The Poor you will always have with you

The RCPsych Article of the Month for October is from BJPsych Bulletin and is entitled ‘Placing poverty-inequality at the centre of psychiatry’ by Peter Byrne and Adrian James

The eight words of this title have been (mis)quoted for 2,000 years – mostly to justify levels of family poverty that no democracy should accept. The words might also be addressed to clinic-based psychiatrists / ward-based colleagues about “hard to engage” / harder-to-discharge patients. Or to those of us working in inner city Emergency Departments. Our Editorial reflects on how Poverty drives so much of our work as psychiatrists, and the worst possible outcomes, for example deteriorating physical health and premature deaths. Both are preventable. Anything we do to reduce or mitigate poverty-inequality will reduce rising premature mortality – not least among the group worst hit, people with severe mental illness. Anti-poverty actions will also reduce the duration and severity of mental disorders, and there is increasing evidence they could prevent many mental disorders.

Inspired by Michael Marmot and other public health colleagues, our article was conceived before Covid-19 and nurtured by BJPsych Bulletin Editor Norman Poole who facilitated a themed October 2020 issue. The virus may have “come from nowhere” and surprised our leaders, but ten years of UK austerity had already pushed one million children into poverty, reduced the vital state services that protect our worst off citizens, and cut back public health budgets by average 40%.

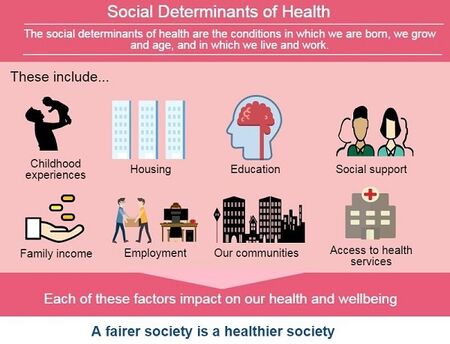

Inequality is a difficult concept. It’s not binary – the richest “1%” versus the poorest. Marmot’s health gradient is relevant to the extremes and to those of “us” in the middle. Inequalities predict illness, and poverty’s grim outcomes appear mediated by poor mental health. Most inequalities are economic but there are parallel and additive inequalities experienced by black and minority ethnic communities. Again, Covid-19 reveals and exacerbates inequalities.

Evidence points to solutions. From this issue, this means listening to service users about what matters to them, Housing First, beating tobacco poverty, a just and fair benefits system, and using our knowledge from cellular to epidemiological. I thank all contributors and the Journal for making these articles open access. Have a look at what happens to Gary Cooper’s character when he attempts some wealth redistribution: In the movie, psychiatrists are called in to discredit Mr Deeds – to stop him standing up for the “little guy”.

Recently, Warren Buffet gave away his fortune and was not stopped by psychiatrists. It’s just as bad to do nothing: you need to do more than read these papers. I expect you to break your silence on Poverty. Call it out, collaborate with your patients on mitigation for them and others, and work locally to lessen the impact of inequalities. And yes, this will be seen as “political”. Even something as essential as Covid vaccines are also political: who announces it? Who gets it first? Will it be accessible across our communities? Across the world? Our expertise begins with health and social care: recent UK “reforms” have not delivered, and we need to be heard as systems change again. We must have a say in what our post-Covid, or living-with-Covid, societies look like. To recoin a phrase, we will always be with the Poor.

Why I chose this article:

Byrne and James’ editorial for this special edition of the BJPsych Bulletin on poverty and inequality is a powerful rallying call for government and mental health services to do better. The edition as a whole stresses how adversity and disadvantage drive mental disorders and physical illness, limiting life chances and expectancy, but this editorial goes further. Mental disorder is identified as themediator between inequality and disease, so if you are poor, life really is “nasty, brutish and short.” Enter politics. Part of the solution requires psychiatrists to recognise themselves as specialists knowledgable of public health and able to engage locally to address inequalities that worsen outcomes. The Royal College of Psychiatrists is stepping up. Are you? Please read this editorial and the accompanying articles to learn more about practical steps we can all take to improve the health of our patients.

Norman Poole

Editor-in-Chief, BJPsych Bulletin

my observation is that psychiatrists get distracted by organisational concerns about risk management, patient flow, bureaucracy and discharge of patients back to primary care, which in effect derails us from focusing on what matters most to patients and the community. Very inspiring material indeed and a stimulus to rethink my clinical practice.