Inside the DMZ: Exploring Militarized Masculinities Through Visual Autoethnography

Referencing his article in the latest issue of the European Journal of International Security, Professor Roland Bleiker examines how everyday aesthetic sensibilities can open up new ways of thinking about security dilemmas.

Over three decades ago I worked for two years as a Swiss Army officer in the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Living in this eerie borderland was fascinating, and so was the rare privilege of travelling back and forth between North and South Korea a time then the Cold War was still dominating global politics.

Fascinating as my experience might have been back then, can it be of relevance for the study of politics and security today?

I answer this question in the affirmative in the European Journal of International Security (EJIS). I draw on my experiences, and on photographs I took back then, to examine how an appreciation of everyday aesthetic sensibilities can open up new ways of thinking about security dilemmas. In so doing I build on several decades of work not only onn Korea but also on aesthetic and visual approaches to understanding politics and security.

One could call this form of inquiry visual autoethnography. A key challenges of autoethnographic research in general is to avoid self-indulgence. From a scholarly perspective, my own experiences matter only insofar as they directly illuminate the political issues at stake. The question then is: what exactly can visual autoethnography add that cannot – or not easily – be revealed through other forms of inquiry?

I argue that visual autoethnography can be insightful not because it offers better or even authentic views – it cannot – but because it has the potential to reveal how prevailing political discourses are so widely rehearsed and accepted that we no longer see their partial, political and often problematic nature.

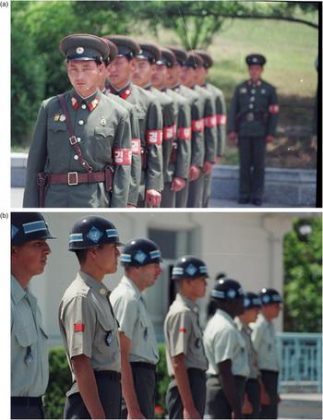

In this short blog I offer one illustration: how a self-reflective engagement with my own photographs of the DMZ reveals the deeply entrenched role of militarised masculinities that transgress the border and shape security policies on both sides.

Entering the Militarized World of the DMZ

The DMZ lies at the physical and symbolic centre of the Korean conflict. It is a four-kilometre buffer zone along the 38th parallel that keeps the two warring sides apart. Up to two million troops face each other across the border, and so do plenty of weapons of mass destruction.

I first arrived in the JSA on a late September day in 1986. In the early hours I was driven from Seoul to Panmunjom, where I took up the position of Chief of Office of the Swiss Delegation to the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission. “Keep up the fire” bellowed a young US soldier as we crossed a bridge over the Imjin river and approached the most militarized landscape I had ever seen: the so-called Demilitarized Zone. My new home turned out to be even more surreal: located right at the barbed-wired fence that divided the peninsula, our barracks were surrounded by military observation posts and loudspeakers on both sides. The latter were competing with each other every night, blaring propaganda speeches and music into an otherwise pristine and stunningly beautiful landscape.

The DMZ is one the world’s most guarded and hostile borders. Militarism paradoxically cuts right across the hermetically sealed dividing line. In the so-called Joint Security Area, the border runs through shared buildings. North and South Korean troops face each other eye-to-eye. In one way they epitomize the are extreme opposites: arch-enemies that epitomize two incompatible and diametrically opposed ideological worlds. But from a bit of distance one can see just as many similarities: they are all soldiers marching in uniform and performing the very same militarized ritual.

Militarized Masculinities and the Political Construction of Common Sense

Looking at my photographs of the DMZ today I notice one thing above all: their strikingly gendered nature. There are virtually no women in them. There are only men in my photographs. There are South Korean men, North Korean men, Chinese men. There are American men and Czech, Polish, Swedish and Swiss men. All are in uniform.

