That is what makes all images too static, for no sooner has one said this was so, than it was past and altered.

I realized I had to free myself from the images which in the past had announced to me the things I sought.

Virginia Woolf began writing the memoir from which I take my first epigraph in the spring of 1939, in the anxious lull before World War II. American Performance in 1976 is set in a similarly febrile, transitional period of cultural history: after the end of Watergate and the Vietnam War; before the AIDS epidemic and the ascendancy of the conservative movement. Longstanding pieties of all stripes had collapsed; new structures of belief had yet to replace them. Theater, dissolving and reconstituting itself repeatedly as we watch it, was particularly well suited to this instability. In 1976 alone, an annus mirabilis for live art, an extraordinary series of experiments captured the era’s restive mood. This book closely reads five of them. In March, Cecil Taylor presented A Rat’s Mass / Procession in Shout, his jazz opera based on Adrienne Kennedy’s play A Rat’s Mass. Meredith Monk’s opera Quarry opened in April. November brought the Robert Wilson/Philip Glass opera Einstein on the Beach and Joseph Chaikin’s production of Kennedy’s A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White. A few weeks later, in mid-December, the Wooster Group invited spectators to an open rehearsal of Spalding Gray’s and Elizabeth LeCompte’s Rumstick Road.

Two of these works, in marking a shift in their makers’ practice, situate their action at equally sharp turning points in modernity. Quarry depicts the deracination of families and other intimate groups during World War II. Einstein traces the no less violent transition from the Industrial Age to the Nuclear Age, ending with an image of an atom-bomb test. Rumstick Road, A Rat’s Mass, and Movie Star, for their part, pursue their ambitions on autobiographical terrain, exploring personal forms of upheaval. LeCompte and Gray probe the suicide of Gray’s mother. Kennedy and Taylor confront no less devastating forms of family betrayal and collapse. All three works reflect a loss of faith in the psyche’s transparency, the durability of kinship, and the meliorative potential of catharsis.

The ruptures in these five pieces summon the fractured modes of expression needed to stage them. The productions’ creators, impatient with the linear forms that have traditionally counted as dramatic, display a visual artist’s attraction to collage and environment, a choreographer’s skill in kinetic narrative, and a poet’s preference for allusive rather than discursive argument. There is ample precedent for these strategies, of course, in the 1960s. By 1976, however, the avant-garde had moved away from the previous decade’s uncritical endorsement of sincerity and naturalness. Yet it had stopped short of the irony that would characterize much vanguard theater in the 1980s and 1990s. Performance in 1976 was poised between one era’s folk populism and another’s austere abstraction.

Seen from the vantage point of nearly fifty years later, the aesthetic betweenness of 1976 seems to have reflected the surrounding political, economic, and cultural climate. Bicentennial triumphalism, peaking in the middle of that hinge year, sounded dissonant in the face of a violent past and an uncertain future. The unceremonious end to the Vietnam War a year earlier cast its shadow over 1976: The year was “postwar” with none of the forward momentum and confidence, much less historical understanding, the term once conveyed. With this hesitancy came skepticism about many areas of civic life. In 1976, the Church Committee, convened by the US Senate to investigate abuses by the CIA, FBI, and other agencies, completed its final report, prompting calls for radical reform. The Pike Committee, in the House, issued its own equally sharp verdict in a report leaked to the press that same year: Excerpts ran in two February issues of the Village Voice. The entire brief, unplanned Gerald Ford presidency, coming to an end with Jimmy Carter’s inauguration in 1977, was an emblem for the country’s anxious period of transition. An unwelcome, if comical, image of that interim came during the September 1976 presidential debate, when the sound system broke down and the two candidates stood nonplussed and mute, taking notes but otherwise inert, failing even to speak to one another for twenty-seven minutes as the cameras kept filming.1 The fact that this dumb show took place in an actual theater – Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Theatre, the nation’s oldest – drives home its pertinence to the period’s equally, but deliberately, unsteady performance.

Having survived multiple eruptions, many Americans spent the latter half of the 1970s waiting for the aftershocks. A “shattered people” (as the political scientist Michael Harrington called them) contended with “continuous, nerve-wracking disequilibria” in these “years in-between.”2 The wariness proved justified. The recession that had begun with the 1973 oil crisis may have technically ended in 1975, but the memory of long lines at gas stations and the lingering traces of “stagflation” – emblems of simultaneous speed and stasis – continued to trouble the economy up through 1979, when a new energy crisis brought new gas lines. The year 1976 turned out to be the start not of recovery but remission – a brief pause throbbing with anticipation.

Different sectors of the American population managed the tension of waiting with different strategies, or (more commonly) failed to manage it. Large portions of the working class had completed their rightward migration under Nixon, but upon his departure no comparable leader took his place. (Reagan would exploit the vacuum. His election in 1980 was the climax of yet another transition, from Republican shame to Conservative renewal.)3 The typical American worker of the late 1970s was, in the words of the labor historian Jefferson Cowie, “a perpetual motion machine of struggle, pushing toward … a fruitless hope.”4 A different but overlapping sector, fundamentalist Christians long removed from the secular political sphere, also sought greater security by entering the democratic hurly-burly. A Newsweek cover story on the eve of the Carter victory declared 1976 to be “the year of the evangelical.”5 At the other end of the spectrum, the progressives who populated the movements for racial justice, women’s rights, and what was then called gay liberation also found themselves at a crossroads. In 1976, the Black Power movement was negotiating a shift in tactics from insurgency to electoral politics. The women’s movement engaged in its own self-questioning that year – after celebrating 1973’s Roe v. Wade decision and, in 1975, the UN’s declaration of “International Women’s Year,” but before the successive blows of the 1977 Hyde Amendment restricting federal abortion funding and the stalled ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment in 1978. Additional strain – over competing visions, principles, and tactics – came from within the movement. Susan Braudy, surveying the different factions in her contribution to a 1976 article titled “What Has Gone Wrong with the Women’s Movement?,” called the year an uncertain “period of transition” and worried about what fear might do to their shared cause.6

The fight for gay and lesbian rights also continued on a landscape riven by upheaval, including internecine conflict. By 1976, progressives had already managed the shift, a few years earlier, from the Gay Liberation Front, with its utopian focus on “freedom,” to the more pragmatic, rights-oriented Gay Activists Alliance. Yet the fault lines in the movement, like those striating the era as a whole, remained stark, and contributed to the era’s uneasiness. In the first issue of Christopher Street, which appeared in July 1976, Charlotte Bunch described the hard-to-reconcile approaches of the “assimilationists,” “reformists,” “socialists,” and “radical feminists” – divisions the publication itself tried to finesse with its wan marketing slogan, “the gay magazine for the whole family.”7 Some in the community were having none of it. The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions – an underground text poised between dream-book and manifesto, self-published by Larry Mitchell in 1977 – names in its title the terrain upon which a defiantly queer identity shaped itself in this period: “between” the Stonewall uprising, in 1969, and the murder of Harvey Milk in 1978. Or, more narrowly, between the removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders in 1974 and the founding of Anita Bryant’s anti-gay “Save Our Children” campaign in 1977. It wasn’t until the first diagnosis of AIDS in 1981 that the movement truly unified, or reunified, seeking justice with newly sharpened clarity. The many uprisings for better healthcare during the epidemic could stand as the future revolution Mitchell envisioned.

The proper relationship between individual and collective freedoms, especially fraught in the context of sexual desire, had become a favored subject of debate by 1976. “How real the sixties were,” Elizabeth Hardwick said, wistfully, in a lecture written that fall (delivered in January 1977, and later published as “Domestic Manners”), after she remarked on “the sudden obsolescence of attitudes and styles just past, styles that collapsed or scattered into fragments … casualties of every spiritual and personal nature.” The 1970s, or what the decade might have become, was also lost by then: “The 1970s have passed their zenith. Did they take place – this handful of years – somewhere else, in another land, inside the house, the head?” Yet “even drift has its direction,” Hardwick insisted, and for her that direction was, fatally, toward the self.8 Along with Tom Wolfe, who named “The Me Generation” in New York magazine in August 1976; Christopher Lasch, whose essay “The Narcissist Society” appeared in The New York Review of Books in September; Richard Dawkins, who published The Selfish Gene later that fall; and Richard Sennett, who published The Fall of Public Man in January 1977, Hardwick diagnosed an inward turn in a citizenry that supposedly overvalued immediate needs and pleasures, ignored history, and abdicated responsibility for the future. Diane Johnson, covering the Patty Hearst trial for the New York Review of Books in April 1976, anticipated and tacitly gauged the force of these critiques while defending her subject against them. Johnson used a theater metaphor to make sense of the sensational proceedings, which had begun in February: It was “a modern play – qualified, ironic, and absurd,” in which “it was hard to know whether it was about crime, as billed, or about politics, as it seemed.” Ultimately, she showed, it was about morality: “the audience [went] home happy” after Hearst’s conviction, smug in its certainty that “the American system works” in punishing the rich, the revolutionaries, “the sexually ‘immoral,’ people who smoke dope, spoiled brats, … undutiful children and rebellious women.”9 The visionary radicalism of the 1960s, in the eyes of Hearst’s self-righteous prosecutors and jury, had devolved to 1970s self-dramatization. For certain wary theater artists who themselves claimed the private sphere in 1976, all these writings would have confirmed their own sense of autobiography’s dangers: Their most resonant performances displaced or veiled a self they only seemed to exalt.

