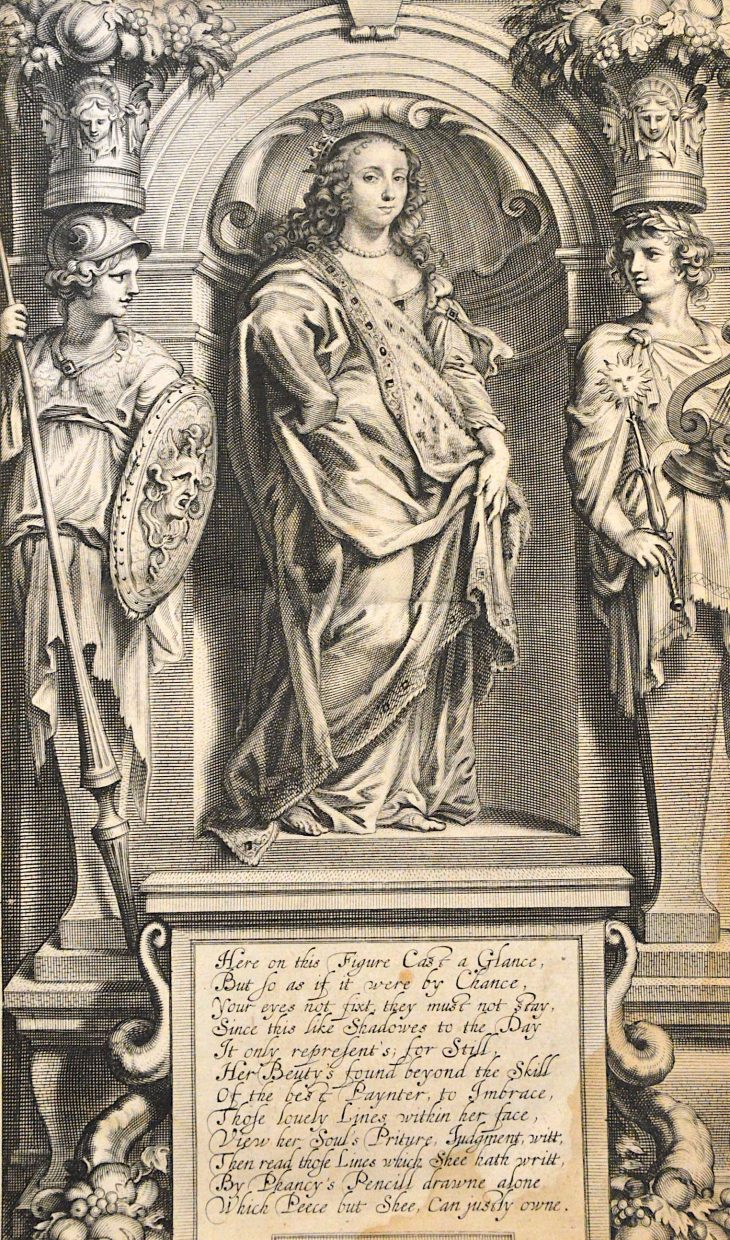

Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673) in the Undergraduate Classroom

This blog accompanies E Mariah Spencer’s History of Education Quarterly article ‘A Duchess “given to contemplation”: The Education of Margaret Cavendish‘

How might Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673) find a place in our classrooms? She illustrates not only how to navigate a world with restricted opportunities but also how to consider tragic situations in which no good option exists.

E Mariah Spencer wonderfully describes how Cavendish challenged the narrow categories of early modern culture. Never having been taught classical languages, she possessed “Poetical and Philosophical Genius.”[1] She enclosed herself “like an Anchoret” in Protestant England, drawn to contemplation.[2] Exiled amidst the English Civil War, she wrote of her “mallancholy humer,” which she claimed spurred creativity.[3] Reading Plutarch, she was drawn to “emulate Julius Caesar most,” despite her gender.[4]

Being an outsider in a world of men could lead to frustration about the limited roles for women. In her Sociable Letters, Cavendish suggests she could not spin wool but only “scratch Paper.” She asks, “Leave me to that employment.”[5] Spencer insightfully notes that Cavendish’s anger also led to educational theories that emphasized, especially after her return to England at the Restoration, intensive reading, gender equality and delight in place of pedagogical harshness. She imagined a fictional world in which an Empress established a learning society, created a religious system, and, like Caesar, could lead an army.

