Stealth Intelligence

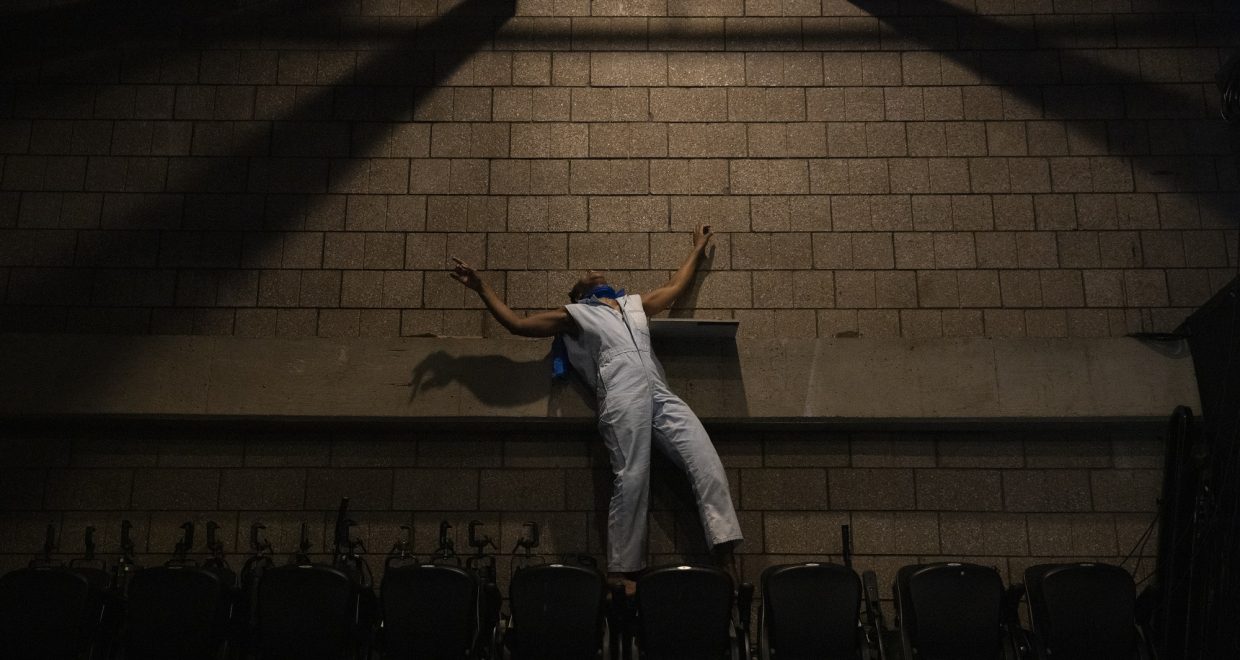

We live in an era of absence. Lockdowns, quarantines, hospitals, and face masks: fear of contamination disappears the body from public space and discourse. Antibacterial soaps and hand sanitizers are ubiquitous; they reinforce a fear of touching and inhibit our sensory awareness.

Pandemics create new rules and protocols that allow nation states to erase agency. So, what can be salvaged in circumstances such as these? What can be decomposed? In what ways can absence be celebrated and not forced down our collective throats only to silence us into acquiescence?

As I reflect on my Provocation, “The Artist Is Not Present,” I remember the story of Anyanwu in Octavia Butler’s science fiction novel, Wild Seed. Anyanwu, one of the main characters, is immortal and has the power to shapeshift. For a time, Anyanwu disappears from the human realm, transforms into a dolphin, and escapes the powerfully destructive energy of her antagonist, Doro, who is also immortal and the only being on earth who can kill her. When Anyanwu turns into a dolphin, Doro cannot trace her. Anyanwu becomes invisible to him. He can only find her when she is on land.

Doro is like a parasitic nation-state, corporation, or patriarch that thrives off the labor of others and disposes their bodies when he no longer needs them. The story of Anyanwu, however, positions absence under water, in the abyss and in the shape of the dolphin. Doro seems to be the most powerful being on Earth but Anyanwu’s power is more creative and more stealthy. While Anyanwu shapeshifts into the depths of the ocean, Doro wears the skin of other humans on land. It fascinates me that Anyanwu incidentally discovers that her greatest strength resides in her surreptitiousness as a deep-sea cetacean, and her capacity to escape Doro’s reach: “She was a dolphin. If Doro had not found her an adequate mate, he would find her an adequate adversary. He would not enslave her again. And she would never be his prey” (1980:211).

Thanks to Butler and other Black feminist writers, I find strength in the evolving story of cetaceans and their unique ability to move surreptitiously undersea without temporal boundaries. In Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s Undrowned (2020), a brilliant treatise on marine mammals and Black feminism, she recalls how the gray whale, nearly extinct in the 1950s, surprised scientists by reappearing in 2013. Gumbs marvelously links gray whales to the bones of her enslaved African ancestors who perished in the Middle Passage: the whales have a propensity to feed on deep sea sediments that may have contained her ancestors’ bones. She imagines new possibilities that arise from prolonged absence and disappearance: “So there is actually a digestive truth to the idea that the ancestors we lost in the transatlantic slave trade became whales” (2020:118).

The sediment of ancestors’ bones gives way to the whale fall, the process of a whale’s decomposition after it dies and falls to the ocean floor, and the whale fall provides nutrients for deep water creatures. Absence gives way to decomposition. Decomposition regenerates, renews, and eventually destroys structures like prisons, detention centers, and police stations that keep us separate, subjugated, and silent. Everything decomposes eventually…like the whale fall.

This blog relates to the newly published provocation ‘The Artist Is Not Present’, free to read in TDR until 31 May 2022.

References

Butler, Octavia. 1980. Wild Seed. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Gumbs, Alexis Pauline. 2020. Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals. Chico, CA: AK Press.mayfield brooks’s Provocation, “The Artist Is Not Present,” is published in 66:1 (T253).