Dispersion of adeleid oocysts by vertebrates in Gran Canaria, Spain

The latest Paper of the Month for Parasitology is “Dispersion of adeleid oocysts by vertebrates in Gran Canaria, Spain: report and literature review” and is freely available.

When we think of parasites often our first thoughts are of six or eight-legged creatures crawling on our skin, or white spaghetti-like worms coming from our beloved pet’s rear end. However, there is a whole world beyond the eye, which comprises very small, generally single-cell organisms, known as protozoans.

Parasites are generally adapted to their hosts so the route of transmission to other hosts involves direct contact with faeces or other body fluids, being injected by vectors, or carried in prey species like Trojan horses. However, the case presented here is unique.

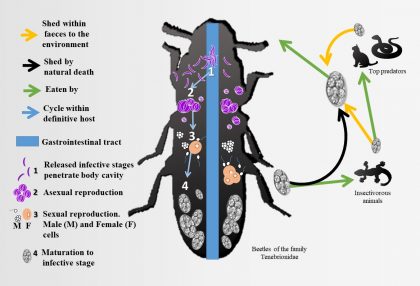

Invertebrates, like people and their pets, also have parasites (external or internal, big, or small). One such parasite is the protozoan Adelina, whose life cycle occurs inside the insect’s body cavity (fig.1). Since there is no way out through natural openings, the insect host needs to be consumed by a predator, usually an insectivorous animal. Once eaten, the infective stages survive the gastrointestinal acids and enzymes, are shed in the faeces of the predator, and which in turn can be eaten by the invertebrate, thus continuing the cycle again.

This peculiar biological feature enables the use of animal faeces to search for these parasites without killing any insects, some of which may be endangered endemic species.

On Gran Canaria, one of the Canary Islands, there are no reports of these species, or indeed no recent reports in Spain, so the aim of this work was to report and review this parasite species using faecal samples from 476 predator species: 298 feral cats, 117 California kingsnakes (Lampropeltis californiae), 10 Algerian hedgehogs (Atelerix algirus caniculus), 15 feral dogs and 36 birds of seven species.

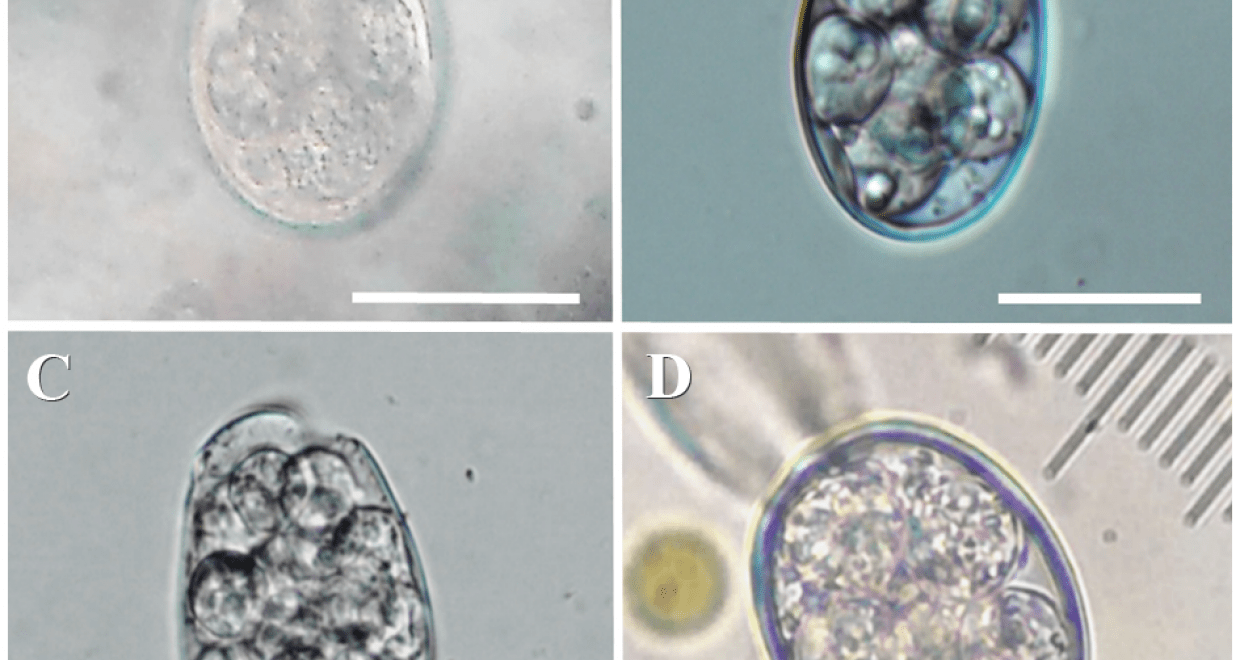

Adelina parasites were found in stool samples from four animals: Adelina tribolii in three kingsnakes (fig. 2B, C and D), and Adelina picei in one feral cat (fig. 2A).

California kingsnakes, unlike cats, do not eat invertebrates therefore the finding of adeleids in their faeces could be explained through consumption of small mammals and endemic lizards. These prey species feed on insects, thus, Adelina spp. may have originated from invertebrates within their gastrointestinal tract, which would increase the number of infective stages inside the snakes or other top chain predators.

Since Adelina spp. may cause death of larval stages in beetles, the feeding habits of the predator (on the ground, trees, on the wing…) would determine the success of spotting the parasite. The definitive hosts for these Adelina species could be beetles of the family Tenebrionidae, in which A. picei and A. tribolii has been previouslydescribed.

These constitute the first baseline data for invertebrate pathology studies in the Canary Islands. The further understanding of the role of this protozoan in invertebrate population dynamics is important on an island where most of the fauna is endemic and/or endangered. Thus, the Canaries, and other similar islands, could be utilized as model ecosystems.

With the appropriate genetic sampling, predators could be useful as sentinels for invertebrate diseases worldwide.

The paper “Dispersion of adeleid oocysts by vertebrates in Gran Canaria, Spain: report and literature review” by Kevin M. Santana-Hernández, Simon L. Priestnall, David Modrý and Eligia Rodríguez-Ponce, published in Parasitology, is freely available.