Paths towards Coalition Defection: Democracies and Withdrawal from the Iraq War

Drawing upon his Open Access article in vol.5, no.1 of the European Journal of International Security, Patrick A. Mello explores the withdrawal of democracies from the Iraq war as a form of coalition defection.

In April 2004, Spanish Prime Minister José Zapatero announced his country’s immediate withdrawal from the US-led military coalition that had been formed for the Iraq War. The ‘coalition of the willing’ has been associated primarily with those countries that deployed combat forces for the invasion of Iraq in March 2003 (the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Poland). What has received less attention is that over the course of its operation, the ‘Multinational Force in Iraq’ (MNF-I) contained 29 democracies that joined the United States in Iraq.

On the face of it, Zapatero’s decision reflected what political scientists would expect: a newly elected leader reassesses an unpopular policy and opts for a reversal. Zapatero’s decision to withdraw also made good on a campaign pledge. Moreover, as Zapatero was the leader of the Socialist Party (PSOE), this resonated with expectations about leftist parties being critical towards military engagements, especially when these are conducted without UN authorization and outside of alliance frameworks, such as the preventive war against the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq.

There were other cases with similar characteristics. In Australia, newly elected Prime Minister Kevin Rudd of the Labor Party announced that he would withdraw the country’s combat forces from Iraq. Likewise, governments in Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, and elsewhere, with governments that had been steadfast supporters of the Bush Administration, at some stage decided to end their military involvement in Iraq. Yet, others maintained their deployments and some even enlarged their commitment. Poland continued its military presence despite changes in the political leadership and partisan composition of government. South Korea upheld and increased its deployment, becoming the third largest troop contributor after the United States and the United Kingdom.

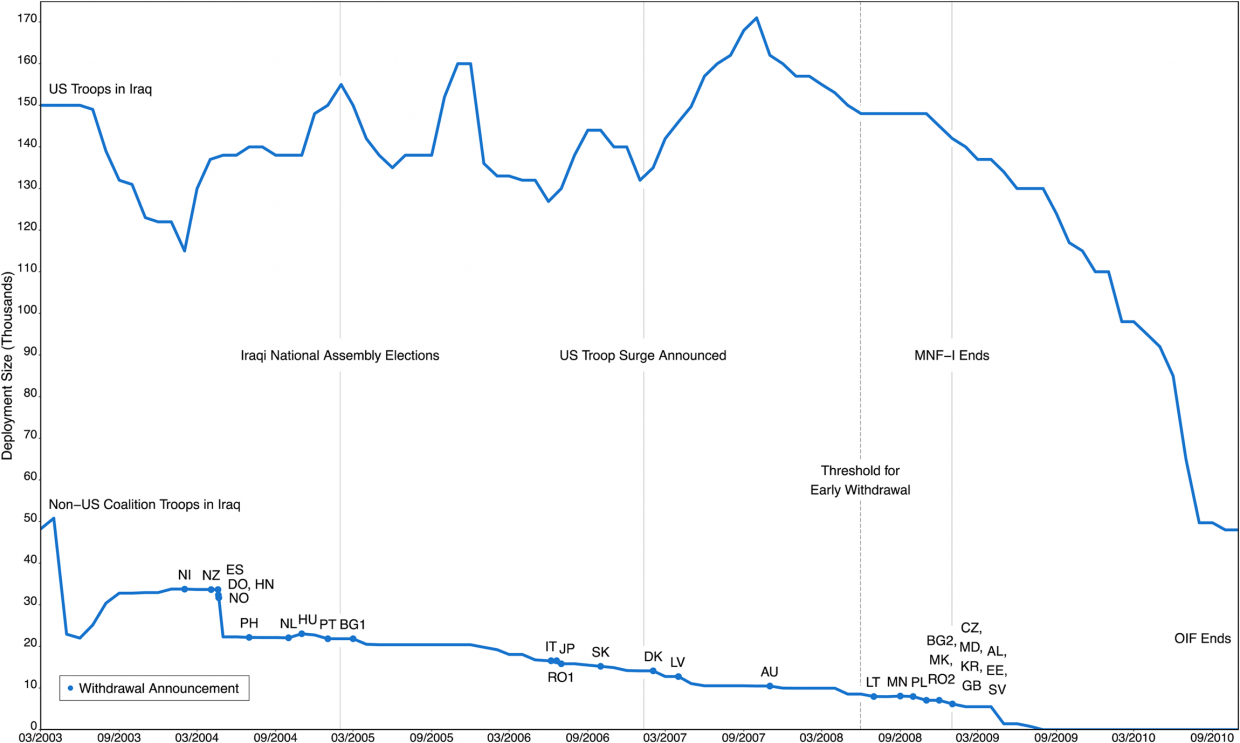

Over the course of the Iraq War, 18 out of 51 democratic leaders from 29 democracies withdrew their countries’ forces from the military coalition, whereas 33 leaders decided to continue their military engagement. Figure 1 shows a timeline of US and non-US troops in Iraq with blue dots marking individual countries’ withdrawal announcements (see the article’s Appendix for a case-by-case listing). We can see that a first batch of countries starts to withdraw in March 2003, one year after the invasion, while a second batch leaves the coalition from mid-2006 onward. Yet, a large group of countries stays until the end of coalition operations.

In my article, I develop an integrative explanatory model to account for the observed variation among democracies. Using fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA), the study entails five explanatory conditions: leadership change, upcoming elections, leftist government, coalition commitment, and civilian and military casualties in Iraq. It is the first study of the Iraq War that examines coalition withdrawal across all of the involved democracies, differentiated at the level of individual leaders and for the entire timeframe of operations (2003–2010).

The results show the existence of multiple paths towards coalition defection. They also entail some counterintuitive findings. While prior work suggests that leadership changes and upcoming elections are driving factors behind withdrawal decisions, I show that most of the observed cases are actually not captured by such dynamics. Three results stand out: (1) leadership change only led to withdrawal when combined with leftist partisanship and the absence of upcoming elections, (2) fatalities and coalition commitment played larger roles than previously assumed, and (3) coalition defection often happened under the same leaders who had made the initial decision to become involved in the Iraq War, and who did not face elections when they made their withdrawal announcements.

The findings contrast with studies that identified a statistically significant relationship between leadership change and coalition withdrawal and studies that underscored looming elections as an important driver of withdrawal decisions. However, I show that for the Iraq War, withdrawal decisions were made predominantly by leaders who did not face elections. Likewise, 64% of the new leaders continued their country’s Iraq deployment. In other words, a large number of withdrawal decisions were made by incumbents who were also responsible for their country’s involvement in Iraq.

I argue that these cases can at least be partially explained when looking at leaders’ domestic situation. Many of the culpable leaders later faced severe domestic opposition because of the deteriorating situation in Iraq. Those leaders who authorized withdrawal, did so at a time when there was still a comfortable distance to the next election. Taking the unpopular Iraq War issue off the political agenda, these leaders arguably strengthened their own domestic political position. In that sense, electoral calculations may have weighed in, but they were outside the timeframe that is typically taken into account when measuring electoral incentives.

In sum, my article provides empirical evidence of the political dynamics that govern wartime coalitions among democracies. In that sense, the study also contributes to some long-standing IR debates about democratic reliability and democratic responsiveness in foreign policy. Further research may show, for instance, whether dynamics similar to those identified in Iraq were at play during NATO’s ISAF mission in Afghanistan or whether leader behavior resonates with certain configurations of personality traits.

– Patrick A. Mello is Visiting Scholar at the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy, University of Erfurt, Germany.

– The Open Access article can be freely accessed from the EJIS website.