Another dismayed observer of the mid-1970s landscape issued an even more severe judgment on the cultural moment. Hannah Arendt, in a “Bicentennial Address” entitled “Home to Roost” (her last published essay before her death in December 1975), also used a theater metaphor to acknowledge that “no one was prepared, not even after Watergate, for the recent cataclysm of events, tumbling over one another, whose sweeping force leaves everybody, spectators who try to reflect on it and actors who try to slow it down, equally numbed and paralyzed.” She had in mind not just the fall of South Vietnam but mid-1970s policy “disasters” and “debacles” in Cyprus, Turkey, Portugal, Greece, Italy, England, and India: “we may very well stand at one of those decisive turning points of history which separate whole eras from each other.” In the chaotic and unmoored new epoch, she argued, US policymakers emulated “the seemingly harmless lying of Madison Avenue” and rushed to disseminate “an image which would convince the world that it was indeed ‘the mightiest power on earth.’” Her essay reminds artists who themselves traffic in images – including, in 1976, a cohort of theatermakers attuned to verbal misdirection and, more generally, seeking alternatives to narrative-bound texts – that visual language is no less vulnerable to dishonesty. “For many years unpleasant facts were swept under the rug of imagery.”

Arendt, a refugee from Nazi Europe, brought to her diagnosis of Bicentennial malaise her knowledge of earlier eras of deception and insurgency. She also urged historical understanding on her audience. “While we now slowly emerge from under the rubble of the events of the last few years, let us not forget these years of aberration.”10 It was with similar convictions, or the memory of being guided by them, that Vivian Gornick traveled to Harlem in early 1976 to attend Paul Robeson’s funeral – the actor, singer, and activist had died on January 23 – and felt an unexpectedly enveloping sense of loss. “A fragmented sense of things filled the space where once there had been large and coherent meaning,” she wrote in the Village Voice, suggesting that Robeson’s death, decades after he stood with the left on countless barricades, had exposed the inertia of present-day opposition. Recalling his commitments from the Spanish Civil War through the McCarthy era, Gornick wrote, “He … had outlived the context which had given his life heroic dimension. All around lay only sentimental ashes.”11

“Ashes,” “rubble,” “scattered fragments”: The images favored by these three essayists may be metaphoric, but in the mid-1970s landscape with which they were most familiar, New York City, the ruin was real. American Performance in 1976 is as much about a particular place as it is about a particular time. In 1976, the fiscal crisis that had paralyzed New York a year earlier was coming to an end, but a twenty-five-hour citywide blackout in 1977 suggested that the darkness had yet to lift completely. Crime peaked in New York in 1976, overwhelming a police force crippled by successive budget cuts; the same scarcity afflicted fire departments, sanitation services, and building maintenance companies. Trash clogged many city streets; streetlights that burned out stayed dark; the parks were overgrown; public libraries, schools, and daycare and senior centers were overcrowded or understaffed, and thus had to reduce services when they weren’t shutting down at record rates. A section of the West Side elevated highway that had collapsed in 1973 was still unrepaired and incompletely cleared three years later. In May 1976, the entire City University of New York system closed briefly to stave off bankruptcy; the next month, it began charging tuition for the first time since its founding in 1847. To manage all these crises, as the historian Kim Phillips-Fein has shown, the city shifted its priorities from the working and middle classes to business and investor interests. Liberalism, rather than resisting the pivot toward the wealthy, abetted it – a wrenching transition that was just one of many in this hinge era.12 Class tensions were not the only source of strain in 1976. Washington Square, in Greenwich Village, erupted in racist violence in September, when a crowd of largely Irish- and Italian-American men and boys, acting on the pretext of “cleaning out” the park of drug dealers and junkies, attacked with pipes and baseball bats “anyone who was Black or brown,” as the New York Times reported.13 More than thirty-five people, including a pregnant woman, were injured; one person died.

In such a climate, it was shocking but unsurprising that when the city was being terrorized by David Berkowitz, whose murderous rampage as “Son of Sam” had begun in July 1976, he described himself in terms that would be instantly legible to others who had navigated this blasted and hostile urban landscape. “Hello from the cracks in the sidewalks of N.Y.C.,” Berkowitz wrote to the New York Daily News columnist Jimmy Breslin the following June. “Hello from the gutters … the sewers … the ants that dwell in these cracks.”14 His letter was the macabre antiphonal response to other writers’ hymns to fugitivity and upheaval. In a 1975 lecture, Richard Schechner, director of the Performance Group, suggestively mapped the “crease phenomena” of contemporary New York: “areas of instability, disturbance, and potentially radical changes in the social topography.” The most interesting theaters, he added, thrive in them, “living off the leavings, like cockroaches.”15 As performance theorists gravitated to creases, the visual art world staked a claim on “edges.” In three influential essays published in Artforum in 1976 (later published as Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space), Brian O’Doherty focused attention on, and troubled, the border between an artwork and the wall it hangs on, and between the “sanitized” gallery and the “bacterial” street. O’Doherty treated these hitherto invisible or taken-for-granted edges as “structural units” awaiting exploitation. Art “needs the sound of traffic outside to authenticate it,” he argued, urging us to consider what stimuli we evade (and what ideology we uphold) when we “encyst” works in white cubes.16 Both Schechner and O’Doherty were offering closely argued versions of principles that Larry Mitchell would soon be endorsing, with verve and rococo lyricism, in The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions. There were opportunities to be seized, Mitchell insisted, on the forgotten margins, in the overlooked interstices, amid ongoing entropy and decay, and during the rough, illegible transitions between golden ages. All became fertile ground for new, hitherto unauthorized forms of identity, affection, and – most pertinent to this study – creativity. “The faggots and their friends live the best while empires are falling,” Mitchell declared. “In the spaces created by ruined buildings the queens have made a dazzling new world.”17

The paradox is key to understanding the period. Conditions that were oppressive to the body politic – fissures and fractures, unrelieved flux, suspendedness and its accompanying vertigo – were, for the era’s artists, often desirable, even ideal, attributes of their practice. In the breach between the 1960s and 1980s, they worked to undo the ideological rigidity and strenuous sincerity that had constrained art in earlier eras. They also resisted subscribing to any new orthodoxy for as long as possible. In their work, they chose detachment over unearned intimacy, incomplete rather than frozen form, opaque over transparent identity, promiscuous (or ecumenical) attention over singular focus, and dedication to objects over abstractions (but also to tasks over objects). An impure theater of operations, whatever the art form, was preferable to an immaculate one. A practice that exploits rather than resists contingency seemed to promise a livelier art. “There was no style for the decade,” wrote Edmund White of the 1970s in general, not without admiration. This absence pointed to other useful failures. “For language to stay honest,” White continued, “it must start from the beginning each time. Nothing can ever be fixed in words – when it is, the fixative kills the butterfly and stills its most distinctive characteristic, motion.”18 Or, as John Ashbery said more simply in “Houseboat Days” (a poem first published in February 1976), the artist’s and reader’s imperative is to “stay, in motion.”19 The comma in that last phrase, mandating a pause after “stay,” helps us manage the contradiction between Ashbery’s first and last words.

