Painting a poetic portrait

Michael Squire, Reader in Classical Art at King’s College London, introduces the picture-poems of Optatian, composed in the early fourth century AD, which are the subject of his forthcoming article ‘How to read a Roman portrait? Optatian Porfyry, Constantine and the uultus Augusti’, to be published in Papers of the British School at Rome later this year

Classicists can be terribly opinionated creatures. Whether discussing visual or literary artefacts, scholars have long taken on the task of quality control, declaring which are ‘good’ and which are ‘bad’. Those works generally agreed to be ‘good’ form the basis of the classicist canon. ‘Bad’ works, on the other hand, fall into obscurity – rarely to be read, looked at, or even referred to….

The works of Optatian (‘Publilius Optatianus Porfyrius’) very much to belong to the latter category. Optatian was a Latin poet of the early fourth century AD: writing under the emperor Constantine, he provides one of our most important sources for the cultural outlook of the 310s and 320s, and many of his poems address the emperor himself. But Optatian’s works have won little favour over the last two centuries. Like other ‘late-antique’ writers, his poems have been said to ‘pay witness to the decadence of an art and a culture’ (Raby); in the words of the most important classical reference-work (Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft), Optatian is the ‘author of hare-brained frivolities in verse’.

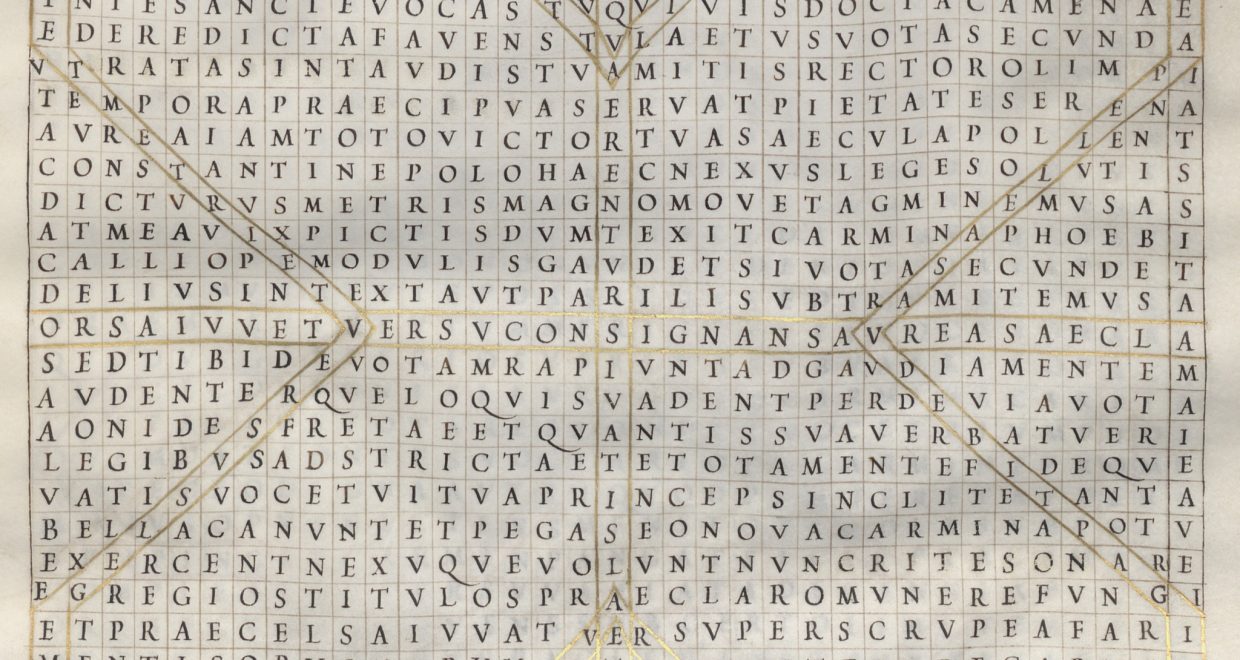

Over the last couple of years, working through the corpus of poems attributed to Optatian, I’ve tried to challenge this dismissive rhetoric. What’s so special about this corpus, in my view, is the way in which Optatian probes the iconic potential of language: many of his works are laid out in poetic grids, integrating ‘pictures’ within their poetic forms. At the same time, the constituent letters of those pictures can themselves be read as poems – they provide ‘paratextual’ compositions, commenting on the images hidden within.

In my PBSR article I explore one particular case study (Fig. 1): a poem, laid out in a grid, that purports to visualize a portrait of Constantine, sketching the ‘countenances of the emperor’ (uultus Augusti). From a classical archaeological perspective, I was first interested in what the poem might tell us about fourth-century attitudes towards painted portraiture: after all, Optatian himself declares that his creation outstrips the most famous painters of antiquity (‘it will dare outdo the waxes of Apelles’, uincere Apelleas audebit pagina ceras). But as I puzzled over the poem, I became more and more concerned with the actual form of the picture – the way in which it eschews mimetic modes of representation, rendering Constantine’s uultus a geometric pattern. My article sets out to explain the various paradoxes from which Optatian’s work is spun, thinking about this poetic ‘picture’ against the backdrop of Constantinian portraiture (e.g. Fig. 2). But the article is also an attempt to explain Optatian’s abiding fascination with the limits of ‘seeing’ and ‘reading’ – and to sketch a more complex picture of Optatian than scholars have tended to assume…

Michael Squire’s full article will be published in volume 84 of Papers of the British School at Rome in October 2016.

Sign up for content alerts or follow us on Facebook and Twitter to be the first to know when the article is published.