What is the extent of a frequency-dependent social learning strategy space?

Traditional models of conformity posit that individuals respond to the frequency of a behaviour amongst a social group only. This gives the impression that conformity functions like a rule-of-thumb to ‘always copy the majority’. This view does not align with recent research which shows that our use of social learning strategies is likely to be flexible. To extend this research, we ask whether an individuals’ decision to conform to the majority of a group will be flexible based on certain social information about the group from whom they learn.

Rather than only considering frequency information, we instead ask whether frequency-dependent social learning strategies are chosen based on up to three orders of social information. This is the highest test of flexibility in frequency-dependent social learning strategies to the author’s knowledge. Specifically, our participants could respond to the following three orders of social information: (i) the frequency of a behaviour amongst a group; (ii) a signal informing our participants whether this group made decisions in a similar or different environment to themselves, and (iii) the reliability of this similarity signal. We consider reliability as signals suggesting a similar group membership do not always correlate with who has the same optimal behaviour as oneself. To illustrate with an example, a recent immigrant to a new social group should conform to the majority- even if they appear different to herself- in order to learn the new local optima of this group. Our experiment modelled both a reliably correct and a reliably incorrect signal. These were informationally equivalent and provided the participants with an equal opportunity to earn pay in our experimental set-up.

We also considered the differences between how asocial skills and social norms, or rules governing our collective actions, are upheld. 302 participants completed either a game against nature, measuring asocial skills, or a coordination game, measuring social norms. Some of these participants could only make in-game decisions based on the three levels of social information listed above. Interestingly, both asocial skills and social norms were learned in a similar manner.