He was lingering in an interval that attracted several other writers in and around 1976. Elizabeth Bishop’s Geography III, published that year, opens in an interim – the speaker of the book’s first poem is “In the Waiting Room” (as the poem is titled), counting the “three days” until she turns seven – as does James Merrill’s “The Book of Ephraim” in Divine Comedies, also from 1976. “My subject matter / Gave me pause,” he writes, stopping the poem he just started. Later, another interim will prove more stimulating: A Ouija board that generates much of the poem’s language is a zone “between one floating realm … / And one we feel is ours.”20 A differently hallucinatory writer, Constance De Jong, cultivated her own roving mode of attention on deceptively more solid ground. In her novel Modern Love, composed between 1975 and 1977, she depicts her era as “nothing but a separation; an empty space between two places,” like the “January night” in which she writes, thick with “a darkness that has substance.”21 For Renata Adler, those same gaps required fearless leaps if she, and we, were to survive them. A passage from her episodic 1976 novel Speedboat describes how the title vessel “scudded” and “bounce[d]” over the waves, jumping the intervals, not resting where it lands. It’s a sequence that sets the tempo for the narrator’s life – “there are situations in which you are not entitled to stop” – and gives the author a metaphor for her preferred style: “the sort of sentence … that runs, and laughs, and slides, and stops right on a dime.”22 (Even that stop is temporary: Adler and other mid-1970s novelists were determined to represent “lives … that do not conform to the finalities of the novelistic,” according to Elizabeth Hardwick.)23 James Baldwin, in his trenchant 1976 book on film, The Devil Finds Work, names a sharper interval. He traces his viewing pleasure and pain to the experience of waiting for the curtain to rise (“you are, yourself, suspended … mortal”), and then to “the movement on, and of, the screen … which is something like the heaving and swelling of the sea” – movement that casts into relief the surveilled entrapment of the young Black spectator: “we wished, merely, to be free to move.”24

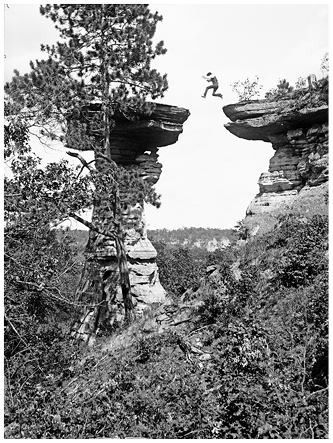

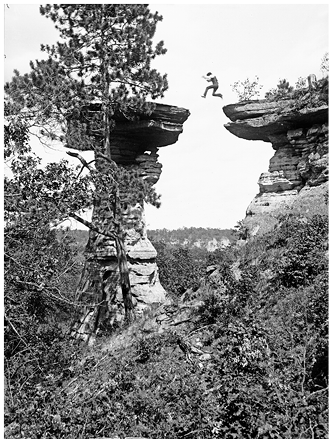

All these energies come together in the early prose of David Wojnarowicz, who reflected the spirit of the times when he asked the publisher of Sounds in the Distance (1978) – his book of monologues by truckers, rail-riders, hustlers, and other itinerants, each of whom “needs some kind of motion” – to put on the cover an 1886 photograph of a man leaping between two cliffs (Figure I.1).25

Figure I.1 H. H. Bennett: Leaping the Chasm (1886), from David Wojnarowicz, Sounds in the Distance (1978).

*

In American Performance in 1976, I aim to show how art in a transitional era must be understood as continually transforming – leaping between cliffs – and thus eluding our ability to contemplate it, even as it “stays” just long enough to capture our attention. This may be counterintuitive for those trained to regard 1970s vanguard performance as the “Theater of Images.” That phrase, coined by Bonnie Marranca in 1976 and later serving as the title of the most influential study of the era’s experimental theater, directs our attention to the stage’s tableaus, panoramic vistas, and mesmerizing objects, to the actors’ sculptural poise, and to a pictorial rhetoric that often takes the place of narrative, characters, and conversational language.26 Yet as my chapter title, “All Images Too Static,” implies, I think it is no less appropriate, and perhaps truer to the nature of all time-based art, to attend instead to how live performance is always rescinding the visual pleasures it offers.

The five pieces I focus on, for all their many seductions, interrupt or impede our surrender to their images. All emulate the poise of the plastic arts – subsuming character and actor in the tableau, triptych, photograph, and landscape – yet release the most energy when those compositions tremble, crack, or collapse, often resulting in what one artist in this era called “visual removal.”27 A Rat’s Mass / Procession in Shout, Quarry, Einstein on the Beach, Movie Star, and Rumstick Road are suffused with pathos yet wary of “expression” (in the pejorative sense that the gallerist Helene Winer, director of Artists Space from 1975–1980, intended when she said, “expressionism embarrasses me!”).28 They bear their makers’ unmistakable signatures yet bar access to their interiors, even (or especially) at their most autobiographical. All the original productions featured performers – Sheryl Sutton, Lucinda Childs, Meredith Monk, Spalding Gray, Libby Howes, Jeanne Lee, and Robbie McCauley – whose commanding presence derived from being abstracted or neutral: Their diffidence was charismatic. This was perhaps the only credible form of subjectivity after 1960s sincerity had dissolved under 1970s skepticism. To many in the decade, a transparent character risked tendentiousness, shallowness, or simply bad taste. The punk musicians Richard Hell and the Voidoids saluted those who would resist it when, in 1976, they sang of “The Blank Generation.”29 In a different idiom, Bob Dylan himself seemed to acknowledge opacity’s ascendancy when, during the 1975–1976 tour of his Rolling Thunder Revue, he regularly performed in whiteface, occasionally doubling the already redundant disguise with a clear plastic mask. “When someone’s wearing a mask, he’s going to tell you the truth,” Dylan said by way of explanation, although he was pessimistic about sincerity’s chances in a period when “people had lost their conviction for anything.”30 (Not every artist in 1976 shared the commitment to affectlessness. The artist Joyce Kozloff spoke for the other camp in two influential manifestos, “Negating the Negative (An Answer to Ad Reinhardt’s ‘On Negation’)” and “On Affirmation,” both from 1976. They announced a countermovement, Pattern and Decoration, that was “anti-blank,” “anti-cool,” and “anti-detached,” and that unapologetically endorsed the “ornamented” and the “colorful.”31 In the theater, Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company was itself anything but “blank,” even as it laid claim to its own interstitial “creases.” As Ludlam said in 1978, “the two great opposing poles right now are avant-garde conceptual theater and the search for the new realism, but they have the same literalness. What’s in between is expression, which is what I’m doing.”32)

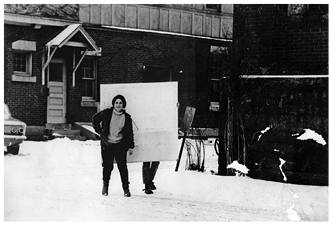

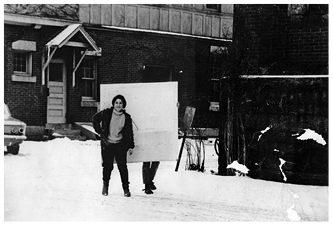

The many narratives of non-expression – some artists appearing most themselves when unselved – are anticipated in a single image, a snapshot from Elizabeth LeCompte’s undergraduate years (Figure I.2). A Skidmore College friend photographed her and another woman in 1965, as LeCompte carried a large piece of homasote board across a Saratoga parking lot. (It could be a set piece, part of an artwork, or simply a dorm-room enhancement.) The panel shields LeCompte’s entire face and upper body – she is visible only from the knees down – yet for that very reason it makes the photograph uncommonly revealing. The portrait announces the commitment to theatrical deflection, to cultivating centrifugal or peripheral seeing, and to finding depth on a work’s surface that LeCompte along with the other artists I discuss would fulfill a decade later.

Figure I.2 Elizabeth LeCompte (obscured) and Diane Burko, Clark Street, Saratoga, NY, circa 1965.

Access to a subject’s interiority, that of the artists or of their onstage surrogates, isn’t the only thing these works impede. They mount a direct critique of other ways of seizing knowledge. Kennedy and Taylor – each representing the churning rhythms of obsessive minds – trouble reductive ideas of racial identity and trace the disordering effects of sexual violence. Quarry argues for an approach to history that recognizes its fractured poetics, the surging persistence of the past, the muteness of its artifacts, and the remoteness of consolation. Einstein on the Beach is equally clear-eyed about the limits of scientific knowledge. The mathematicians, judges, chalkboard scribblers, and newspaper readers who fill the opera seek information effortfully, rarely achieving clarity in a continuously shifting mise-en-scène. The same doubt – in this case about psychological availability and the promise of catharsis – fills Rumstick Road. At its end, LeCompte and Gray acknowledge their helplessness before an event as occluded as suicide. They measure (but resist bridging) the gaps between intimates, and repeatedly fail at coaxing meaning from a diffident archive. They are, in this account, forever positioned between loss and recovery, bending toward but never achieving comprehension. In this, they reflect the literal and figurative imbalance theatricalized in all five productions.

