“A Tale of a Man, a Worm and a Snail” – A Book Review

This year a new 275-page book, with 21 chapters, entitled “The Tale of a Man, a Worm and a Snail: The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative” written by Professor Alan Fenwick OBE, with the help of Wendie Norris and Becky McCall, first appeared in January. It is part autobiography, part scientific narrative, with an impressive bibliography. Typical of CABI publishers, the book has a high printed production standard with several colour photographs and schematic graphics that embellish its narrative.

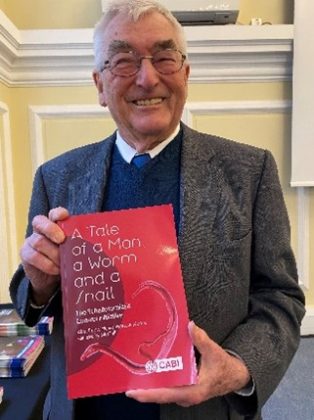

Coincident with this book’s appearance has been an informative companion webinar. This was hosted by the International Society for Neglected Tropical Diseases, alongside a convivial book launch forum at Central Hall Westminster, London on the 26th January, where many who have worked or collaborated with Alan and the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative Foundation (SCIF), convened.

Books like this are not common. I therefore urge those interested in control of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), particularly helminthiases, to read it. Within this book’s mould, I am only aware of two others that each provide a comparable perspective of what it means to have a career in parasitological research or in parasitic disease control. The first is Gerald Esch’s “Parasites, people, and places: Essays on field parasitology” and the second is Ellen Agler’s “Under the big tree: Extraordinary stories from the movement to end neglected tropical diseases“.

Alan’s book, however, carves new territory. It sets its own path, spanning just over five decades of a career devoted to the alleviation of schistosomiasis, as well as vivid descriptions of his formative years leading onto it. Numerous personal anecdotes, often humorous with associated photographs, alongside his and his team’s wider reflections of medicine in the tropics, are weaved therein.

Alan’s story is engaging and enjoyable. For me, it provides a richer set of my personal reflections on the profiles of late and key personnel who have helped shape the field of parasitology in the UK, viz. Gerry Webbe, Rick Davis and Pip Jordan, not forgetting George Nelson, as well as many others living today who define our study overseas, viz. Amadou Garba, Narcis Kabatereine, Mutamad El Amin and Mwele Malacela.

As many will know, Mwele is the current Director of the WHO-NTD Department, Geneva and was national NTD coordinator in Tanzania. She took over the WHO position, succeeding Dirk Engels and Lorenzo Savioli, and their predecessors Ken Mott and Rick Davis. The latter were then responsible for schistosomiasis control even before the terminology of NTDs was conceived. Of course, Alan played, and is still playing, a pivotal role in defining the NTD agenda. This book embellishes his story behind it all well. In an in-depth treatise, he probes the origins of international funding, its evolution and then nuances the roles that several agencies have later played.

Alan’s knowledge of the many international stakeholders over the years is indeed impressive and intimate. He comments upon governmental level agencies, viz. USAID & UKAID and, of course, recounts first-hand his experiences with the first large-scale funding activities of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (B&MGF). In those seminal days, applications for several tens of millions of USD were almost incredulously brief, when judged against today’s applications’ standards. The decision-making processes were then much more rapid. Founded in 2000, B&MGF has now come to dominate the funding landscape for infectious and parasitic diseases. Perhaps not many also know it even financially underpins WHO itself, shaping ESPEN’s current activities, and is donating more funds than many European countries do combined.

With generous B&MGF support, Alan with Michael Reich, secured the instalment of the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI), first briefly at Harvard University, then more long term at Imperial College London (ICL). With the co-ordinating help of the late Bertrand Sellin, SCI was able to support operations in three francophone countries, better balancing the contextual and operational diversity in the 6 countries supported, thereby kick-starting preventive chemotherapy across sub-Saharan Africa more broadly. Essential steps before other governmental agencies ‘bought in’.

Whilst benefiting millions who have had some treatment for NTDs who would have otherwise had none, the B&MGF support also seeded the acorns of future institutional problems. These slowly matured some 15 years later as the funding landscape morphed, being continuously moulded by questions of ‘sustainability’ and its implicit measurements and markers. For example, to continue SCI’s functionality outside of an academic setting, the SCI needed to secure charitable status allowing them to receive significant funds to continue disease control with national-level programmatic implementation.

The transformative steps that Alan, with Wendy Harrison, needed to take are well explained to form the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative Foundation (SCIF), ultimately decamping from ICL to premises in Lambeth, London. In so doing, this then allowed the group to benefit from crowdsourcing funding initiatives such as GiveWell and Giving What We Can. In hindsight, this was a really brave and wise move, especially with recent governmental cuts in official development assistance (ODA) funding and slew of COVID impacts. It has helped position the SCIF outside of the really devastating changes we have seen within several academic institutions, completely dependent upon ODA funding or those unable to weather COVID impediments.

Today, SCIF maintains vibrant research collaborations which can be best defined under the auspices of the Global Schistosomiasis Alliance. Alan’s book provides a really useful stakeholder map where each is given a good airing and nuancing of roles. When taken as a whole, this book is an exemplar of Pasteur’s adage that chance favours the prepared mind, or in his own words “I was in the right place at the right time and fortunate enough to have made friends in the right places”.

Having worked with the SCI team at its inception in 2002 with Howard, Kieran, Cara and Joanne, to me, his inspiring lesson is to pluck up the courage, throughout the many dimensions of one’s life, and seize those opportunities that pass us by and try to do some good. Not so easy when set against the complex cogs and wheels of international aid, academic priorities and on-the-ground control which Alan and his SCIF legacy has had to navigate so adeptly.

After reading this book, a personal question remains and perplexes me for which I ask the help of this readership. What are the statistical odds of the following: Alan and I went to the same secondary school in Newcastle, Gerry Webbe and I play(ed) jazz drums in London, all of us have studied the freshwater snails that transmit schistosomiasis in Tanzania? That we all have worked at the UK schools of tropical medicine is, of course, an evitability but is there something cryptic and formative in the UK and Tanzanian waters that led us each to marvel at these snails, their fascinating, yet devastating, parasitic worms, and also carve scientific careers?

J. Russell Stothard, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine

Editor-in-Chief, Parasitology