Q&A with Barbara Keys: Meet the Editorial Board for Modern American History

For the latest entry of our blog series introducing the board members of the new Cambridge University Press journal, Modern American History, Barbara Keys shares her thoughts on the field and on teaching American history in Australia.

Barbara Keys is Associate Professor of U.S. and International History at the University of Melbourne. Her most recent book is Reclaiming American Virtue: The Human Rights Revolution of the 1970s (Harvard University Press, 2014). Current projects include a study of moral claims in global sports events, the role of personal diplomacy and emotions in international relations, and Henry Kissinger and Sino-American relations since 1971.

Why do you study modern American history and not something else?

Why do you study modern American history and not something else?

The United States is a country of dizzying contradictions, from the founding sin of slavery in a “free” country to the election of a billionaire populist today. I teach in Australia, and my Australianist colleagues lament that students here aren’t interested in Australian history because they find it dull. But they find U.S. history full of drama—as indeed it is. It’s a country of great diversity and wild extremes. It’s endlessly fascinating and full of thorny knots to untangle.

What are some of the challenges facing the field today? In what new directions might the field go?

In That Noble Dream, Peter Novick recalls that for his doctoral qualifying exams, he simply read every book in his field. Those days are long gone. “The field” is now not so much a single field but many interrelated subfields, and the sheer quantity of scholarship is a challenge for all of us. We often talk about the difficulties of synthesis that these conditions have created, but it’s a problem for our work no matter what we’re doing: there is always a lot more you could read.

The conditions in which we work are increasingly stressful. Employment in the academy has become precarious for many people, history enrollments are in decline, and the relevance of the humanities is increasingly questioned. These pressures are not unique to U.S. historians, but future historians studying developments in our field will no doubt point to these external pressures to help explain why the field evolved in certain directions.

I’m not going to point to topics or methods that are now or could become trendy—it’s often best to avoid fads! Instead I’ll note that often some of the most useful work happens when scholars take something that has become part of the landscape—an interpretation that gets repeated so often that it assumes the status of fact—and pick it apart to show that it’s based on false or questionable assumptions. It’s so important to periodically challenge our assumptions.

If you could have been present in any “room where it happened,” what would you have witnessed?

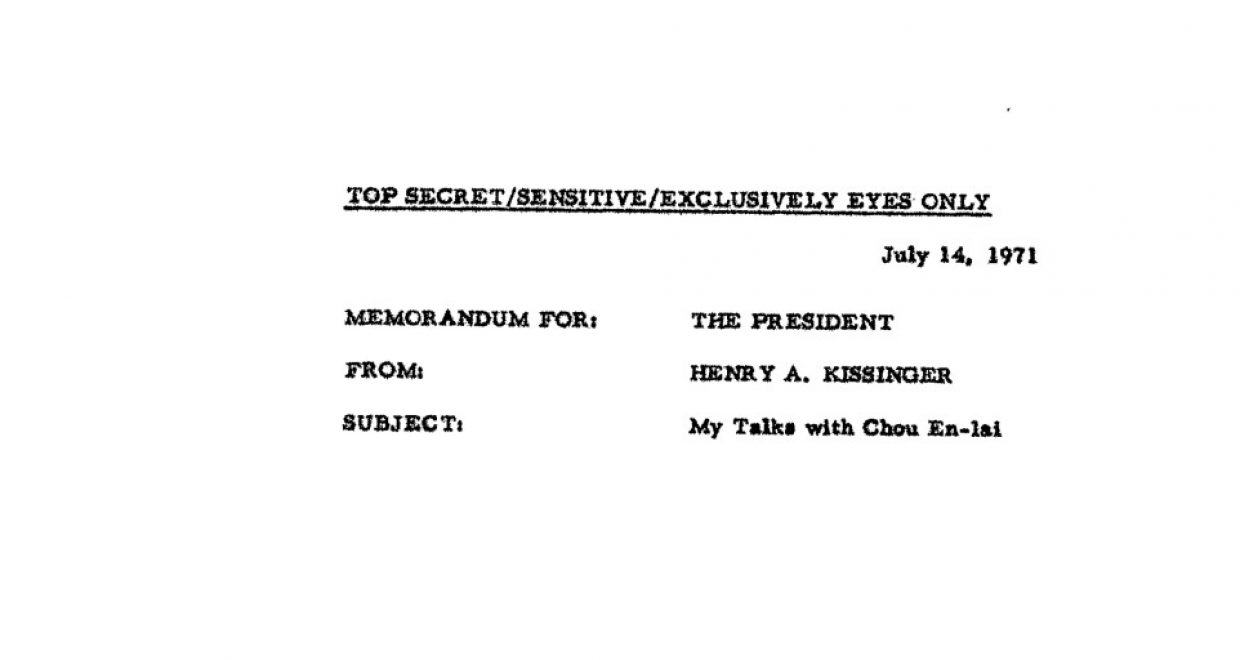

There are so many possibilities! Given my current research, I’d be most interested in seeing the first meeting between Henry Kissinger and Zhou Enlai in 1971. Kissinger had forgotten his own shirts and had to borrow ones that were too big; he worried that he looked like a penguin. He had in front of him a thick briefing book. Observers described him as twitchy. Zhou Enlai, in contrast, was elegant and self-possessed and had before him only a small piece of paper with a few jotted notes. I think the psychological dynamics of this meeting had far-reaching consequences, creating for Kissinger a fascination with – and a kind of inferiority complex toward – Zhou and China. I’d like to see and hear what was said and how it was said, to read the facial expressions and body language, to sense the atmosphere. Even when we have transcripts (as we do for this meeting), we miss out on so many of the important intangibles.

Modern American History’s first print issue will appear in 2018. Sign up for online content alerts and follow us on Twitter @ModAmHist. Article submissions and 250-word proposals for special features can be sent to mahist@bu.edu.

Main Image Credit: Henry Kissinger, top secret memo to the President regarding his visit to Beijing, July 14, 1971, National Archives, College Park