Working Together to Find and Protect Unmarked Graves

Janvier, Alberta | 2019

It was a cold October morning in northeastern Alberta.

I had been invited by the Chipewyan Prairie First Nation (CPFN) to conduct a small ground-penetrating radar (GPR) survey of a historic burial ground on one of their reserves. Warmed by eating my fill of moose fat and dry meat, we jumped out of a community member’s large pickup truck. We had arrived at a small sandy clearing amidst tall jack pines, overlooking a nice clear lake (Figure 1). The remains of one lone wooden cross stood near the center of the clearing, signaling we had arrived at the Cowpar Lake Burial Ground.

CPFN is an Athabaskan speaking, Déné’suline (or “Chipewyan,” a term derived from Cree) community and signatory of the historic Treaty no. 8. Since contact, the families of CPFN (along with most Indigenous nations) have suffered population declines, principally as a result of hardships (i.e., diseases) brought on by increasing contact with European settlers and their descendants. Over the course of a particularly hard winter around 1918, Spanish Flu ripped through CPFN territory and affected the families living at Cowpar Lake. Fourteen Déné’suline succumbed to what was believed to be the flu and were buried in the present burial ground the following spring. These graves would have likely been marked originally (and some wooden crosses were placed here in the later 20th century), but since then the burials of CPFN’s relatives have become largely unmarked.

After a quiet prayer, we set about our work. Elders told stories about what was known about the people buried at the site. Community members cleared the area for the GPR survey, the GPR was assembled, and data collection began. Soon, the small area had been surveyed and the graves were easily identified. As a team, we had determined the boundaries of the burial ground allowing CPFN to erect a protective fence in confidence that they would not disturb their relatives’ graves. Optimistic with the results, the community members became extremely excited about the potential of GPR and archaeology to address their needs and interests. Suddenly, while standing in this remote clearing, a flurry of new sites began to be proposed. One community member even offered to take us in his jetboat to additional burial grounds in the hopes that these too could be non-invasively recorded. Unfortunately at that time we had to go back to our homes in Edmonton, but we would be back in 2021 (following everyone becoming fully vaccinated) to take them up on those offers and to start surveying additional sites of community interest. As a result of this optimism, excitement, and burgeoning relationships, my own doctoral dissertation research is continually being formed around and by these connections.

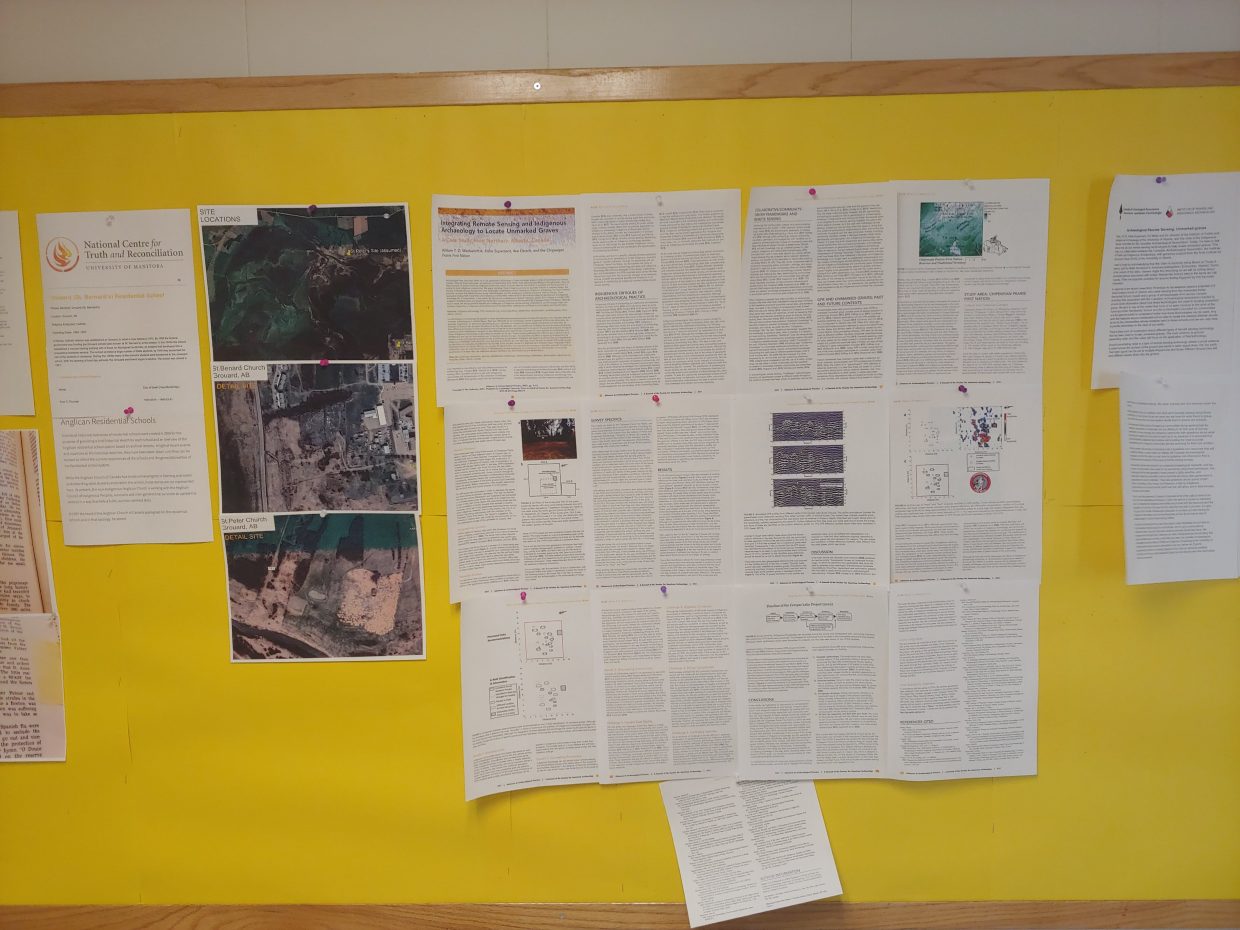

We recently published the results of this survey in Advances in Archaeological Practice as a small but interesting case study; however, we did not anticipate the rapid impact that this piece would have on other Indigenous communities. Thanks to the generous support from the journal, this article was released under free access following the tragic discovery of unmarked graves at the former Indian Residential School in Kamloops, BC. As a result of the Kamloops discovery, there have been a flurry of calls by Indigenous communities from across Canada to locate their missing children using non-invasive archaeological remote sensing techniques (specifically, ground-penetrating radar). From the beginning it was clear that this endeavour would be led by these communities and that there was a great need for active collaborations between them and archaeologists. We first found out that our article was being read by other First Nation communities when we were given a packet of ‘required readings’ by a community which included our new article. Later, while visiting said community, we attended a gathering for residential school survivors. When we arrived on reserve, we found the pages of our article posted on the walls of the community center (Figure 2)!

While the present crisis has acutely emphasized the importance of non-invasive archaeological techniques, archaeologists must continue to be respectful of Indigenous communities’ needs and objectives. Our project demonstrated that only together with our combined skills and knowledges can we make meaningful contributions to the search for missing loved ones.

We must follow their lead.

Pictures:

This post accompanies William T. D. Wadsworth’s Advances in Archaeological Practice article Integrating Remote Sensing and Indigenous Archaeology to Locate Unmarked Graves: A Case Study from Northern Alberta, Canada.