*

Drawing on archived and privately held production materials, video recordings, artists’ diaries and notebooks, my attendance at live performances and observation of rehearsals, and my interviews with the creators and their collaborators, American Performance in 1976 lays out the poetics of this moment. I recognize the challenges in identifying, and isolating, a single “moment.” Artists didn’t pivot in unison from one mode to another in January 1976, nor did they all shift again twelve months later. Qualities that characterize performances in this year had been gestating earlier in the decade (and even before); they continued to inform some artists’ practice years afterward. Yet as Virginia Woolf put it in anticipating objections to her famous claim that “on or about December, 1910, human character changed” (from “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown,” 1924), “I am not saying that one went out, as one might into a garden, and there saw that a rose had flowered, or that a hen had laid an egg. The change was not sudden and definite like that. But a change there was, nevertheless.”33 While 1976 is not the decade’s only culturally significant year, it does offer a window on the period: Through it one can see especially clearly an aesthetic turn (and stakes of that turn) in American vanguard theater. By that year, a transition that had begun slowly at the start of the decade was in full swing. Bread and Puppet Theater had moved from New York City to Vermont in 1970. In 1972, Yvonne Rainer had begun a thirty-eight-year hiatus from choreography to concentrate on filmmaking. Joseph Chaikin’s Open Theater had closed in 1973. The Living Theater had left for an eight-year stay in Europe in 1975. That same year, André Gregory had dissolved his own theater, the Manhattan Project. The Performance Group, under the direction of Richard Schechner, also had begun to splinter in 1975 (the emergence of the Wooster Group was one result) and closed for good five years later. The five productions I’ve singled out from 1976 took shape in the newly vacated or uncertainly shifting spaces revealed by these and other changes. By reading them closely, and by putting them in the context of wider artistic developments, I hope to offer tools for measuring the effects of that transition, and for assessing other works from the decade.

And from 1976 itself. “That’s where we are right now! IN BETWEEN!” The character Tympani’s blaring announcement in Sam Shepard’s Angel City – an apocalyptic Hollywood drama that premiered in San Francisco two days before the Bicentennial – suggests that a wide array of artists, even those aesthetically remote from “my” figures, felt a similarly agitated sense of intermediacy that year. Tympani’s employer, a movie executive trying to explain the malaise affecting his business (and, implicitly, his audience), maps this space further, in terms that will now sound familiar: “No big, major world war. No focus. … No focus, no structure. No structure spells disaster.” In this formless, unfocused interim, film itself seems to exacerbate the “disaster.” It reduces every crisis to a commodified image and steals the souls of the image’s consumers: “I look at the screen and I am the screen,” says a woman surrendering to her celluloid dreams. “I’m not me.” (Shepard’s Suicide in B♭, another 1976 premiere, takes this anti-solipsism further. Its shape-shifting musician-protagonist, the playwright’s surrogate, doesn’t recognize himself, feels “already dead,” and yearns to “start over.”)34

Shepard’s “in between” is David Rabe’s mid-air, the terrifying space through which a paratrooper falls. The title of Streamers, which premiered in New Haven in January 1976, refers to the parachutes that don’t open. An equally anxious waiting room is the stage itself: Rabe sets the action in a US barracks where soldiers await word of their inevitable deployment to Vietnam, their fear sharpening and seeking a valve before turning violent, as it does here. Ntozake Shange figures yet another form of intermediacy in for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, which opened at New York’s Public Theater that June. (Earlier versions had appeared at the New Federal Theater and Studio Rivbea.) “We’re right in the middle of it,” says the Lady in Blue, one of six women who “deal wit emotion too much” and thus hope to “think our way outta feelin.” She and the others arrive at a zone between pain and numbness, claiming their “right to sorrow” but also asserting mastery over it, becoming virtuosos at what the Lady in Red calls “livid indifference.” Her phrase acknowledges the contradictions of the decade. For Shange, movement ensures that the women’s cool demeanor never freezes into affectlessness. (They “dance to keep from cryin” but also to “keep from dyin.”) In this “choreopoem” (as Shange calls it), “there is no me but dance” – a strong deferral of private pathos in a work that deceptively seems to indulge it.35

Worlds away from Shange in aesthetic and affective priorities, David Mamet expresses a related skepticism about the self – or more precisely, about its durability and grandeur – in his own work from 1976. American Buffalo is set in a landscape of waste – a junk shop cluttered with a culture’s flotsam and jetsam – embedded in a wasteland: “There is nothing out there,” says one character, Teach, gesturing to the world beyond the shop’s doors. Unmooring him further, time has stopped: “I took it off,” he says of his watch, “when it broke.” That emptiness and sense of suspension – a darker variation on the unmarked interims and nonprogressive narratives created by other writers, and no less serviceable as an image for an inchoate era – attracts equally empty, or contingent, residents: “I’m coming in here to efface myself,” says Teach, asking an offended question without a question mark, as if he hoped to resist erasure by preemptively welcoming it. Here, as in for colored girls, viable and resilient identity will come only through action – a release that, in this play, become less likely the more the characters keep talking, revisiting past slights, consulting books, and fetishizing the shop’s many objects. Even after they agree that “action talks and bullshit walks,” they spend their time plotting a robbery they never perform, as alert with anticipation and uncertain of direction as the 1976 audience watching them.36

Two last productions from this year – unnoticed and unheralded by many; angrily condemned by a few – succeeded in supplanting the singular image (or narrative, or situation) with its prismatic and disorienting variations, or simply with breathless activity that deliberately moves in circles. Ed Bullins’s Jo Anne!!!, its three exclamation points suggestive of the high pitch at which it unfolds, is explicit about its purpose. “People wouldn’t understand,” says the title character, an imprisoned Black woman, to the white jailer who raped her (and whom she kills). “They’d look at your lying images and think there’s some truth in your story.”37 Bullins scripts four counter-narratives of their encounter to loosen any one version’s – one image’s – claim on our uncritical attention. (Even before the play began, audiences learned to watch how they watch it. They passed through metal detectors and were electronically frisked before they entered the Theatre of the Riverside Church, now figured as a space under surveillance.) The characters in Wallace Shawn’s differently scandalous A Thought in Three Parts (originally produced as Three Short Plays in a November Public Theater workshop) make hairpin turns from lust to rancor to repulsion, only to discover they can never shake off ennui or fear. In the first of its three parts, “Summer Evening,” set in a hotel room, two actors (as a stage direction insists) “speak very fast, maybe much faster than people really speak…almost overlapping” and without pausing. The desires they name – for a pretty dress, a piece of toast, a hug, their partner’s death – matter less than the fervor of their longing. The second part, “The Youth Hostel,” strips individual sex acts of their erotically or emotionally transporting properties. The four characters who industriously copulate and masturbate maintain studiously flat affects, regardless of what they do or submit to. Bromides about “liberation,” convincing less than a decade earlier, would, if applied to this world, sound sentimental if not specious; “self-fulfillment” first requires confidence in the self’s substance, something more than this scene’s purposeful refusal of sublimity allows. Despite the many facsimiles of release, true catharsis – sexual or psychological, ecstasy or rage – is in fact forever deferred, a state Shawn names directly in the third part, “Mr Frivolous,” in which a solitary, tired, and disillusioned man says, “I lie here waiting. Waiting. Waiting. Now. Now. Now. Now.”38 The pulsing present tense seems to measure a year-long interval.

All these plays, despite their narrative and tonal differences, recur to a shared set of formal concerns characteristic of the era’s performance. Spaces are temporary, marginal, contingent, and transitional. They are marked by signs of lives lived elsewhere, or deliberately unmarked: hotel and youth hostel, barracks, junk shop, jail cell and courtroom, and other vague “middles” and “in betweens.” Characters, conditioned by such liminality, are equally unfixed. Dubious of spontaneity, they monitor their impulses and disclosures; many utterances prompt the speaker’s revision, retraction, or self-silencing. The mise-en-scène itself seems to embed its own critique. To look at it (as character or spectator) is to be held at a distance and, at times, to confront ethical and moral doubt about our looking, as if any act of attention risks violation. Dramatic structure is stuttering or spasmodic, and favors recurrent cycles, anti-climaxes, diminuendos, or, often, duration over progress. Yet stasis is deceptive. In fact the action simmers with contained energy, or (in what amounts to the same thing) erupts and subsides continuously, or lurches forward and then reverts, postponing its arrival at a destination.

