Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword: Hate Speech and the Coming Death of the International Standard before It Was Born (Complaints of a Watchdog)

- Foreword: Hate Speech and Common Sense

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Overviews

- Part II Refinements and Distinctions

- Part III Equality and Fear

- Part IV International Law

- 22 Does International Law Provide for Consistent Rules on Hate Speech?

- 23 State-Sanctioned Incitement to Genocide

- 24 A Survey and Critical Analysis of Council of Europe Strategies for Countering “Hate Speech”

- 25 The American Convention on Human Rights

- 26 Orbiting Hate? Satellite Transponders and Free Expression

- Index

- References

26 - Orbiting Hate? Satellite Transponders and Free Expression

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword: Hate Speech and the Coming Death of the International Standard before It Was Born (Complaints of a Watchdog)

- Foreword: Hate Speech and Common Sense

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Overviews

- Part II Refinements and Distinctions

- Part III Equality and Fear

- Part IV International Law

- 22 Does International Law Provide for Consistent Rules on Hate Speech?

- 23 State-Sanctioned Incitement to Genocide

- 24 A Survey and Critical Analysis of Council of Europe Strategies for Countering “Hate Speech”

- 25 The American Convention on Human Rights

- 26 Orbiting Hate? Satellite Transponders and Free Expression

- Index

- References

Summary

Introduction

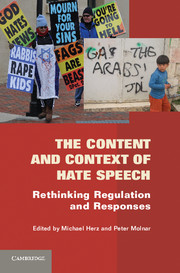

In this chapter, I deal with the consequences of two significant changes: an expansion – a rather substantial one – in the categorization of various kinds of expression under the loose rubric of “hate speech” and simultaneously the increasing use of satellites to hurl this speech around the world. I examine a series of case studies dealing with programming transmitted by satellite that is connected to division and conflict – in these cases, conflict mostly related to societies in the Middle East.

One might anticipate that regulatory crises occur when organized and often status quo-disruptive senders shape a persistent and effective set of messages to be transmitted within a society and/or across national boundaries as part of an overall effort to gain substantial influence on target populations. As the case studies will show, when such messages have been transmitted by satellites, they have produced decisions by governments and powerful groups that have been almost invisible and exist outside a clear legal framework of articulated norms and transparent processes. One feature is paramount: Formal regulation of the content of satellite transmissions, including of speech with alleged attributes of hate, with few exceptions, rarely has been an effective theater for playing out governmental interests in satellite signal diffusion. There is also a lack of scholarly literature on the ways in which governments seek to control or affect the functioning of satellite services and their transnational distributions. In a sense, this underscores a major point: Decisions to allow or prohibit distribution of satellite signals have been treated more as strategic business decisions than as an interplay between national interests and free-expression values. Having these decisions take the form of leasing and subleasing of transponders, they become mere economic transactions, underplaying their role as modes of intervening in national public spheres. In addition, because there is a relative absence of judicial decisions or similar official documents, observers must rely largely on reportorial and journalistic accounts and on information gleaned from Web sites and other unofficial sources.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Content and Context of Hate SpeechRethinking Regulation and Responses, pp. 514 - 538Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2012

References

Accessibility standard: Unknown

Why this information is here

This section outlines the accessibility features of this content - including support for screen readers, full keyboard navigation and high-contrast display options. This may not be relevant for you.Accessibility Information

- 2

- Cited by