‘The most important time in your life’: quotations in recent science

This accompanies Nick Hopwood’s British Journal for the History of Science article ‘Not birth, marriage or death, but gastrulation’: the life of a quotation in biology

‘We are what we quote’, wrote literary scholar Gary Saul Morson, so heavily do we depend on the words of others. In academia, as in everyday life, attributed quotations serve more specifically to enlist support and supply evidence, to amuse, encapsulate, impress, inspire and oppose. Medics still quote Hippocrates and William Osler, but it is widely assumed that natural science, with its unsentimental commitment to innovation, has confined quotation to anthologies, epigraphs and after-dinner speeches. Today’s scientists are not eloquent enough, and anyway, primary research articles in biology or physics have no space for direct, demarcated quotations. My own article challenges this view by reconstructing the making and uses of a dictum that has figured in science communication from teaching through public engagement to research.

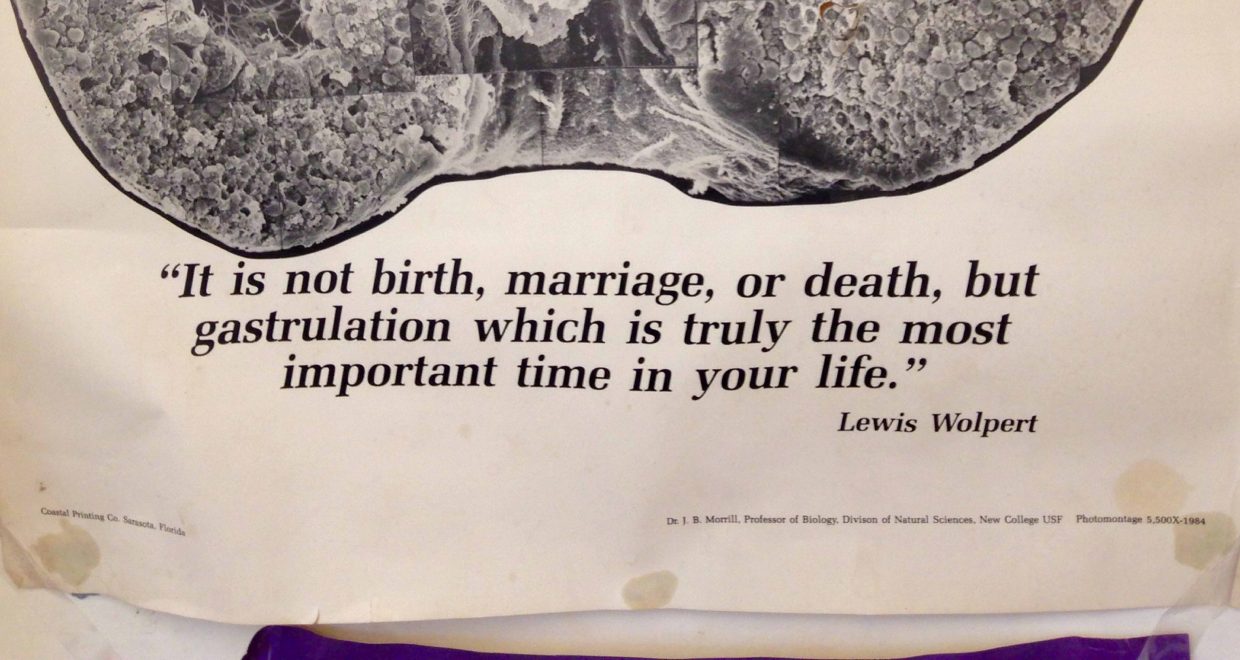

I chose the most famous quotation in developmental biology: ‘It is not birth, marriage or death, but gastrulation which is truly the most important time in your life.’ What, we are invited to ask, is gastrulation? Answer: it is the processes early in animal development that turn a ball of cells into a three-dimensional body with the main parts in more or less the right places. Credited to the developmental biologist Lewis Wolpert, the aphorism represents embryologists’ habit of asserting that we are never again as interesting as we were months before birth.

I had long wanted to investigate this professional bias, but put it off. Then Wolpert died in January 2021 and, as developmental biologists tweeted his quotation, I thought: now or never. I had heard what a few insiders knew—Wolpert did not originate the whole sentence—but mine is no story of misattribution. I reconstruct how it took a global village to raise a quotation that channelled prior claims for ‘the most important moment’ through the culture of developmental biology. I also show that this was attributed to him as soon as it became a quotable phrase.

The United Kingdom being in lockdown, I moved electronically between scientists who sent me reminiscences and photos, archivists who equally generously scanned manuscripts, and the databases that have revolutionized such work. My virtual journeys tracked the shifts by which Wolpert’s bon mot took shape. It began as a quip at a workshop dinner in Belgium in 1979. It gained its definitive form in a monograph by his colleague Jonathan Slack, who lured readers by adding the contrast to major life events. And it took off on a poster of a sea urchin gastrula produced from an undergraduate project in Florida. As winter turned to spring and the travel bans continued, I fantasized about eating restaurant food in Antwerp and diving for urchins in Sarasota Bay.

The quotation kept transporting me to places historians of science rarely visit, and encounters with media we seldom study, because it has found so many uses. Juxtaposing a technical term with recognizable events intrigued readers and listeners, while the initiated enjoyed the joke that the supposedly most important time is over before you even know it. Though some favoured other stages or balked at the exaggeration, the dictum owes its success to this doubling as expository tool and marker of professional identity. It is a fixture of undergraduate lectures that has featured often in newspapers and popular-science books, once even a cabaret, as well as research seminars and the odd journal article. The history I tell in mine exemplifies how indispensable quotations can become—also in recent science. They invoke tradition, generating a sense of belonging and inspiring the young, and are involved in innovation, too. Wolpert’s has recently been enrolled to argue for an extension of the 14-day limit on human-embryo research.

Read the full Open Access article

Main Image: Detail from a poster (shown in full in the article) of a montage of scanning electron micrographs of a sea urchin gastrula by John Morrill, based on a project by Laurinda Santos, printed by Coastal Printing of Sarasota in 1984 and photographed by Lewis Wolpert on his kitchen door in London in 2015.

More from Nick Hopwood: