Widows behaving ‘badly’: manipulating vulnerability to strengthen the English Catholic Community

This accompanies Jennifer Binczewski’s British Catholic History article Power in vulnerability: widows and priest holes in the early modern English Catholic community. The article recently won the Harold J. Grimm Prize for the best article in Reformation Studies, awarded by the Sixteenth Century Society & Conference.

On 16 February 1587, Godfrey Foljambe wrote to the Earl of Shrewsbury declaring that he had arrested his own grandmother, Lady Constance Foljambe, for recusancy.[1] As a vocal Catholic in post-Reformation England, Lady Constance’s entanglement with the law did not end with this familial betrayal. In 1589, John Coke, the rector of Tupton, asked the Earl to prevent her release from custody due to her potential ‘evil effect’ on the many recusants he had converted in her absence.[2] Apparently, this frail widow was ‘suspected to do most hurt in those parts’, as a Catholic who led others back to the faith.[3]

These letters led me to explore how widowhood influenced women’s activities in the post-Reformation English Catholic community. Initially, I focused on the vulnerabilities associated with widowhood, particularly how Lady Constance’s lack of a male protector left her open to attack from within her own family. However, the local anxiety over her religious influence gnawed at me. What could have incited such worry about a frail seventy-year-old widow? This led me to look for other Catholic widows who held sway in their communities despite their supposed vulnerabilities.

My article, ‘Power in Vulnerability’, argues that early modern patriarchal structures provided specific opportunities for widows that were unavailable to other men and women, whether married or single. The financial and social independence experienced by some noblewomen and gentlewomen at widowhood enabled the adaption and creation of households to harbour priests. In addition, cultural stereotypes of piety and vulnerability surrounding widowhood produced a cultural camouflage for their illegal actions. Consider Eleanor Brooksby who, together with her sister Anne Vaux, famously hid seven priests at Baddesley Clinton during a four-hour search. Cultural deference to a widow’s house gave priests time to hide, resulting in an empty search for pursuivants. Other widows such as Dorothy Lawson and Lady Magdalen Montague likewise used their widowhood to harbour priests, host clandestine Mass, and catechize. Due to their legal autonomy, economic independence, and careful manipulation of gendered stereotypes, many Catholic widows had the means, opportunity, and relative invisibility to support the underground Catholic community. While widowhood, in history and historiography, is frequently considered a weak, liminal, or potentially threatening status for women, in a religious minority these weaknesses became catalysts for successful subversion of Protestant authority.

[1] A recusant was an individual who refused to attend Protestant services. For the letter, see Foljambe to the Earl of Shrewsbury, 16 February 1587/8, at Lambeth Palace Library, London, MS 3204, f. 121.

[2] John Coke to the Earl of Shrewsbury, September 1589, Lambeth Palace Library, London, MS 710, f. 19.

[3] Servant of the Earl of Shrewsbury to Francis Leake, 3 February 1587/8, Lambeth Palace Library, London, MS 3204, f. 126.

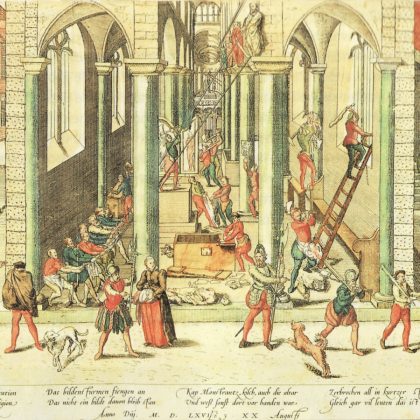

Main image shows Baddesley Clinton, Warwickshire, England

I am researching the Sherringtons. They were nearly all to a man both Lawyers at Gray’s Inn and Aldermen both of London and Wigan. 4 were Mayors of that town and bought up the Manors of UpHolland, Orrel, Boothes and Wardley (still in Catholic ownership today, the Seat of the Bishop of Salford. Francis and his brother John both died in Lancaster Castle for not paying fines for recusancy and deliquency, Catholic and Royalist. Martha his widow conspired with her son also Francis to ensure Wardley at least stayed in the family by selling it to a cousin the Downes family and eventually to the Earls of Ellesmere who still own it but have given it for use to the Diocese. I have traced most of the known ancestry from the early Norfolk/Suffolk 13th C through London and the infamous Sir William Sherrington of Laycock and his time at the Bristol Mint. Through marriage into the Pagetts and Talbots they kept most of their wealth until after the Civil War. My own 4x Gt. Grandmother Molly Sherrington ended up owning a shop in Chorley still a devout Catholic and marrying John Briggs 1792; their son Ralph moved to Blackburn and they were the founding congregation of my church today St. Alban’s Blackburn, first Mission 1770, now a grand 1000 seater church where I am organist. I would be intrigued if you have ever come across this line of my family.