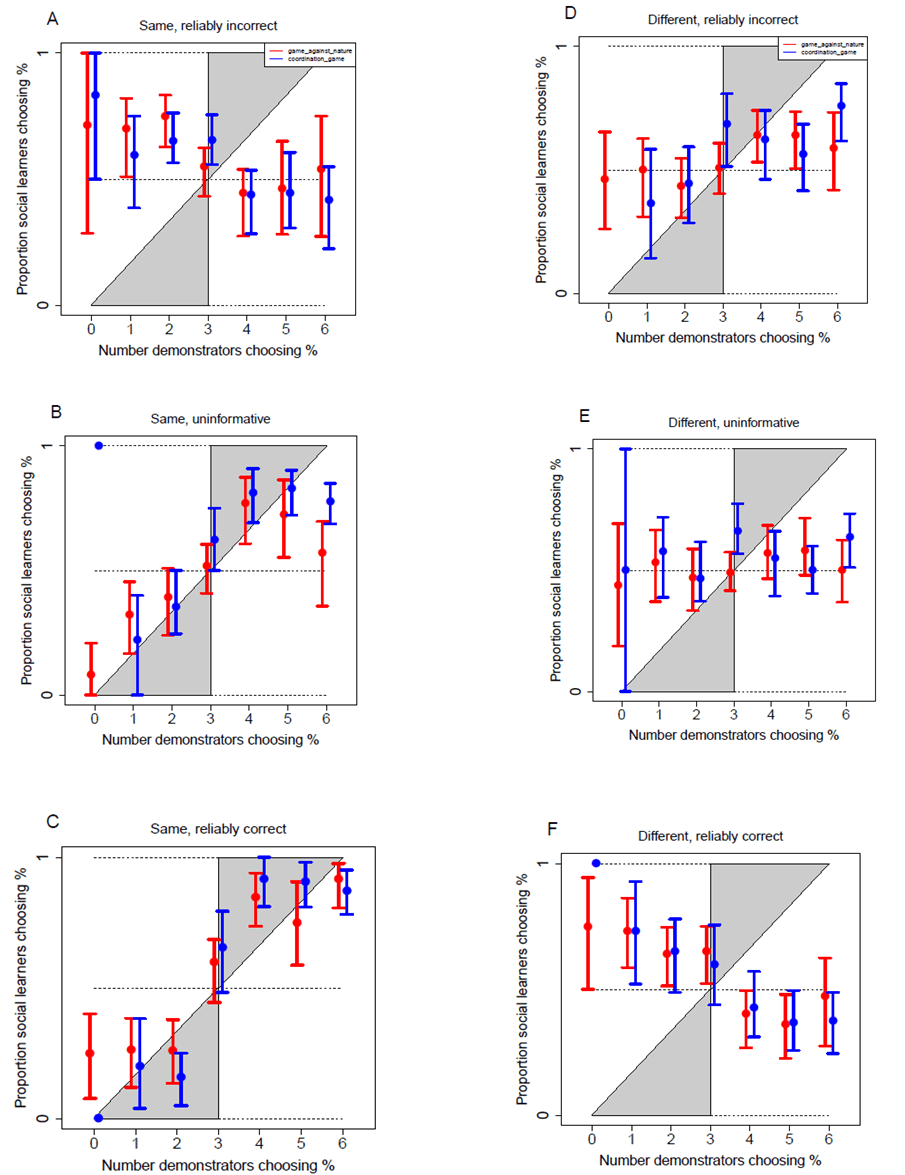

In both games, the participants adjusted their choice of frequency-dependent social learning strategies to (i) frequency information; (ii) similarity signals and (iii) the reliability of these similarity signals. The picture below shows the participants’ responses to each group from whom they could learn. The participants did adjust to frequency information throughout, and they changed their strategies to each level of the similarity and reliability signals. The tendency to follow the majority was strongest around groups of reliably similar others (1C), while the learners followed the minority around groups of reliably different others (1F), and unreliably similar others (1A).

Key :

Figure 1: The social learners’ frequency-dependent social learning strategies in response to each level of the similarity and reliability information. The error bars give the 95% bootstrapped confidence interval clustered on participants, to reflect the multiple observations gathered per participant. Red depicts asocial skill learning and blue depicts social norm learning.

The definition of frequency-dependent social learning strategies, such as conformity, should be extended to consider the fact that learners can update their strategies to three orders of social information, which is more complex than simply responding to frequency information as per traditional models. However, our learners were not fully flexible. During both games, the learners were more likely to answer optimally when learning from groups of reliably similar others. There are trade-offs in the social learners’ choice of frequency-dependent social learning strategies, but these trade-offs are more complex and nuanced than a traditional conformity bias, to ‘always copy the majority’, would suggest.

Author biography

I am now finishing my PhD at Royal Holloway, University of London (RHUL). I was supervised by Charles Efferson and Ryan McKay. My PhD works within the field of gene-culture coevolution. This paper is based on the first chapter of my PhD, where I investigate the flexibility of frequency-dependent social learning strategies. This was an important research question, as conformity is of vital importance to the cultural evolutionary literature. Beyond this work, I am also interested in evolved cognitive biases. My PhD also contains agent-based models, which compare the decision-making of fully domain-general agents to agents with modular cognitive or motivational biases. In line with this work, I also completed a funded EHBEA early-career project with Ryan McKay, investigating the sexual overperception bias (or the idea that men over-infer signs of friendliness as cues of sexual interest in women). This work on evolved cognitive biases also continues from my undergraduate and MSc projects at the University of Lincoln, which was focused on understanding the evolved cognitive biases (if any) which may constrain performance on logic tasks known as the Wason Selection Task.

Ryan McKay also studies the evolution of cognitive biases at RHUL, where he leads the Morality and Beliefs lab. Sonja Vogt and Charles Efferson are based in the economics department at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland. Here, they lead the Policy and Cultural Evolution (PACE) group: a group of interdisciplinary scientists using findings from cultural evolution and economics to help inform long-lasting cultural changes via policy and intervention.

Original publication:

Aysha Bellamy

What is the extent of a frequency-dependent social learning strategy space?

Evolutionary Human Sciences, 13 April 2022, DOI: 10.1017/ehs.2022.11