How sociality affects parasitism

We are delighted to announce Parasitology’s joint-prize winners for the 2022 Early Career Researcher Award (for papers published in the journal in 2021). Only researchers who are no more than 7 years post award of their PhD were eligible to receive the award. Decisions on the winning papers were made by Russell Stothard and his team of supporting Editors.

The winning papers really reflect academic excellence within laboratory culture and experimental observation studies. We hope each article will be one of many within their future efforts in parasitological research. We wish them all the very best in the next steps of their careers.

The evolutionary arms race between parasites and their hosts have been fascinating/puzzling scientists for many years, and current World events have made even clearer about the importance of understanding host-parasite interactions.

It is intuitive to think that in a group of organisms, whether fish, birds or humans, the increased proximity and contact between individuals increases the risk of parasite transmission, which may lead to increased risk of spreading a disease. Scientists have been finding this positive relationship between contact-transmited parasites and group size or density in many taxa for monospecific groups. But what happens when the group is composed of different species, which may vary in their susceptibility to a certain parasite?

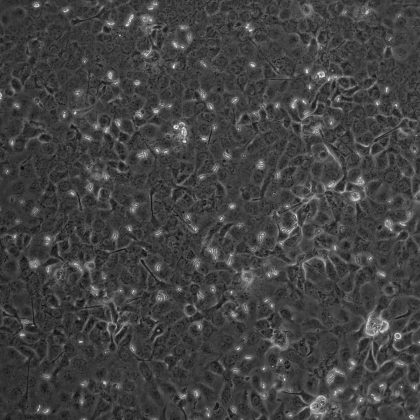

To answer this question, a group of Scientists, led by João Gameiro from the Centre of Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes in Lisbon (Portugal) and by Jesús Veiga from the Experimental Station of Arid Zones in Almería (Spain), have studied mixed-bird colonies recently established on artificial breeding structures in the Special Protection Area of Castro Verde, Southeast Portugal (Fig.1). These artificial structures, originally aimed at recovering the populations of a small colonial falcon, the Lesser Kestrel (Falco naumanni), attracted other species of birds, creating mixed bird colonies, that provided an excellent opportunity to study the influence of multiple hosts species on host-parasite interactions.

Sampling more than 250 nests across 30 different colonies, the team focused on the four most common hosts: Lesser Kestrels, European Rollers (Coracias garrulus), Spotless Starlings (Sturnus unicolor) and Feral Pigeons (Columba livia). They studied how the abundance and composition of ectoparasites, among flies, mites, and lice, varied as a function of colony size, proximity of nests, the host species and the number of nests of each host.

The study, published in Parasitology, shows that, contrary to what happens in single-species groups, the size or density of the colony did not influence the composition or abundance of parasites in these mixed-species colonies.

“In fact, it is the identity of the hosts – if it is a roller or a pigeon, for example –that influences the composition of ectoparasites in these colonies the most. Because of that, the number of nests of each bird species is the key determinant influencing the abundance of Carnus hemapterus: a small blood-sucking fly that infests many species of birds, and the main parasite found in these colonies”, explains João Gameiro. “Regardless of its size or density, a colony will have more parasites if it is dominated by lesser kestrels, and less parasites if the colony is dominated by starlings”, he adds.

“What explains these results is the susceptibility of each bird species to each parasite. Less susceptible host species to C. hemapterus, like starlings, will not attract as many parasites reducing the parasite charge supported by each nest in the colony”, adds Jesús Veiga.

This study shows that the increasing contact between birds of different species in these colonies makes the interactions between ectoparasites and their hosts more complex, challenging what is currently known about the relationship between parasitism and sociality.

João Gameiro and Jesús Veiga have been awarded the Early Career Researcher Prize for submitting the paper entitled: Influence of colony traits on ectoparasite infestation in birds breeding in mixed-species colonies and is freely available to download.