How ITV launched modern research on primate facial expressions

‘Dutchman mugs at monkeys’: the headline broke news of pioneering research at London Zoo. The Netherlander was Jan van Hooff of Utrecht University, and he worked on the evolution of facial expressions. Regent’s Park made an auspicious venue for this budding student of animal behaviour: an early experiment in TV science communication was under way. The zoo was home to a film unit funded by Granada TV, one of several regional companies comprising ITV, the commercial service introduced in 1955 to break the BBC monopoly on broadcasting in the UK. Although ITV fundamentally transformed British television, a combination of archival red tape and academic disdain for the BBC’s ‘low-brow’ competitor has left its history largely untouched. Returning to those heady years of TV competition, my article challenges the common assumption that the BBC Natural History Unit always led the pack.

Arriving as a student to work with the zoo’s unrivalled primate collections overseen by curator of mammals Desmond Morris (soon famous for The Naked Ape), Van Hooff quickly found himself courted by Granada to advise on a programme about his research. Granada was hungry for ‘serious’ TV with broad-based appeal to appease critics who accused ITV of peddling cheap entertainment shows. Van Hooff’s work promised to combine informative science with entertaining imagery of monkey faces. For the fledgling scientist, conversely, collaboration with Granada provided high-quality footage which he had neither the funds nor the expertise to produce on his own.

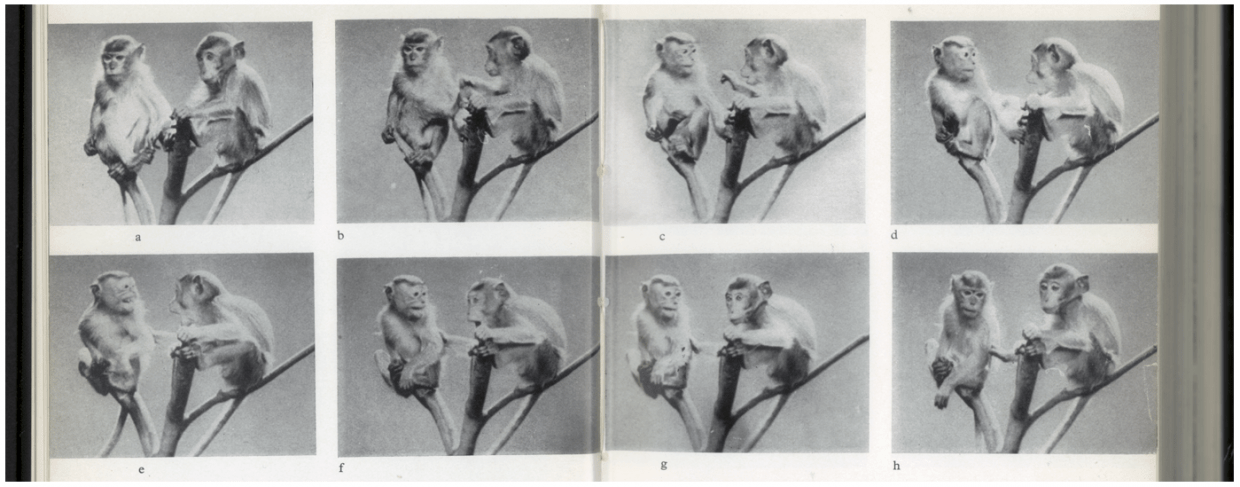

With support from the British Society for the History of Science, I purchased a digital copy from the ITV Archive and watched black-and-white footage of macaque ‘threat faces’ and playful chimps. The images framed simian faces in much the same way as human actors, newsreaders, and interviewees were routinely presented on TV. Wittingly or unwittingly, Granada applied techniques of shot composition—talking heads, close-ups, ‘two-shots’ of communication partners—to monkeys and apes. This televisual language aided Van Hooff’s analysis by isolating his object of study and produced arresting images for Granada.

Granada patronage gave Van Hooff an early edge over his rivals in a new ethological specialism. It allowed the young scientist to experiment with new film-based research practices, including frame-by-frame analysis, which encouraged others to follow suit. Researchers continue to cite Van Hooff’s debut research project as a textbook classification of primate facial expressions. There must be many more examples of the productive interplay of commercial media and animal behaviour science.

Commercial television and primate ethology: facial expressions between Granada and London Zoo