Be Prepared to Impress: Interwar Hungarian Cultural Diplomacy and the Fourth World Scout Jamboree of 1933

This accompanies Zsolt Nagy’s Contemporary European History article ‘The Race for Revision and Recognition: Interwar Hungarian Cultural Diplomacy in Context‘

In August 1933 25,000 young boy scouts from over fifty countries gathered in the small Hungarian town of Gödöllő – just twenty-some miles north-east of Budapest – to celebrate the Fourth World Scout Jamboree. After welcoming speeches from the Hungarian Regent Miklós Horthy and from the founder of the Scout movement Robert Baden-Powell, the scouts embarked on two weeks of camping, water- and air shows and various other excursions and activities.

Source: International Scouting Museum

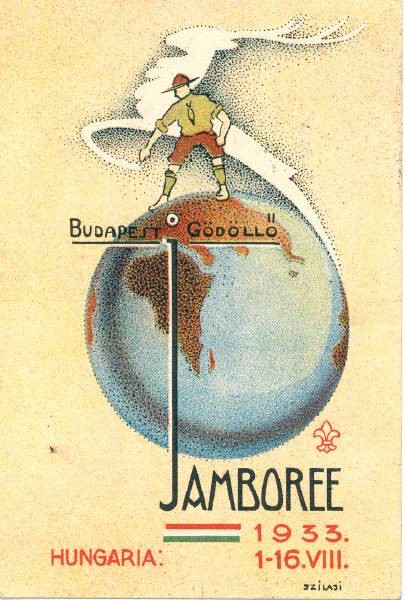

Why would a small, cash-strapped country invest money, at the height of the Great Depression, to host such an event? The answer, as I show in my article in the new special issue of Contemporary European History, is that this event was designed to boost Hungary’s international image as part of an ambitious cultural diplomatic campaign led by the Hungarian government. The poster produced for the event clearly depicts the hopes and aspirations of the organisers. The legendary White or ‘Miracle’ Stag, a Hungarian national symbol that served also as the symbol of the Jamboree, stands on top of the world: Hungary, at least temporarily, would be at the centre of the world’s attention. The positive media coverage that the event received convinced the organisers that the Jamboree had achieved its goal.

Could such an event really make a difference on the international stage? Could it support Hungary’s effort to revise the post-war Treaty of Trianon, which had stripped the pre-war kingdom of so much territory and population? The architects of Hungary’s interwar cultural diplomacy certainly believed that it could. The basic assumption behind Hungarian cultural diplomatic efforts was the belief that the punitive Treaty of Trianon had been the result of the country’s tainted image – an image that suffered from the fact that Hungarian achievements and contributions were generally unknown beyond the nation’s borders. The Hungarian elite were anxious to cultivate a positive image abroad and they were prepared to spend a good deal of money to achieve it. However, the Hungarians were not alone in hoping to use cultural means to gain international support for their foreign policy agenda. On the contrary, other East and East-Central European nations, with similarly limited economic, political and military power, also hoped to win over the hearts and minds of the international community. The resulting race for recognition in interwar East-Central Europe is the topic of my article.

In it I show that Hungary’s political leadership responded to this intensely competitive climate not only by trying to enlighten the international community about the historical and cultural deeds of the Hungarian nation; they also aimed to prove Hungary’s supposed cultural supremacy over its regional rivals. Examining the way Hungary pursued these goals through domestic and international festivals, including the 1933 Scout Jamboree as well as the 1930 celebrations of Saint Emeric and the 1937 Paris World’s Fair, my article explores the utility, but also the limitations, of small power cultural diplomacy in an age of great power politics.

Read all articles in the collection

Main image credit: Postcard from Fourth World Scout Jamboree, Gödöllő, Hungary, 1933 Source: International Scouting Museum