Why (not) Feathers? Period Hands and Material Encounters in Colonial Peru

This blog accompanies Stefan Hanß’s Historical Journal article ‘Material Encounters: Knotting Cultures in Early Modern Peru and Spain’.

Those of us who have seen Peruvian feather-work on display in museums will remember the striking visual experience of these objects. Their vibrant colours and shiny surfaces enthrall museum visitors still today, yet hardly any of us would describe Peruvian feather-work as sixteenth-century Europeans did. Seeing such artefacts for the very first time, Europeans were “at a loss to describe the aigrettes, the plumes, and the feather fans.” Spaniards said Peruvian feather-work “looked like very fine gold” and compared feathered items with silk, silver cloth, and high-quality velvets.

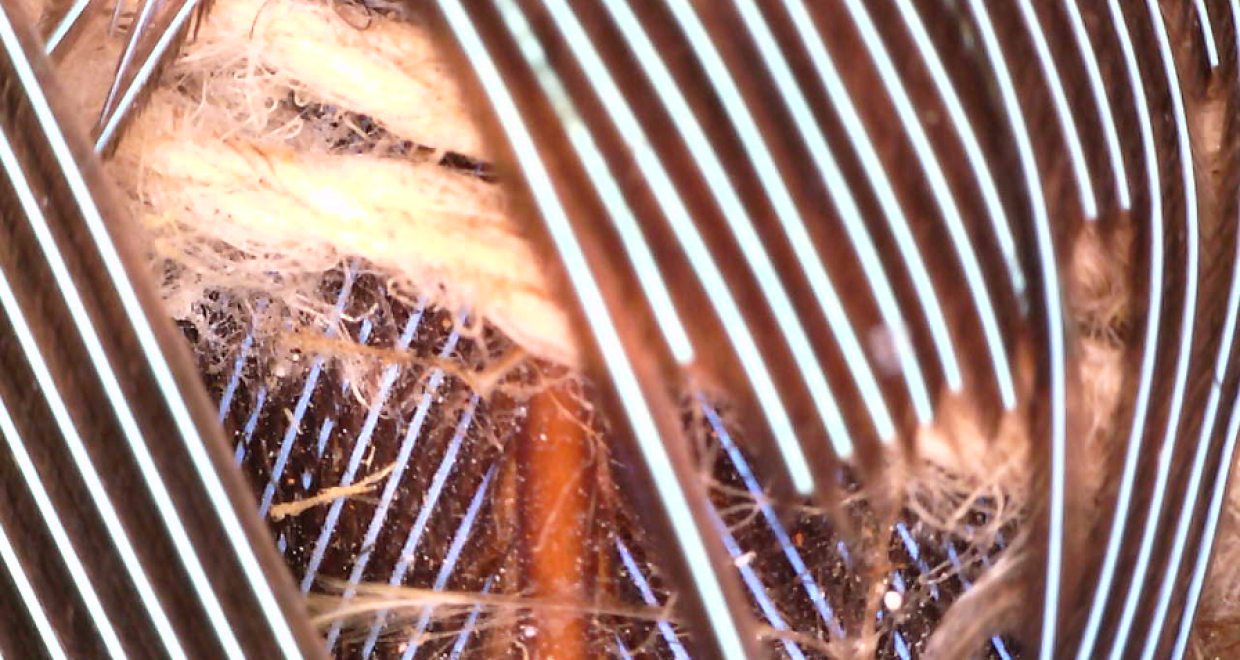

In my article, I try to make sense of such contemporary descriptions by contrasting archival evidence with actual surviving objects. Using the digital microscope as a new tool of the historian of material culture, I explore what it meant to manufacture, see, handle, touch, and marvel at feather-work. By doing so, a thus far unknown story unfolds: a story about the role of objects in encounters between indigenous Peruvians and Spaniards.

We tend to think of Peruvian feather-work as ‘typical indigenous artefacts’, prototypes of ‘pre-Columbian objects’. It is true that indigenous Andean cultures manufactured feathers into a variety of products. In Inca society, the metallic iridescence of brilliant feathers became emblematic of royal artefacts. In a society whose rulers fashioned themselves as sons of the sun and in which birds were associated with the divine and spiritual, indigenous artisans harnessed materials and skills to emphasize the iridescence of feathers.

However, there is a story to tell that reaches beyond the moment of conquest. Highly specialized artisans continued to manufacture feathers after the arrival of the Spaniards and made feather-work relevant for a colonial society. My article explores the role of feathers in colonial households, spiritual communities, and feather-workshops. Furthermore, my article allows readers to understand feather-working as a type of intricate knowledge involving complex processes of knotting and weaving. Digital microscopes help us better appreciate the artisans’ stunning cognitive achievements.

In the sixteenth-century, both indigenous Andean and European societies held such artisanal knowledge in high esteem. Manual dexterity, I argue, was a skill which linked indigenous and European societies through the expression of knowledge and communication of cultural concepts regarding the transformation of materials. Feathers and luxury textiles, both composed of intricate knotting techniques and characterised by striking textures and qualities, allowed people to associate the feather-worker’s products with subtlety and ingenuity. I posit the concept of ‘period hands’ to highlight manual dexterity, tangible production, and the haptic perception of feather-work. Accordingly, I explore a shared material world that connected Spaniards and Peruvians.

I decided to study objects with new technologies in order to develop new narratives about the past. My article on feather-work in colonial Peru shows, above all, that we should no longer differentiate between non-literate (material) Native Americans with feathers on their heads and literate Europeans with feathers in their hands. Far more important should be the historian’s distinction between non-literacy and knot literacy as this separates or connects cultures in the stories that we tell about the past.

Image credits: A Peruvian feather-work textile from c. 1530–1660 examined under the microscope. Detail of The British Museum, Am2006,Q.12, 81 x 54 cm. Photograph taken with a Dino-Lite USB microscope AM7013MZT. © Stefan Hanß.

Warm thanks to Dr John Lee (Manchester) for commenting on a first draft of this blog entry.