But this was fiction. In our world, as Spencer brilliantly recounts, Cavendish turned to several ways for women to be educated. A fascinating theorist of humanist educational experiments, she asserted that women, as well as men, possessed rational souls. She herself read widely. She considered private tutoring for women. Then, in one story, she imagined a Female Academy. But, Spencer recognizes, many of Cavendish’s fictional worlds ended with women embracing either death or marriage. The recipients of private tutoring, like the “She-Anchoret” in Cavendish’s longest story, were liable to unexpected death. The Female Academy might attract the hostility of males, not least as it suspiciously resembled a cloister. When Cavendish wrote about an actual cloister, if one with a secular curriculum, by the play’s end the cloister was dismantled, the heroine safely married. She repeatedly envisioned limited and tragic endings, even for independent-minded women.

This is not cognitive dissonance. Cavendish’s works can show how to live amidst inevitable restrictions, even when those restrictions go so far as to seemingly leave no option at all. One specific example that is easily accessible to undergraduates is Cavendish’s story “The She-Anchoret.”

“The She-Anchoret” features an orphan, whose father’s dying wish is that she “live chast and holy, serve the Gods above” amidst the masculine world’s dangers.[6] She becomes a renowned anchoress, if more natural philosopher than Catholic nun, and engages in a series of discourses to a wide swath of people in her country. As Spencer notes, she precedes John Locke in suggesting that children be instructed with reason, not be “forced to learn by Terrifying.”[7] Generally, the She-Anchoret speaks of a God of concord who rewards “vertue,” set against a Nature prone to discord.

However, the She-Anchoret’s fame attracts the curiosity (and lust) of a neighboring (and married) monarch, who threatens to declare war against her country if she does not succumb to his advances. She cannot violate her vows, her father’s wishes, her chastity, and her country; thus she poisons herself before the wicked king’s ambassadors. Her death may express despair about the opportunities for women in public, especially as suicide was proscribed by Christianity.[8] But Cavendish focuses on the She-Anchoret’s voluntary resistance. After her death, the She-Anchoret is honored by altars, pyramids, a statue and tower. She remains an example that “all the world might know and follow” in concord centered on her virtue unto death.[9]

The character’s choice to commit suicide rather than violate her vows resembles a contemporary account of a boy ordered by paramilitaries in Northern Ireland to commit murder or face execution; instead, he hanged himself. Theologian Rowan Williams interprets his death as a “passionate refusal of the terms in which the options had been presented,” a painful turning away from a world of discord. Thus, however regrettable, the boy’s sad death may still be seen as a “converted act” in a world of restrictions.[10] Likewise, Cavendish’s character makes a moral choice in rejecting the fate presented her.

Discussing “The She-Anchoret” together with Spencer’s article may inspire students to look with renewed sympathy at all those who must act in a world that provides them no good options. E Mariah Spencer’s article provides a wonderful introduction to Margaret Cavendish and all the stages of her life and thought. Cavendish shows us what it means to be educated in the world as it is, even as she also theorizes about the world as it could be if women had more opportunities.

[1] E Mariah Spencer, “A Duchess ‘given to contemplation’: The Education of Margaret Cavendish.” History of Education Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2021), 213-39, at 214.

[2] Spencer, “A Duchess ‘given to contemplation,’” 219.

[3] Spencer, “A Duchess ‘given to contemplation,’” 222.

[4] Spencer, “A Duchess ‘given to contemplation,’” 227.

[5] Spencer, “A Duchess ‘given to contemplation,’” 229.

[6] Margaret Cavendish, “The She-Anchoret,” Natures Picture Drawn by Fancies Pencil to The Life (London: A. Maxwell, 1671), 545.

[7] Spencer, “A Duchess ‘given to contemplation,’” 230.

[8] Jacqueline Pearson. “’Women may discourse… as well as men’: Speaking and silent women in the plays of Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 4, no. 1 (1985), 33-45.

[9] Cavendish, 357.

[10] Rowan Williams. Resurrection: interpreting the Eastern gospel. Pilgrim Press, 2002. 41-2.