers centralized rule, eliminated checks on state power, and established economies designed to extract wealth without providing development. In many ways, Africa still lives with these legacies of violent, unfettered rule and international economic exploitation.

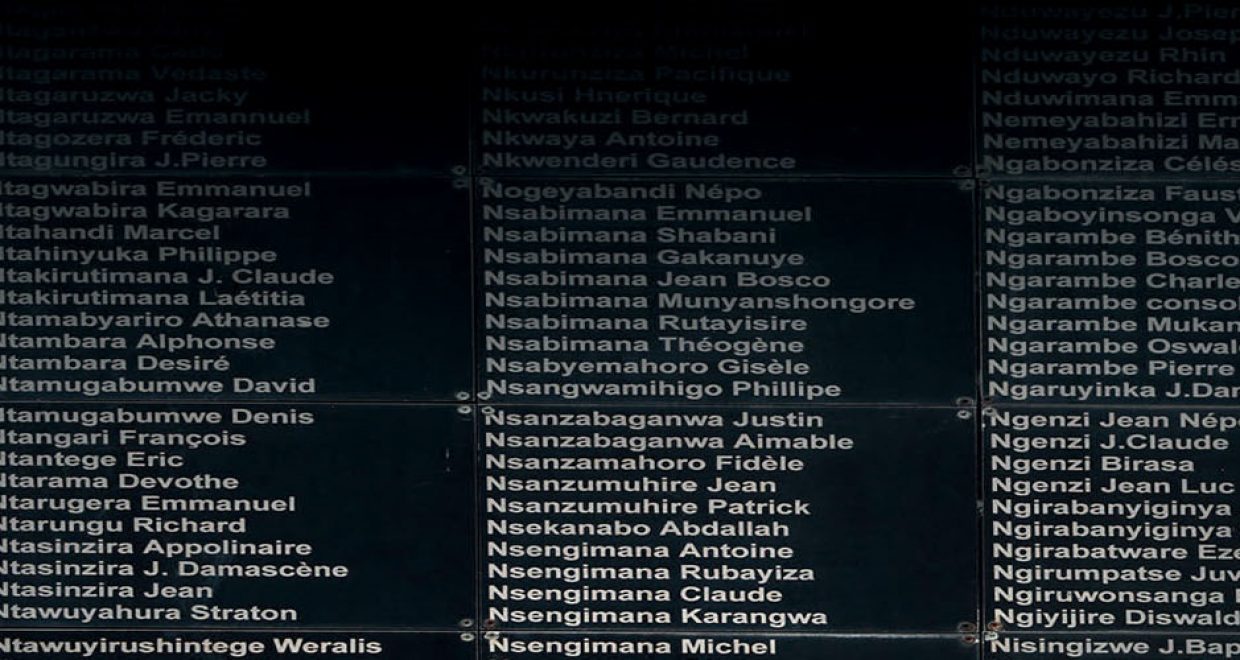

My scholarly work has focused on some of Africa’s most troubled places, but I find that exploring the causes of violence and brutal governance helps to dispel the impression that Africa is somehow prone to chaos. In my research on Rwanda, I demonstrated that the 1994 genocide was not spontaneous but instead required careful planning by national and local leaders. The international community also held some responsibility, since colonial authorities and missionaries helped to define and heighten the divisions that were at the root of the country’s social divisions, and international support – including the provision of arms and militia training – helped to make the genocide possible. Despite clear evidence that genocide was happening in Rwanda, the international community chose to withdraw rather than acting to stop the violence.

In my recently published book, Memory and Justice in Post-Genocide Rwanda, I explore the legacies of Rwanda’s genocide and the ways in which the government and the population have sought to rebuild the country. While I recognize that Rwanda’s post-genocide government is run efficiently and has managed economic development effectively, I also show that the country’s extensive transitional justice programs that supposedly promote national healing have in fact served to help strengthen the power of state authorities. The international community’s willingness to overlook human rights abuses by those now in power in Rwanda has empowered them to continue to rule in an authoritarian fashion and hampered the process of national reconstruction.

Slavery and colonialism were once justified through perspectives that denied Africans their full humanity. The attitudes recently expressed in the White House unfortunately share the same racist perspectives. By both telling Africa’s untold good news and better explaining Africa’s difficult cases like Rwanda, we as scholars can help the Western public recognize the full humanity of Africans and develop international policies based on empathy rather than racism.

Click here to read a free chapter of Memory and Justice in Post-Genocide Rwanda