*

This last quality – performance’s fever, its acquiescence to time’s disheveling pressure – is especially pronounced in the work of the era’s more emphatic experimentalists, those who, by resisting a text’s promise of stability, interrupt its narratives and multiply its meanings (when they write or stage narratives at all). These artists, themselves responsible for another large number of signal works in 1976, further expand the context for those discussed in the chapters ahead. It’s worth pausing over some of these landmarks, if only to complicate our definition of the mid-1970s avant-garde. These other works, like the ones I will discuss in depth, are hardly outliers but instead feed an alternative mainstream.

It was already flowing as the year began. Richard Foreman had opened Rhoda in Potatoland, one of his most important plays, at the end of December 1975; it would run through the following February. In its chronic self-questioning and engineered collapse, it stands, shakily, for the year’s restlessness. As its title suggests, it is a travel play of sorts – characters “ventured forth,” as a voice says at the start, and “then they ventured forth again.” Yet the line’s redundancy confirms that these travelers are stuck in an endless loop: Destinations recede as their itineraries, the sights dotting them, and the sightseers themselves submit to perpetual rearrangement. “A space going on in my body,” Rhoda says at one particularly disorienting moment. “A place growing in my mind.” Spaces go; places grow; neither simply, passively, is. Foreman’s set literalizes that agency. Throughout the performance, his long and narrow loft on lower Broadway deepened and contracted, narrowed and strained at its edges. At repeated moments, an upstage wall fell to the floor and the scene’s horizon suddenly grew more distant. (Moments later, it closed in again.) Actors lurked partway in the wings, as if they were pulling apart the stage’s margins to reveal more action, unless they were straining to contain it. Tableaus fractured; characters wielding large tubular objects measured distances that defined and controlled their otherwise ambiguous relationships, only to redraw the stage geometry minutes later. The seemingly unstoppable architectural revisionism was the visible evidence of psychological and intellectual restlessness. In compulsively restarting the play (its subtitle is Her Fall-Starts), Foreman exposed the limits of his and, tacitly, our knowledge, and envisioned new hermeneutic strategies. “Everything up to now was recognizable,” the Voice says. “Now … a different kind of understanding is possible.” (Even the preference for motion over stasis is subject to second thoughts. A character says of Rhoda, “she wanted to be like architecture, not like dancing.”)39

Later in 1976, soon after Rhoda in Potatoland closed, Foreman published an essay in Performing Arts Journal (PAJ) that, without naming his play, distilled it to a principle. It also crystallized the ambivalence over visuality he shared with his experimentalist peers. “The art experience shouldn’t ADD to our baggage, that store of images that weighs us down and limits our clear view to the horizons,” he declared in “How to Write a Play.” It “should rather (simply) ELIMINATE what keeps us moored to hypnotizing aspects of reality.”40 In a separate essay for the inaugural issue of October, the influential art journal that, like PAJ, began in 1976, he distilled further. He aspires to an art of “perpetual motion” that is always “shifting…the frame of reference,” he wrote in “The Carrot and the Stick”: “KEEP GOING!”41 Richard Schechner, for his part, published an essay this same year that also challenged the magnetized engagement long thought to be the most desirable form of spectatorship. In “Selective Inattention” (from the first issue of Performing Arts Journal), he identified – and celebrated – the drop-in, drop-out mode of watching very long or very dispersed productions by Wilson, Bread and Puppet, and the choreographer Douglas Dunn. Audiences for these works came and went at will, no longer in the image’s thrall yet somehow possessing it even more fully. This was “distanced looking at rather than being swept away by” a show.42 All these desires – to keep spectators from being “hypnotized” or “swept away” by perpetually rerouting the stage action and empowering their critical seeing – animated Foreman’s other major production this year, The Threepenny Opera, presented at Lincoln Center. It was a spectacle of sharply angled, off-balance tableaus, aggressively frontal choruses, and one quicksilver, seemingly double-jointed presiding dancer, all arranged on a stage cratered with black holes and backed by fathomless shadows. “Why was everybody moving all the time?” complained one irate spectator, astutely, in a letter to the producer Joseph Papp. “Why were things opening and closing and going up and down?”43 She wasn’t having it, but other spectators apparently enjoyed the perpetuum mobile: The production was a surprising commercial success.

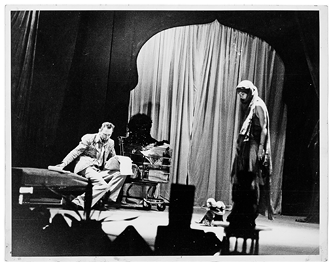

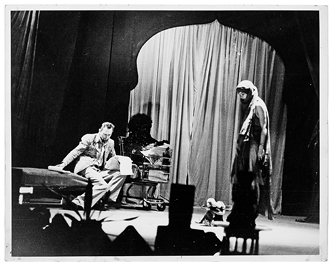

In his notes to Threepenny, Bertolt Brecht had invited audiences to see his text as “a foreign body within the apparatus” of theater and to judge the effort to assimilate it.44 This metabolic imagery – dramatic action as digestive process; performance as peristalsis – would seem even more appropriate to other productions in 1976. They moved in purposeful cycles, or achieved a fervid, humming intensity in near-stillness, or charged the silences with the pressure of the unsaid. Actors themselves became sites of minute and painstaking mutation. (“Mutate or perish,” said a husband to his wife in Edward Albee’s Seascape, which had premiered a year earlier.45) They approached the status of organic objects, obedient to systems that broke down subjectivity into its component impulses and reactions – that reduced emotions to their cellular forms and behavior to separate impersonal gestures. No 1976 work better displayed this process that Jack Smith’s The Secret of Rented Island, his adaptation of Ghosts – an improbably convincing embodiment of Henrik Ibsen’s narrative of decay (Figure I.3). At the start of its run, on Halloween, it ran ninety minutes; by its closing night several weeks later it had metastasized to five-and-a-half hours. One felt it was still not finished even then, and never would be: It thrived in a state of continuous, non-ultimate collapse, every nadir revealing another depth still unsounded. Or, alternatively, it was always finishing, with both origin and period nowhere in sight. Audience members, never more than a handful, adjusted their viewing styles accordingly: They often arrived late, fell asleep, or left early. Those who stayed remember it as a triumph of what Foreman, a dedicated admirer of Smith’s work, had once called the latter’s “granular stasis” – the phrase suggestive of a vibrating landscape or a darkening weather system, one filled with foreboding, imperceptibly but relentlessly transforming.46

Figure I.3 Jack Smith: The Secret of Rented Island, Collation Center, New York, 1976. Pictured: Jack Smith, Ron Argelander (in shopping cart), unidentified actor.

“Everything in it is wildly climactic,” Smith had once said of Ghosts, explaining the play’s appeal.47 But if every moment is climactic, none is. In his staging, Smith broke the back of the play’s mounting tension. His multiplying crises had no obvious source and didn’t settle into clarifying denouements: The sense of strained lassitude or hectic entropy (oxymoronic states that were Smith’s element) was, by design, unrelieved and unvaried. The result was no less suspenseful. In every performance, set pieces broke, but the actors maneuvered around the rubble. Smith, who played Oswald and directed the action from the stage, regularly lost pages from his unbound script. As they fluttered to the floor before he could enact them, he simply, if crankily, recalculated the narrative’s route. An audio recording of other dialogue, all spoken by a phlegmatically slow Smith, was largely unintelligible, but, reduced to near-guttural sound, it expressed the essence of Ibsen’s constricting, choking fear. Like the sound of wind and rain that also drowned out words, the text was an atmospheric element, something to contend with or simply withstand. Individual expressiveness, even apart from speech, was always in doubt. Mrs. Alving, played by a man, was confined in a shopping cart throughout the production; stuffed animals stood in for the supporting roles. Smith himself stood (or, more precisely, reclined, on a divan) between mastery and surrender. At the end, when, in Ibsen’s text, the dying Oswald famously says, “Mother, give me the sun,” Smith instead asked her to “play the Doris Day record.” The song “Secret Love” filled the stage as he faced his end. In fact, The Secret of Rented Island had seemed posthumous from the start, always on the verge of being absorbed by the earth, its secrets safe. (We should have expected that fate all along: Soon after the performance began, Smith announced he was wearing “Natur-Glo Mortuary Cosmetics.”)48 The production clarified the forceful equivocations shaping much of the era’s theater. Its twin refusals to start and end – what Michael Moon aptly called its “announcing-and-deferring-performance”49 – withheld a fixed and thus (Smith’s great fear) easily seized and stolen image. His performance was a belligerent affirmation of Charles Ludlam’s principle, asserted in 1975, that “the theatre is an event and not an object.”50