I had a hard time finding any photographs that feature women. One of the few I found was from a Military Armistice Commission meeting. The photograph sticks out because it is one of the very featuring a woman. She is not looking at the meeting room but across the border to the northern side. I wonder what she thought while surveying this all-male world.

On some level my observations are not surprising. Of course one would expect soldiers in a militarized zone and, of course, one would expect that most of them, if not all, are men.

The surprising observation about this feature has to do with my own experience and my changing relationship to my own photographs.

When I took these photographs, three decades ago, I noticed everything about the world around me, except the absence of women. When settling into the DMZ and crossing back and forth between South and North I was struck by many things I saw: the stark political differences, the cultural diversity, the militarized posture and the ideological hatred but not the most obvious feature: the absence of women.

As a military officer, and having growing up in a patriarchal society, the discourse of militarized masculinity was so omnipresent and naturalized that I simply accepted it at face value: as how things were meant to be, particularly in the DMZ. I was drafted into the army at 18 and, in an all-male environment, was trained how to march, salute, fire a gun, throw a hand-grenade and drive a tank. I was taught how to execute orders and obey, but not how to think critically, and particularly not about gender issues. Militarized values had been normalized and I accepted them as common sense without questioning – or even being aware – of the political values they entailed.

I now look back in bewilderment at my inability to see the obvious: the highly gendered nature of politics in the DMZ.

This is precisely where the links between power and militarization are at their most effective: in the construction of common sense, in societal discourse that define what is accepted as normal and not, even if this construction is based on highly partial, exploitative and problematic foundations.

What Can Visual Autoethnography Add to Our Understanding of Security?

Visual autoethnography can provide political insights though self-reflective accounts of our own experiences. It is the confrontation with visual evidence that, for me, made me realize most acutely how my own positionality reflected political dynamics that were so naturalized for me – and I presume many men around me – that I did not even recognize them.

The fact that three decades had passed since I took the photographs adds, rather than subtracts, from the potential of visual autoethnography. It is, in fact, the elapsed period of time that provides the opportunity of insight, for it is the very changing relationship between me and my photographs that reveals the power of discourse to construct and mask power relations.

My experiences, and my relationship with my own photographs, show how the political consequences of the gendered and militarized nature of the DMZ go far beyond the immediate and obvious: men in uniforms, surveillance installations, barbed-wire.

Militarized masculinities are part of broader societal values. They shape the core of the Korean conflict, from its origin to current political dynamics. My entire experience in Korea was gendered, revealing what feminist scholars have pointed out for long: the need to understand that militarized masculinities are highly political because they permeate all aspects of society, from the everyday to foreign policies. They are located and gain political significance in the clothes we wear, the films we watch, the national anthems we rehearse and the security policies we deem urgent and compelling.

Militaristic ways of thinking become elevated to the prime and seemingly most reasonable and compelling manner to address security issues. The result is that certain individuals, and the values they espouse, are given greater authority to comment on – and take decision about – questions of security. This hinders both adequate scholarly understanding and the search for innovative policy solutions.

This where the power of visual autoethnography lies: in its ability to reveal how prevailing ways of seeing, thinking and conducting security politics are so deeply entrenched and taken-for-granted that their often problematic nature is no longer recognized, yet alone discussed and addressed.

– Roland Bleiker, Professor of International Relations at the University of Queensland

– Professor Bleiker’s EJIS article is now available free of charge until the end of April 2020.

– His research explores the political role of aesthetics, visuality and emotions, which he examines across a range of issues, from security, humanitarianism and peacebuilding to protest movements and the conflict in Korea. Previously he worked in the Korean Demilitarized Zone as Chief of Office of the Swiss Delegation to the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission. Bleiker’s books include Popular Dissent, Human Agency and Global Politics (Cambridge University Press 2000), Divided Korea: Toward a Culture of Reconciliation (University of Minnesota Press 2005/2008), Aesthetics and World Politics (Palgrave 2009/2012) and, most recently and as an editor, Visual Global Politics (Routledge 2018).