Lost in Time

The latest Paper of the Month for Parasitology is “A remarkable assemblage of ticks from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber” and is available open access.

The world is in constant change and we only glimpse what existed in the past. Existing families, genera and species tells which lineages survived the ravages of time. Sometimes large genetic distances between sister-lineages hint at large gaps previously filled by other extinct families, genera, or species. Beyond being one interpretation for large genetic distances in phylogenetic trees, sequence data and existing species cannot readily tell us what biodiversity existed before. Fossils can, however, give a glimpse of families, genera, or species that existed before.

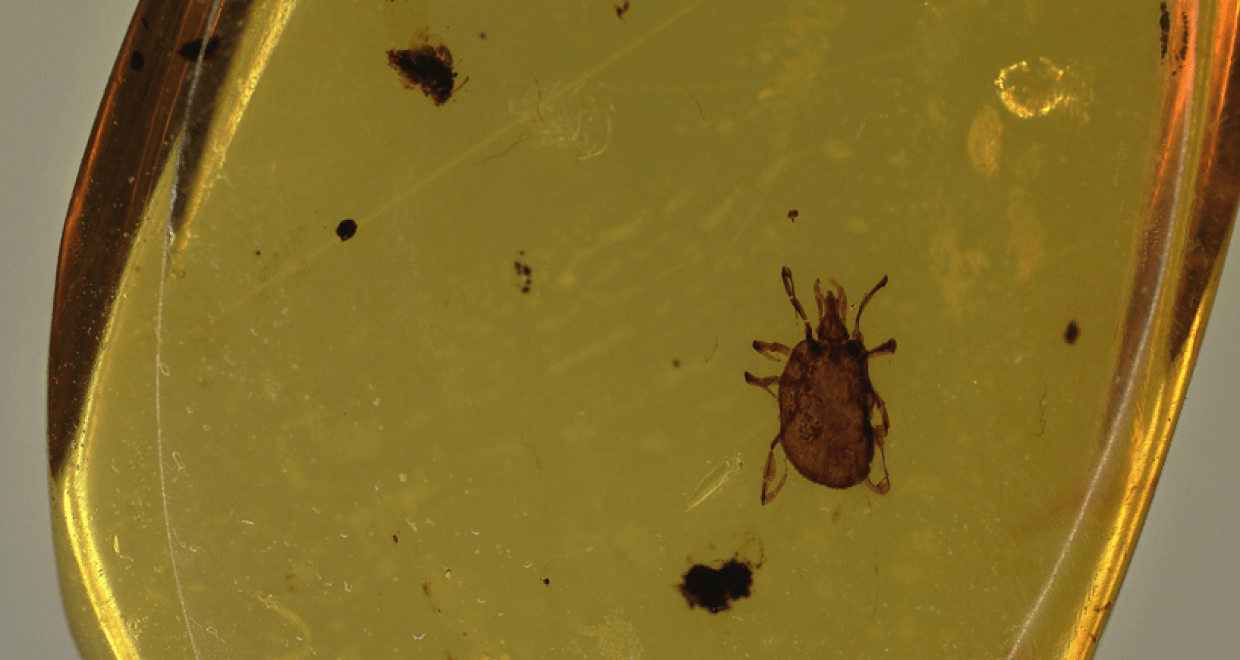

Amber is a rich source of invertebrate fossils that constantly turn up new families, genera, and species. To become an amber fossil, an organism needs to be trapped in tree resin oozing from injured trees, which hardens and gets buried beneath sediment before fossilization at high pressure and temperature. Amber fossils are relatively common, although tick fossils are not abundant. However, quite a large number of unique tick species have been discovered in amber. The oldest ambers that hold ticks are Burmese amber, dated ~100 million years ago, making this also the minimum age of origin for many families and genera found in amber.

Until quite recently, ticks were composed of only three families, the hard ticks (Ixodidae), soft ticks (Argasidae), and the enigmatic Nuttalliellidae composed of a single species. A completely new tick family (Deinocrotonidae – terrible ticks) closely related to the Nuttalliellidae was described in 2017. The families can be readily distinguished based on unique characteristics such as a soft body for soft ticks with mouthparts beneath the body, the presence of a shield (scutum), and sclerotized body for hard ticks with mouthparts terminal, while the Nuttalliellidae and Deinocrotonidae have a pseudo shield and a soft body that resemble soft ticks, but with sub-terminal mouthparts.

The possibility that another tick family may have existed seemed remote until a Burmese amber fossil was found that confounded classification of the recognized families. This tick has a soft body like soft ticks but well-developed terminal mouthparts. It really seems as if someone took the mouthparts of a hard tick and glued them to the body of a soft tick, hence its name, the Khimairidae, referring to the Greek chimera: a mythological beast composed of different animal parts. This finding suggests that tick biodiversity was much greater than estimated to date with the potential that many lineages, families, genera, and species went extinct over the course of evolution. To underscore this, the study also described the oldest hard tick specimen for the Prostriate lineage (genus Ixodes) and a new species of Deinocrotonidae. This brings the number of unique extinct tick species found in amber to 14. It also brings the number of existing hard tick genera found in Burmese amber to three, including Ixodes, Amblyomma, and Haemaphysalis, which put the minimum age for all of these genera to at least 100 million years. It is expected that the study of Burmese amber will continue to lead to new and exciting discoveries in the tick world.

The paper “A remarkable assemblage of ticks from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber” by Ben J. Mans, Lidia Chitimia-Dobler, Stephan Handschuh, and Jason A. Dunlop, published in Parasitology, is available open access.