In a different idiom, inexorability also characterized the four productions by the Mabou Mines company that appeared in 1976, all of which anatomized the effort to resist inertia and transcend gravity. Lee Breuer’s mesmerizing staging of Beckett’s The Lost Ones, which had premiered the year before, returned to the Public Theater for an extended run in January and February. The actor David Warrilow manipulated dozens of tiny plastic toy soldiers – the title characters – in a chamber piece that, like The Secret of Rented Island, testified to one man’s strenuous desire to command a shrunken, claustrophobic landscape – to script rather than suffer its cycles of life and death. “Restlessness at long intervals suddenly stilled,” as Beckett put it, in what could stand as a summary of the performance. The work’s “searchers” (as its figures are known) – some “perpetually in motion,” others “com[ing] to rest from time to time all but the unceasing eyes” – move (or rather, are moved, as Warrilow handles them with fierce concentration and reverential intimacy) around a cloistered cylinder in “fits and starts” – “a few seconds and all begins again.”51 That same sense of a pulsing, agitated present tense could be felt at the company’s staging of Beckett’s radio play Cascando later that spring. Its central figure is a writer who compulsively starts a new story the minute he finishes an old one – “couldn’t rest … straight away another” – yet also can’t finish the story he’s now writing: a negative image of the commitment to ongoingness celebrated elsewhere in 1976 performance. In the Mabou Mines production (JoAnne Akalaitis’s first as director), the characters seem suspended in amber yet hardly idle: Writing isn’t their only repetitive, non-teleological behavior. Gathered around a table, they knit, build a model ship, dance, rock in a rocking chair, and, throughout, pore over maps in preparation for trips they never take, “heading nowhere … heading anywhere,” as Beckett writes. For all their busyness, they spend their time summoning changes that don’t happen, or that happen so imperceptibly they don’t disturb the status quo. The effect was heightened by the recursive music commissioned from Philip Glass, a co-founder of the company – a piece for solo cello played live onstage by Arthur Russell, himself a noted composer. “Come on … come on,” says the play’s last speaker, as his words, in the printed text, gives way to a dash, then an ellipsis, then a stage direction calling for “silence.”52 As in the last act of A Thought in Three Parts, its protagonist “waiting” in a prolonged “now,” the urgency of Cascando’s own desire, and the hope with which its characters sustain it, assures us it will never be satisfied.

It’s tempting, in this context, to read Mabou Mines’s other two 1976 productions – a single February-afternoon presentation of The Saint and the Football Players and, in April, a revival of The Red Horse Animation (1970), the company’s first original work – as attempts to rebut Beckettian circularity with muscular defiance (in the former case) or disciplined attention to progressive motion (in the latter). As its title suggests, The Saint and the Football Players exalted sports even as it looked wryly at its rituals, deflated its hubris, and teased its acolytes. Scores of participants – playing team-members, referees, coaches, forklift operators, and a marching band – performed fragments of a game under the glare of car headlights in the Pratt Institute’s vast indoor gymnasium. The players called out signals (scored by Glass); vigorously executed passes and tackles; re-ran them in slow motion; regrouped and faced off again with a zeal heightened by the absence of scorekeepers, or even endzones. “No beginning, no culmination, no goal,” wrote Arthur Sainer, appreciatively, in the Village Voice. “Simply the floating perpetuation of movement … America as process.”53

In this, Mabou Mines was developing ideas it had first explored in The Red Horse Animation, a work inspired by Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs of animal locomotion. Yet the three actors who embodied horse and rider didn’t simply bring the images to life. That suggests an ease that Lee Breuer, who wrote and directed the piece, and whose obsessive attention to his artistic direction informed its action, withheld. Rather than simply anatomize motion (as Muybridge did), Breuer set it alongside the kinetics of thought and feeling. The production’s tripartite horse and rider worked to resolve the conflict between galloping invention and shying self-consciousness; to manage filial obligations even as it shook off other restraints; to focus on the evolving work of art without blinding itself to the longer route of a fulfilling life. In stop-and-start language that may have struck viewers in 1976 as especially resonant, the Red Horse protagonist finds himself at one point able to see clearly only the present moment. “I think this is the middle. … What now. What am I. Can’t tell much. I think I’m traveling. … I go through my changes. Forwards. And backwards. Sooner. Or later. I’ll come to where I am. I think. I’ll come to myself.”54 The as yet unachievable enjambment of his phrases, like the miraculous coordination of limbs that fascinated Muybridge, stood, for Breuer, as the longed-for freedom of instinct and imagination, and more generally, a newly purposeful progress through a once meandering, obstacle-filled life. (Whatever release the red horse enjoyed was finite. During a May performance, Warrilow injured his leg and could no longer perform; the company decided to end the run and retire the piece from its repertory.)55

The end of invention loomed large in two final works in this survey of 1976 experimentalism. It’s fitting we join their makers – the performance artist Scott Burton and the dance company Grand Union – as they created on the verge of oblivion, at a moment when they embraced rather than merely conceded their art’s ephemerality. The single-minded artist and the shifting collective took to opposite extremes the compositional principles they shared with their peers. They also tested them. One practice was purified of all superfluities; the other considered no amount of superfluity too great. Burton presented Pair Behavior Tableaux, a wordless piece for two men, over six weeks from February to April 1976 (Figure I.4). That it ran longer than most other vanguard works from this year, yet until recently had all but faded from theater history, emphasizes its ironies. It turned on the contradiction in its title – aiming to arrest in tableaux something as fluid as behavior. Its appearance at the Guggenheim Museum, a space dedicated to cultural preservation, suggested how futile it was to insulate any image, not just those created by Burton, from time. (Several of Burton’s other “behavior tableaux” – seven in all, from 1972 to 1980, for larger groups or individuals – also appeared in museums, art schools and institutes, or international exhibitions. He turned exclusively to sculpture in the decade before his death in 1989.)

Figure I.4 Scott Burton: Pair Behavior Tableaux, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1976.

If behavior is only legible as it changes, can it ever be codified? Many critics of the behavior tableaux argued it could be – that Burton was compiling a lexicon of gestures, signals, and semaphores, many corresponding to psychologically charged narratives of invitation or rejection, or power and subjugation, and of others more narrowly drawn from the manners of queer courtship and kinship, or, just as often, queer solitude. (David Getsy, in Queer Behavior, is the most nuanced of these scholars.)56 Yet one might equally argue that the performance’s ascetism and severe discipline – the lengths to which Burton went to eliminate markers of identity (except for gender and race) and clarifying contexts for the action, and to sand down the surfaces that remain – prevented such stories, even the most general, from ever emerging. The pieces enforced our distance from explicit meaning – literally so: Burton positioned audiences fifty to eighty feet from the stage, forestalling the uncritical habits of identification permitted at more intimate works. The figures themselves were impervious to appeal. They were roughly the same young age and same lean body type; moved at the same deliberate pace across the same shallow, largely empty stage; dressed identically in a simple uniform of pants and t-shirts; wore light make-up that covered their eyebrows (one critic said they looked like bank robbers with nylons pulled over their head); and stood on raised shoes that Burton, tellingly, called cothurni, in homage to the Greek tragedians whose own masked, distant, and presentational acting style formalized and externalized feeling.57

Yet tragedy’s declarative force was muted here, and not only because the actors never spoke. Burton rejected the qualities of psychologically explicit drama – character depth, fulfilled narrative, legible expression – in favor of a subtler charting of affect, one in which vagueness expanded a work’s reach and ephemerality left an enveloping, penetrating aftereffect. His materials were “attitudes rather than emotions,” he said.58 If spectators still insisted on seeking the latter in the actors’ behavior, Burton taught them to look in ordinarily unresponsive places: “I want people to become aware of … the emotional nature of the number of inches between them.”59 This combination of geometric specificity with affective ambiguity was strategic – attuned to mid-1970s social pressures and covert possibilities despite the works’ immaculate appearance. Queer conduct that, outside the theater, was under surveillance was here veiled in anonymity; avowals that might have been risky were unemphatic; attributes that could have marked the bearer indelibly, at least to an aggressively diagnostic eye, here remained provisional, inconclusive, unsticky, even (if need be) deniable. In the only surviving footage of Pair Behavior Tableaux, a man walks with agonizing slowness toward his seemingly unresponsive partner: Each step has the quality of a decision, one emphasized by his long legs, his shoes landing heavily if soundlessly, and the swinging flare of his bell-bottoms.60 (He recalls an astronaut walking on the moon.) His protracted advance suggests many potential transactions – sexual, of course, or simply domestic, or unnervingly confrontational, or even blandly commercial. The scene aches toward clarity, in time with the actor’s advance through the thick, viscous silence … until it finally plunges, unrealized, into the blackout. The darkened stage becomes a screen for our unanswered, now unanswerable questions. Or for proliferating answers: Burton is careful to imply that coded or tacit language, for those fluent in it, can be a source of pleasure as much as a protection against vulnerability. Its satisfactions derive from the arousal of meanings tantalizingly never confirmed.

