Circe’s Etruscan Drugs

When only four words of a poet’s entire output in a specific genre survive to the present day, is there really anything of substance that we can say about this poetry on the basis of such slender remains? In this new blog, Jessica Lightfoot adds further context to research recently published open access in The Classical Quarterly.

It is a problem faced by anyone who wishes to pursue the several tantalising testimonia concerning Aeschylus’ elegiac poetry that have come down to us from antiquity. Though famed today for his tragedies alone, there is evidence that the Athenian poet was known for a broader literary oeuvre in antiquity. The only certain non-tragic Aeschylean fragment remaining to us, however, is both frustratingly terse and puzzlingly enigmatic: “of Tyrrhenian descent, a drug-making nation …” The brevity of this fragment has deterred investigation into Aeschylus’ elegies. But an examination of the broader text within which these words are buried, as well as a consideration of other scattered references to Aeschylus’ non-tragic poems, reveals that there is much more that we can say about his elegies than previously realised.

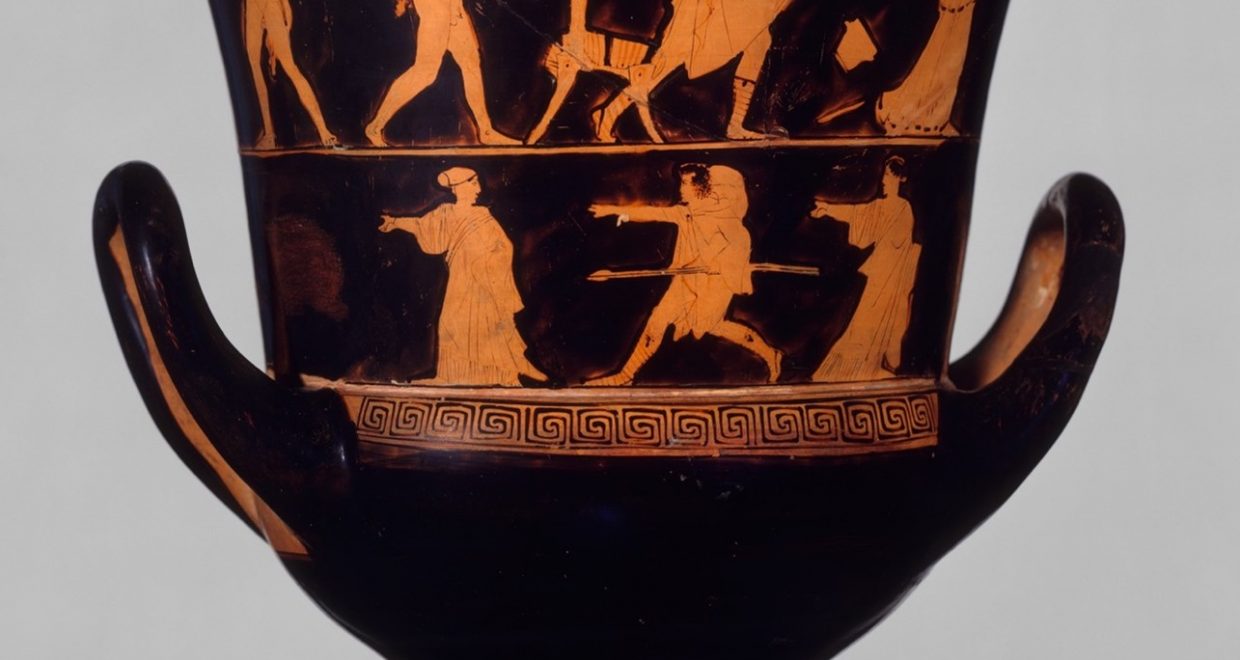

This Aeschylean elegiac fragment is found in Theophrastus’ Historia Plantarum, a fourth-century BCE treatise about the types and uses of plants and herbal medicines. If we examine the broader Theophrastan passage in which the fragment is embedded it becomes clear that Aeschylus’ words are being used as evidence in a complex argument which connects Homer’s Circe, and the powerful drugs which she uses to transform Odysseus men into swine, to Tyrrhenia in Italy, the home of the Etruscans. This connection is also found in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History in a passage which uses the same Aeschylean poem as evidence for Circe’s association with Italy. Circe’s homeland of Aeaea is not mapped onto a real-world Italian location in Homer’s poetry, though this localisation appears later in the Greek literary tradition, most notably at the end of Hesiod’s Theogony. By carefully examining both the passages of Theophrastus and Pliny in which Aeschylus’ words are mentioned, it is clear that his original elegiac poem also refers to Circe’s localisation in Italy, and to her status as the supposed ancestor of the Etruscan people as the mother of Agrius, Latinus and Telegonus, three Italian sons purportedly born to Odysseus. Aeschylus’ elegiac fragment is thus the earliest text we have that links Circe’s drugs to Italy, and one of the very earliest extant references linking Odysseus’ famous travels to the Italian mainland. As such, it presents us with crucial and hitherto unappreciated early evidence concerning interactions between Greeks and non-Greeks in the western Mediterranean.

Aeschylus’ elegiac interest in Circe and the Etruscans is significant for one further reason. We know that Aeschylus spent time working in Sicily and produced work for the Syracusan tyrant Hieron I, a ruler famous for his patronage artistic productions which praised his political and military exploits. One such exploit was his victory over the naval forces of the Etruscans at the battle of Cumae in 474 BCE. Hieron seems to have encouraged comparisons between this military triumph and the famous victories of the Athenians in the Persian Wars, as we can see from Pindar’s praise of the Syracusan’s vanquishment of his Etruscan foe in Pythian 1. We know that Aeschylus also produced work which supported Hieron’s cultural projection of power, most notably Women of Aitna, a play which celebrated the Syracusan’s foundation of a new Sicilian settlement. Given Aeschylus’ strong connection to this Syracusan cultural context it is thus possible that the elegy from which our fragment comes was produced for Hieron, and that its mention of Circe and the Etruscans somehow relates to the tyrant’s victory over this people at Cumae in 474. If this hypothesis is correct, Aeschylus’ few surviving elegiac words are an even more significant piece of evidence relating to early interactions between Greeks, Sicilians and Etruscans in the western Mediterranean than has been previously recognised.

The article CIRCE’S ETRUSCAN PHARMAKA: RECONSIDERING A FRAGMENT OF AESCHYLEAN ELEGY (FR. 2 WEST) is available open access on Cambridge Core.