Locke, Toleration and Political Participation – A New Manuscript

This accompanies J. C. Walmsley and Felix Waldmann’s Modern Intellectual History article John Locke, Toleration, and Samuel Parker’s A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie (1669): A New Manuscript

Locke’s arguments for toleration are well-known and immensely influential. Less well-known, but of equal import to his worldview, are the exceptions he made to these arguments for religious freedom.

In 2019, we published a previously unknown manuscript by Locke, the Reasons for tolerateing Papists equally with others from 1667, which showed Locke formulating his earliest thinking on toleration in such a way as to exclude Catholics. His Essay concerning Toleration,written immediately afterwards, and likely inspired by the Reasons, expanded upon these initial arguments. For Locke, Church and State were separate and – so long as religion didn’t foment sedition – people could worship God however they chose.

Our new recent article presents the discovery of another entirely unknown manuscript by Locke – “S Parker on Toleration” – located in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

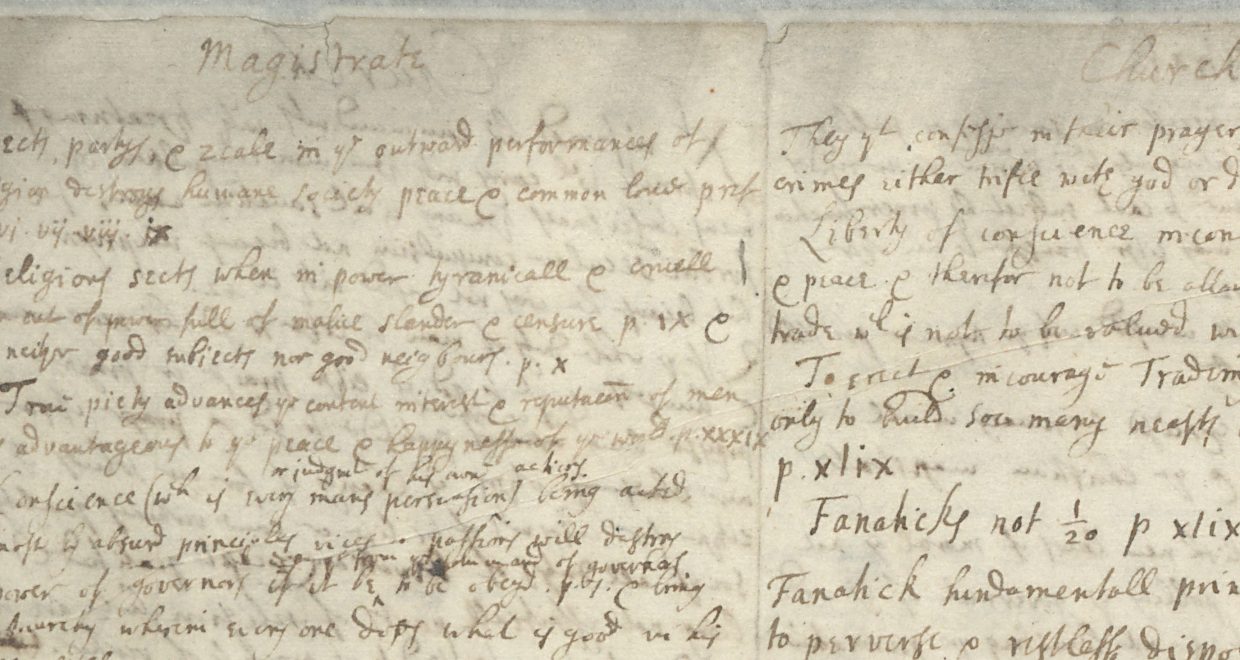

In 1669, the clergyman Samuel Parker published A Discourse of Ecclesiastical Politie arguing that people were free to believe whatever they liked, but that the magistrate should control the “outward Practices” in religion to maintain civil peace. This cut to the heart of Locke’s arguments in the Essay concerning Toleration. The newly recovered manuscript comprises 3,000 words of Locke’s notes and queries on Parker’s Discourse, separated into two columns to reflect his division between “Magistrate” and “Church”.

Locke thought Parker’s distinction is unworkable: you can’t separate conscience from worship in the way Parker pretends. “He sets noe bounds to conscience how far it is or is not to be tolerated”, Locke writes, so how can we draw the line between inward belief and outward conformity? Locke asks, “what becomes of those things I judg unlawfull?” How can I acquiesce in outward actions that violate my beliefs about what God would want me to do?

But Locke does not reject every component of Parker’s argument. Parker held that religion played a foundational role in society:“without it the most absolute and unlimited Powers in the World must be for ever miserably weak and precarious, and lie always at the mercy of every Subjects Passion and Private Interest.” Locke transcribed Parker’s wording in the new manuscript and then expanded upon it in a Query: “whether this extends any farther then a beleife of god in general. but not of this particular worship”? Locke believed God would account for your worldly conduct in afterlife. This fear of divine punishment would serve as a guarantee of morality. Thus, a “minimalistic theism” must underpin any political society, and Locke’s argument for toleration – belief in God in general, not a specific religious practice, is sufficient.

However, this “minimalistic theism” has a clear corollary: non-believers would have no fear of divine punishment and no hesitation to violate the dictates of morality. This is exactly what Locke asserted in additions made to his Essay concerning Toleration just a few months later: without “beleif of a deitie … a man is to be counted noe other then one of the most dangerous sorts of wild beasts & soe uncapeable of all societie.” Locke would make similarly pointed assertions about atheists in his1689 Letter concerning Toleration. This newly discovered manuscript shows Locke formulating this strict limit to his toleration for the first time. The discovery thus fills an important gap in the history of Locke’s thinking on toleration – we can now see when and how Locke came to exclude atheists from political participation.