In both its restraint and its openness, Pair Behavior Tableaux teaches lessons in how to watch other formally innovative works of the era. In their theaters as in this one, we learn to maintain our distance and cultivate our discretion; to refrain from imposing fixed or tendentious narratives upon patterned images, even as we keep many possible meanings in play; to see, rather than see through, a work’s apparent transparency; to pause over, rather than pass over, its empty spaces; and to relinquish what we look at soon after its appearance, aware that these images shine most brightly as they sink from view.

The disappearance of an entire company in 1976 showed what happens when one commits fully to these aesthetic priorities. Artists dedicated to moving eventually move on. Performance that edges close to failure – that requires of its performers continuous invention – is fated to one day fall. At the final New York engagement of the improvisatory dance company Grand Union, in April 1976, a dancer, Nancy Lewis, in fact did fall, and the fact that we couldn’t tell if the accident had been deliberate (it had a suddenness and heaviness that is startling even on videotape) suggests that the stakes of other kinetically committed work had never been clear until now.61 Grand Union emerged in late 1970 from Yvonne Rainer’s Continuous Project – Altered Daily, a large-scaled, densely populated work whose title suggests the ambitions and procedures of the new company as well. (Disco, which took over nightlife in this same decade, created other spaces for perpetual motion: a continuous project altered nightly.) Originally consisting of Rainer, Trisha Brown, Barbara Dilley, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon, Nancy Lewis, and Steve Paxton, the collective combined monologues, conversations, laments, and rants; obscure assemblages of everyday objects that they built and dismantled onstage; mock-tragic, obscurely suspenseful, and, most often, comedic skits; pedestrian movement and intricate dances that unfolded in silence, or alongside non-descriptive speech, or to the accompaniment of LPs chosen and played, in media res, by the dancers themselves. Everything was improvised. As the dancers traveled circuits of invention, they imperceptibly tuned in to one another, silently agreeing to prolong a sequence, pivot in a new direction, or abandon it abruptly … or to make apparent their disagreement, and see what interesting action might come of it. A performance’s rewards came less from any single moment (or phrase, or image) than from the current that carried the dancers there, and that would propel them on to the next one. As Deborah Jowitt emphatically put it in a review of the 1976 run, “what I appreciate most … is being able to see the processes that either instigate change or block it. … It means a great deal to me to watch performers making up their minds.”62

At the final New York performances, the group openly confronted those blockages, the wages of chronic change, and the desire for still more definitive, thoroughly transformational reinvention. As they did so, it was possible to imagine Grand Union acknowledging its imminent disunion. “I wasn’t trying to keep up with you until I couldn’t keep up with you,” said David Gordon as he hesitantly worked variations on Barbara Dilley’s movements in one episode. “I made her my leader and then I couldn’t keep up with my leader.” Later, happily separated from other performers, he stood on a folding chair (an object associated with him ever since his famous Chair dance in 1974), turned in slow circles as he relished the spotlight, and asked the audience “How long will you let this go on?” Longer than expected, but there were always other performers to look at in other corners of the La MaMa stage, denying Gordon the undivided attention he may have hoped for. Even partial attention eventually proved a torment: “Let me go,” he cried, finally. Continuous movement without a destination, once so desirable, could no longer guarantee the same rewards. Circularity was bringing diminishing returns, or sharpened frustration and claustrophobia. Duration, having overturned linear progression, now began to dull the very senses it meant to sharpen. “It goes on and on and … doesn’t ever seem to quite get finished,” said an increasingly desperate Valda Setterfield of her many daily routines – parenting, housework, keeping up with life in general. “Movies go on and on, and it’s the same movie. … I’m reading about four books … and I never get through them.” The relief of a climax, or the replenished energy that comes only with a radical break, will have to wait. Or will require a more aggressive intervention. “Doug and I are going off together,” said Gordon at the end of a later sequence, a trio with Dunn and Setterfield (Gordon’s wife), before the two men invited her to join them in a newly configured intimacy. Moments afterward, an even fuller narrative surfaced into the work, as Dilley read aloud from a piece of prose (another obscure family drama) while, all around her, the others piled up miscellaneous furniture and props, as if archiving or preparing to warehouse their history. Dilley stopped reading, took her shoes off, and put her feet up on a trunk: the dancing – and with it the company’s own story – was over.

*

It’s hardly accidental that several texts recited in Grand Union’s final New York run were about the domestic and familial: The security of those categories had grown compromised by 1976, for the Union members and for their loyal spectators. Not because (as Sennett, Hardwick, and Lasch would have it) the public sphere was beckoning ever more emphatically, urging all performers and audiences to look beyond affect and behavior, demanding they engage with something more than artistic procedures. Few 1970s experimentalists had entirely sequestered themselves from social pressures. None would have forgotten how earlier politically eventful eras had more urgently petitioned them. Yet some of the most unsettling work of the year – performances, writings, and other interventions – reengaged the familiar argument about art’s autonomy with a broader, more allusive and flexible idea of context than had shaped debate about social engagement a decade earlier. These artists’ vision of their proper relationship to their audience, and of how the contours of the artwork fit the space of its reception, was purposely open and plural – charged with all they didn’t know about what might happen when their work left the security of the rehearsal room or studio. The most analytic of them fastidiously attended to art’s borders, zeroing in on the moment when they (and, by implication, their audiences) had to choose whether or not, and how, to acknowledge the wider world. They positioned themselves between the temptations of immaculate formalism and the no less tempting messiness of social immersion: We witness their effort to negotiate between them. For these artists, the appeal of neutrality and “opacity” – the latter valued ever since Douglas Crimp identified it as the signature of advanced new art in 1973 – vied with their distrust of “mystification” and “the politics of no ideas” – words and phrases mocked in the Anti-Catalog (1977), a compilation documenting a broad-based artists’ protest against the Whitney Museum’s Bicentennial exhibition, “Three Centuries of American Art,” its contents drawn entirely from the private collection of John D. Rockefeller III. (The show included only one female and no Black artists.) “If you think art is ‘neutral,’ you’re kidding yourself – and ignoring history,” said one 1976 flyer publicizing the Artists Meeting for Cultural Change, the collective behind the protest.63

Of course not every publicly attuned artist felt required to take a forceful stand or make a declarative statement to engage the world surrounding their work. Others, while rarely ideological, took pains to situate themselves, and their art, in settings that their minimalist peers might consider unconducive to contemplative seeing. The distractions, for them, were welcome. Their objects and performances were abraded by the body politic – saturated by its currents, buffeted by its winds. Once an artist or company loosed a piece into the public sphere, it transformed unpredictably – the result of a combustible mix of composed and decomposing elements, of scripted and soluble qualities vying for precedence. Artists, on emerging from the studio or rehearsal room, could have tried to control their work’s presentation as forcefully as they did its creation. The more adventurous of them surrendered, happily, to the stronger, potentially disordering forces circulating in the theater or gallery. Or in even less contained viewing spaces: In November 1976, Cindy Sherman, in one of her earliest shows, exhibited her Cover Girls series inside an active Buffalo commuter bus – and perhaps welcomed how its motion jostled the dead-eyed magazine models she depicted.64

In this climate, it seemed only natural that the Whitney Museum mounted, in February, 1976, one of the earliest museum shows of live art – Performances: Four Evenings, Four Days, with works by Wilson, Foreman, Laurie Anderson, and others – and allowed the art form’s contaminants and shifting tectonics to send tremors through its once insulated galleries. Later that year, a group of artists and critics that included Sol LeWitt, Pat Steir, Walter Robinson, and Lucy Lippard founded Printed Matter, an organization to distribute artists’ books and other publications: Its first catalogue announced the era’s priorities with the slogan, “Art That Moves Out.” (After moving out, some of that art moved back in – to Franklin Furnace, a museum of artists’ books that had opened in April 1976.) Some of the same personnel were involved in Art-Rite, a mid-1970s newsprint magazine committed to tracing the “circuits” that “good art … creates.”65 To read it is to surrender to the syncopated rhythm of its layout, one in which no one picture or statement dominates. These were pages to be scanned, not contemplated – a paratactic idiom pioneered earlier in the 1970s by Newspaper, a magazine consisting entirely of photographs without captions. One Art-Rite issue from 1976 ran photographs of the facades of galleries and shops, as if they comprised the visual diary of a Soho flaneur. Another printed snapshots of crowds on escalators and subway stairwells. A third, drawing its contents “from the ambient culture” for “the average American in search of excitement,” alternated images of racing horses with tabloid-style pictures of crime scenes and celebrities.66

