Rat lungworm’s crafty exploitation of active transmission routes

The latest Paper of the Month for Parasitology is “Rat lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) active larval emergence from deceased bubble pond snails (Bullastra lessoni) into water” and is freely available.

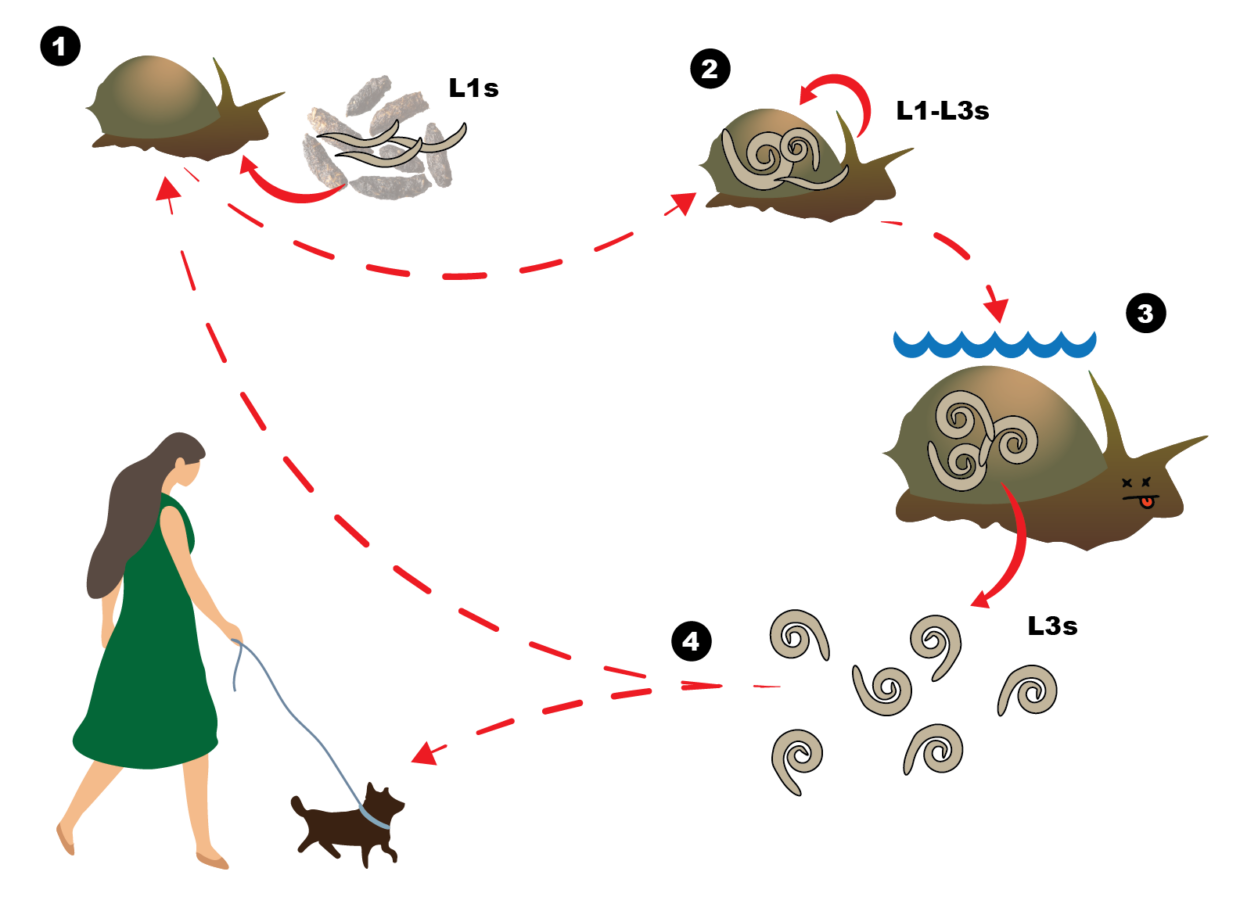

Parasites have a knack for surprising us with their ingenious ways of exploiting transmission routes to maximise their potential for infecting a new host. Angiostrongylus cantonensis, commonly known as the rat lungworm, is no exception. This worm has a complex and intriguing life cycle; the adult worms parasitise the lungs of many species of rat where they reproduce, and first stage larvae (called L1s) are shed in large quantities in the rat’s faeces. An unsuspecting mollusc (usually a terrestrial or freshwater slug or snail) may pass over the faeces and become infected with these L1s. These larvae then undergo a transformation inside the mollusc over the next 2-3 weeks, where they become infective third stage larvae (L3s). When a rat, or an “accidental” host such as humans and dogs, consumes a mollusc containing the L3s, they migrate their way into the hosts central nervous system. Although this migration doesn’t affect rats, it causes a huge immune response in the meninges of accidental hosts – which can be deadly for us and our canine companions.

The transmission route of rat lungworm to accidental hosts has been a subject of ongoing debate. While ingestion of infected molluscs has long been the established “passive” pathway, anecdotal reports and emerging evidence suggest that the “active” emergence of larvae from dead or drowned molluscs into water sources may play a more significant role than previously believed. We wanted to determine how long the L3s take to develop until they are capable of actively escaping a crushed snail submerged in water. To do this, we experimentally infected bubble pond snails (Bullastra lessoni) and removed a subset at different timepoints to count how many larvae emerge after 24hrs in water vs how many remained in the snail tissue.

Surprisingly, the larvae 2 months post-infection were the only ones that readily escaped the snail, meaning that the L3s must undergo some further maturity (not able to be seen morphologically) before being able to migrate into the water actively. This apparent month-long delay could also help explain the seasonal peak of rat lungworm cases in dogs; meaning that in addition to gnawing on a slug, drinking water contaminated with escaped infective larvae could be a source for dogs. We also observed that the total larval burden of the snails increased over the 3 months, indicating that this pesky parasite may actively migrate out of living snails or be passively released by dead ones, in order to find new snail hosts for recycling in the population and dispersal.

So with that in mind – take care to watch out for dead slugs and snails in your water sources and your pet’s bowl too!

The paper Rat lungworm (Angiostrongylus cantonensis) active larval emergence from deceased bubble pond snails (Bullastra lessoni) into water by Phoebe Rivory, Rogan Lee and Jan Šlapeta, published in Parasitology, is freely available.