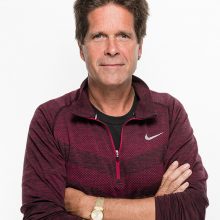

Meet the Editors: Q&A with Professor Andrew Hemphill, Editor for Parasitology

Welcome to our “Meet the Editors” series, where we interview the editorial team about their work and their relationship to the journal. In this post we meet Professor Andrew Hemphill, Editor for Parasitology

What is your current job title both within Parasitology and outside of the journal? Where are you based in the world?

I am Associate Professor and have a group leader position at the Vetsuisse Faculty of the University of Bern, where I am also partially involved in teaching Parasitology to undergraduate students. Originally, I had studied Microbiology at the same University, but with emphasis on cell and molecular biology. I did my MSc in 1988 and completed my PhD on the structural and molecular composition of the trypanosome cytoskeleton in 1991, so I was exposed to protozoan parasites early on. I spent one year of my PhD at the Biology Department of the University College in London learning and applying different electron microscopical techniques, and after my PhD I stayed another 2 years at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine as a post-doc, but with independent funding. I returned to Bern to join the Institute of Parasitology in 1994, obtained a permanent position there a few years later, and stayed there since then. I joined the editorial board of Parasitology in 2008, and Stephen Phillips recruited me as one of the editors for the journal in 2010. I have strong ties to a number of researchers around the world, including Spain, Portugal, the US and Argentina.

In a few sentences, please describe the focus of your work. Which parasites do you study? What is the goal of your research? What approaches do you use in your work?

I have worked on a number of parasites during my professional life. I started out with Trypanosoma brucei, the causative agent of sleeping sickness in Africa. During my MSc and PhD I was involved in studies on the cytoskeleton of these parasites, most notably in the identification, purification and characterization of microtubule associated proteins. The cytoskeleton of these parasites is mainly microtubule-based and we hypothesized that proteins that mediate the unusual stability of the cytoskeleton could be relevant targets for chemotherapeutical approaches. Work on trypanosomes continued during my post-doc time at the LSHTM. I was lucky to have gotten my own funding for this, studied how Trypanosoma congolense bloodstream forms interact and adhere to bovine endothelial cells, and identified sialic acid as a main host cell surface receptor.

Once I started in Bern in 1994, I developed an in vitro culture system for the metacestode stage of Echinococcus multilocularis, a cestode parasite that is also prevalent in Switzerland and the surrounding countries, and we soon realized that this is an ideal model to (i) study proteins involved in host-parasite interactions, and (ii) novel therapeutic options and drug targets. This model has been much improved by others, and is now widely applied. In parallel, I maintained a keen interest in protozoan parasites, and since during this time Neospora caninum and neosporosis was arising as an economically important cause of abortion in cattle, this was a great opportunity to enter the field of apicomplexans. Here, we focused on novel vaccine candidates and potential therapeutic approaches, and expanded also to other relevant apicomplexans infecting food animals including Toxoplasma and Besnoitia. This has now clearly become my main focus of research, which involves cell biological, molecular and biochemical approaches. In addition I have been on several grant funding committees, and I am member of the Veterinary Medicines Experts Committee of Swissmedic, the Swiss medicines licensing agency.

When did you first become interested in parasitology as a field? Did a particular teacher or mentor direct your career path?

To be honest, up to the time I was about 20, I never thought I would be a biologist, and surely not a parasitologist. I somehow started studying biology because I didn’t really know where to go after school, and the only subject I had top-grade was biology. So I embarked in Biology studies at the University of Bern. However, I did have two important mentors, who somehow directed me to where I could or should go. One was Thomas Seebeck, at the time Professor for Cell Biology at the University of Bern. He gave fantastic lectures on molecular and cellular biology, and it was clear to me that I wanted to join his research group for a MSc and later a PhD. He made it possible for me to pursue my interest in electron microscopy in London, and supported me also during the later stages of my career, with good advice and friendship. Thanks to him and his guidance, I knew exactly where I wanted to go after my PhD, namely to pursue academic research and have my own research group. The other very important person is Simon Croft at the LSHTM, who gave me labspace and incredible support 1992-1994, and has stayed a friend throughout all these years. Thanks to him my stay at the LSHTM became an eye-opener, and I got an insight into the fascinating variety of parasites, and the different ways they manipulate and interact with their host. I decided that this would be a great thing to pursue in the future.

How did you first become familiar with Parasitology?

In 1994, Parasitology published my first paper written entirely by myself, without any supervisor involved. I was in England at the time, so Parasitology was an obvious choice. The paper described in detail the interaction between Trypanosoma congolense with bovine aorta endothelial cells. The editor-in-chief was Frank Cox, he was very supportive, made great suggestions for improvement of the manuscript, and this was an overall very positive experience. When I was back at Bern University, it was clear for me that my first paper on how Neospora caninum interacts and invades host cells would also be published in Parasitology.

What motivated you to become an editor at Parasitology?

I was first asked by Stephen Philipps to become member of the editorial board in 2008, which I happily did, since this was anyway my favorite journal. In those days, there were also real editorial board meetings taking place, mostly in London, where discussions were held and decisions were made on how the journal should go forward, and I liked to be part of a team that would take responsibility rather than just being a name on a list of people. In 2010 Parasitology changed, and adopted the current scheme with one editor-in-chief, one editor for special issues, and another five editors taking responsibility for manuscript handling. Of course, I was very happy to be asked to be a member of that team and did not hesitate.

What is the best part of editing for Parasitology?

Since I am editing for Parasitology, I have encountered many subject areas and research fields that I have not been familiar with, and this has really given me a lot insights I would not have gotten otherwise. I have a keen interest in many different aspects of the biology of parasitism, and I like the broad scope of the journal. In addition, I particularly enjoy when I succeed in getting good specialist reviewers, who actually want the help the authors with constructive criticism rather than ripping their data apart. If this then leads to a markedly improved manuscript, ready for acceptance, I am particularly pleased. I also enjoy very much to interact on a personal level with my editor colleagues, the team at Cambridge University Press, and also with authors and reviewers. Lastly, to be a part of a journal that has been around for over a hundred years makes me proud.

Do you have any advice for those submitting to Parasitology?

There are several pieces of advice, which all adhere to the principal that there is no second chance for a first impression: make sure that the experiments you describe are reproducible; prepare your manuscript carefully; have it read and corrected by all co-authors; stick to the instructions for authors; try to avoid typographical errors, and make suitable reviewer suggestions. Suggest reviewers that are specialists in the field, they do not have to be your friends. Do not take criticism personally, take it as a means to improve your manuscript. And if your manuscript is rejected despite all efforts, don’t be disappointed. Parasitology simply cannot publish all manuscripts that are submitted, so certain criteria must be applied.

What advice would you give to early career researchers who are just starting out in parasitology as a field?

I meet quite a lot of young researchers that finalize their PhDs and then don’t really know what they want to do. They slide into the track of being a post-doc rather than actively pursuing their goals. When it comes to make decision for the future, it is clearly easier to decide if you are sure about you want to do in your professional life. And also think about whether this is compatible what you expect from your private life. The maintenance of a healthy work-life balance is essential, and this balance might differ depending on the individual needs. Life as a researcher, especially in academia, can be rewarding, but also one has to be able to deal with a high level of frustration. If you decide to go follow this track, choose your work place or group you want to join carefully, and aim to publish in high-impact papers.