Live performance, unavoidably embedded in social life, of course had little trouble matching this openness to the city’s impurities, media cacophony, and hectic tempo. In one theater and spilling out from it that spring and fall, Jeff Weiss presented the latest in a proliferating series of exuberant, centrifugal plays. The two-part Two Dykkes (the misspelling indicative of Weiss’s more-is-more aesthetic) followed the title couple as they left their husbands in South Bend and took their song-and-dance act on the road (and eventually ran for president). The queer love story, propelled by irrepressible actors, unraveled norms; the earnestly performed Tin Pan Alley songs reknit them, while insisting that the lyrics accommodate transgressive desire. No less refreshing was how Weiss accommodated the occasionally treacherous accidents of urban citizenship. As with his every production at his tiny East 10th Street storefront, a room big enough for just seventeen spectators, the adjacent sidewalk was a pre-show party that Weiss hosted with aplomb, passing platters of watermelon, homemade raisin bread, and wine and cheese, and singing impromptu choruses by way of greeting the crowd. Inside the theater, with the street sometimes still visible through the window, he acknowledged latecomers and lost interlopers just as brightly, with applause and still more songs. The Soho Weekly News reviewer described Weiss’s art as a “theatre of flux [and] simultaneity,” and purposely contrasted it to the austere, searching work of Joseph Chaikin and Jerzy Grotowski, avatars of 60s experimentation.67 Weiss, for his part, saw his “nervous breakdown” theater as a rebuke to the “slow-motion” “fascism” of Wilson and Foreman.68 What, on another stage, would derail or stop a show, here was fuel for fresh invention.

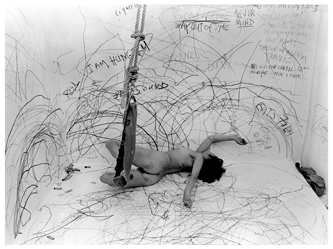

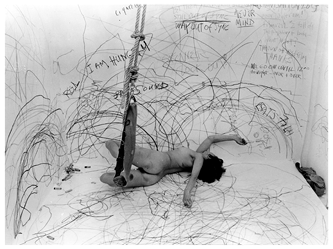

Weiss putting a latecomer on the spot could make everyone in the audience aware of the discipline and contours of their own attention, as could the glimpses of curious passersby on the sidewalk. Looking – an act that may have seemed neutral, and whose subjects typically enjoy anonymity – now acquired, in an unlikely setting, higher stakes. Carolee Schneemann’s own embrace of flux interrupted the seductions of the image even more defiantly. As early as 1962, Schneemann had been referring to her work as “kinetic theater.”69 By 1976, the ethical challenge and political demand launched by that motion were especially hard to evade. “You DID NOT ACTUALLY SEE Up to and Including Her Limits,” she wrote to a friend, the poet Clayton Eshleman, after he suggested that the power of this solo performance was erotic. “I do not ‘show’ my naked body! I AM BEING MY BODY.”70 For this work, Schneemann hung suspended from the ceiling in a sling, nude, dangling above and drawing on large sheets of paper taped to the walls and floor (Figure I.5). Most of her marks were abstract, but sentences sometimes emerged from the thicket of clashing lines. “I am Hungry,” she wrote in a Berlin performance that June, recalling us to the human source of mechanical processes. “We go on until 12:00 tonight – over + over” – a reminder that her piece spreads across and thrives in time. “Look Out” – a challenge to assumptions about who has the most power in a work that puts its maker in a truss. She was at once gravity’s victim, collaborator, and fierce protester, outwitting those spectators who might try to immobilize her with their objectifying attention. As Amelia Jones writes about Schneemann’s work in general, the artist “recognizes that it is in part the movement of the sexualized body in performance that is so threatening to interpretative systems.”71 Perhaps to no system more than Erving Goffman’s. The sociologist, examining performance stills that Schneemann had described at a late 1970s conference, argued that “a woman in a harness hanging from a rope is an object of sadomasochistic fetishism.” Schneemann countered that she was “flying and floating free.”72 She had elsewhere noted that she herself controls the rope – “I can raise or lower manually to sustain an entranced period of drawing” – and that she retains her will throughout: “My entire body becomes the agency of visual traces, vestige of the body’s energy in motion.”73 It quickly became apparent that Goffman could sustain his claim only by favoring the still photograph over the live, ungraspable performance.

Figure I.5 Carolee Schneemann: Up to and Including Her Limits, Studiogalerie, Berlin, 1976.

One final provocation would have awaited audiences at certain performances. Schneemann’s beloved cat Kitch, a presence in several of her films and other works, died on February 3, 1976. Ten days later, the New York engagement of Up to and Including Her Limits opened at the Kitchen, an important center for experimental music, video, and performance. Schneemann chose to include Kitch’s corpse as part of the installation: The cat lay on a table just downstage from the pages Schneemann drew on – offstage, but nonetheless an inexorable draw on spectators’ attention. It forced us to “look out,” beyond the implied frame. The distraction introduced an argument – one about the responsibilities we incur on choosing to attend to, and thus frame, anyone’s experience, or more precisely, about the opportunities we sacrifice when we set conservative limits on how much life (or death) we will acknowledge. The corpse drew us away from the scene proper – it unsteadied those of us who might have preferred to think about Schneemann’s work only in formal terms, as mere movement and marks – just as the performance’s other body, Schneemann’s exceedingly alive and startlingly present one, pulled us off the drawing’s surface. Schneemann’s notes for a Berkeley museum performance of Up to and Including Her Limits enlarged upon this theme by expanding the frame even more. She had planned to display on the gallery walls documents about “getting here” and “being here.”74 Letters from producers about her budget, notes to her partner still at home, bills to be paid, maps of the host city, lists of phone numbers and appointments, reminders to find a health food store, and so on: They all quietly insisted (as Weiss, in his own idiom, did) that the liveness of this performance cannot be contained by the stage, nor even by the artist displaying herself on it. This is one meaning of the word “including” in the title. The art, whose demands shape the life of its maker, itself has a life, one measured in subtotals, contact numbers, coordinates, and itemized tasks. (Materialist analysis was in the air in 1976: The final issue of the influential art journal Avalanche, out that summer, printed a page from its bookkeeping ledger on its cover.) To look at Up to and Including Her Limits fully, properly, one must look back to the work of conceiving and developing it, and then outward, as the aperture dilates, to the effort of sustaining and disseminating it … work that indeed must “go on … over + over.”

*

That work goes on, but the work – the show – does not. The Kitchen presentation of Up to and Including Her Limits (which had been appearing in earlier versions since 1973) lasted only two nights. In the brevity of its run, it was typical of other works now recognized as enduring landmarks of the avant-garde. The original American staging of Einstein on the Beach also ran for just two performances in 1976. A Movie Star Has to Star in Black and White appeared eight times in a not-for-review workshop. Rumstick Road had one public presentation in December before retreating from view until the following spring. A Rat’s Mass / Procession in Shout had a creditable eleven-show run, but it was so overlooked or disparaged by the press that it dropped from history right after its appearance. (Taylor’s score was never recorded.) Quarry had a slightly longer run – fifteen performances before a year’s-end return engagement. Some of these works toured or were revived in later years, and many have been preserved on video, but a few are lost forever. (With the deaths of Spalding Gray and Ron Vawter, Rumstick Road will likely never reappear in live form, despite the Wooster Group’s commitment to regularly revisiting and rethinking its archive.) For the many who missed these works, they became the stuff of rumor and legend.75 Given such merciless transience, the more durable arrangements formed among the artists themselves took on outsized importance: They compensated for a culture of loss. These emblems or narratives of kinship were also, in some cases, legible in the performances. To look at them is, following Schneemann’s graffito, also to “look out” at the encounters, pledges of affection, histories of collaboration, and traces of looser, less formal bonds that shaped the artists’ day-to-day lives in New York.