-

Select format

-

- Publisher:

- Cambridge University Press

- Publication date:

- 03 November 2016

- 20 October 2016

- ISBN:

- 9781316480625

- 9781107137295

- 9781316502570

- Dimensions:

- (234 x 156 mm)

- Weight & Pages:

- 0.78kg, 387 Pages

- Dimensions:

- (234 x 156 mm)

- Weight & Pages:

- 0.66kg, 390 Pages

You may already have access via personal or institutional login

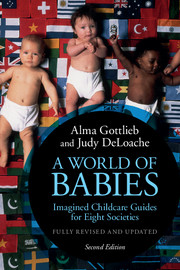

Book description

Should babies sleep alone in cribs, or in bed with parents? Is talking to babies useful, or a waste of time? A World of Babies provides different answers to these and countless other childrearing questions, precisely because diverse communities around the world hold drastically different beliefs about parenting. While celebrating that diversity, the book also explores the challenges that poverty, globalization and violence pose for parents. Fully updated for the twenty-first century, this edition features a new introduction and eight new or revised case studies that directly address contemporary parenting challenges, from China and Peru to Israel and the West Bank. Written as imagined advice manuals to parents, the creative format of this book brings alive a rich body of knowledge that highlights many models of baby-rearing - each shaped by deeply held values and widely varying cultural contexts. Parenthood may never again seem a matter of 'common sense'.

Reviews

'Gottlieb and DeLoache’s first edition of A World of Babies earned the right to be called a classic of anthropology. Although one might expect the second volume … to be a simple update of the same studies, Gottlieb and DeLoache have instead done the unexpected - they present an entirely new volume with seven new studies of parenting practices. Taken together, these books set the example of how anthropology, when done well, can open minds to the possibility that there is more than one way to do just about anything, including parenting. I can think of no better way to become a more thoughtful, insightful, and therefore better parent than reading both editions of A World of Babies.'

Meredith F. Small - Cornell University, and author of Our Babies, Ourselves

'I cannot effuse enough about the second, fully revised edition of A World of Babies! The first edition has been a mainstay in my classroom for over a decade, and I have frequently given it as a gift to new parents. The creative, innovative, quasi-fictional design of both editions - ’imagined childcare guides’ authored by ethnographers studying in a broad range of cultures, writing as if they are imparting knowledge to new parents as a childcare expert, such as a grandmother, midwife, or diviner - makes A World of Babies an enjoyable and impactful read for students and new parents alike. At a time when it may seem like there is no ‘right’ way to raise a child … it is refreshing to read a book which concludes that, in fact, there are many ‘right’ ways to raise children.'

Christa Craven - College of Wooster, and author of Pushing for Midwives: Homebirth Mothers and the Reproductive Rights Movement

'This is a fantastic book! I am going to use it right away with both my large undergraduate class and advanced graduate seminar … It [has] an impressive array of authors, each with deep knowledge of the culture for which they are preparing their ‘advice'.'

Patricia Greenfield - University of California, Los Angeles, and author of Mind and Media: The Effects of Television, Video Games, and Computers

'A World of Babies provides terrific and vivid personal examples reminding us of the importance of family, culture, history and context in children’s lives in today’s globalizing world.'

Thomas S. Weisner - University of California, Los Angeles, and co-author of Higher Ground: New Hope for the Working Poor and Their Children

'This very accessible yet soundly scholarly book reads like a novel describing the same event from different perspectives, thereby shedding light on the socio-culturally constructed nature of what we might think of as ‘objective’ and self-evident ‘truths’ about early child development. A ‘must-read’ for students and researchers in the area of developmental psychology as well as a great read for anyone interested in the world of babies.'

Alexandra M. Freund - University of Zurich, and co-editor of The Handbook of Life-Span Development: Social and Emotional Development

'Starting with a most captivating and comprehensive overview of the worldwide challenges facing twenty-first-century parenting, alongside their seven, fictitious, ‘composite person’ community authors, who could (if real persons) appropriately dispense ‘how to’ infant care advice, yet again, Professors Gottlieb and DeLoache manage to spin their baby-care magic for both students and professionals alike … the seven new (and one updated) chapters provide, as did the first edition, a sparkling set of ‘manuals’ but with an even greater degree of wit, clarity, and intimate cultural knowledge, spreading cross-cultural insights that at times shock, amuse, and entertain, but always shed further light on the diverse … ways both biology and culture find expression in how we care for our babies.'

James J. McKenna - University of Notre Dame, and author of Sleeping with Your Baby

'[A] clever, refreshing, indeed witty way to engage readers … not only in the study of children, childhoods and socialization, but also in the conduct of ethnographic field research and the ways in which we present our work.'

Myra Bluebond-Langner - University College London, and author of The Private Worlds of Dying Children

'The editors, in the second edition of A World of Babies, have made a great book out of a very good one. The work is unique in combining perspectives not normally found in a single case study … we learn much about the enormous diversity in cultural practices vis-à-vis babies and about the contemporary forces that provoke change and resistance to change.'

David F. Lancy - Utah State University, and author of The Anthropology of Childhood

'This lively, well-written book is authoritative, but not in the usual way. It's not going to tell you how to give birth or raise your child. Instead, it will tell you many ways to do it, each blending a deep cultural tradition with the modern world. It's the perfect antidote to the worst parenting myth: 'there is one right way, and if I don't find it my child will suffer'. Treat yourself instead to A World of Babies, and encounter a wide world of ways.'

Melvin Konner - Emory University, and author of The Evolution of Childhood

'They had me at page 1: encountering a few of the differences in beliefs held around the world about raising babies made me eagerly read for more. Students of child development at all levels of education need this book to help them gain perspective on their own culture’s child-rearing practices. Practices that appear ‘natural’ and unquestionable are in fact deeply rooted in physical, cultural and economic realities … The book is brilliant. I can see this book generating extensive discussion and provoking endless consideration of the role of nature and nurture in child development.'

Roberta Michnick Golinkoff - University of Delaware, and author of How Babies Talk

'This thoughtful and engaging book should be read not only by anthropologists and psychologists but by all expectant mothers. It makes American child-rearing seem distinctly exotic. At the same time, it shows how much all mothers share. The effect is both liberating and moving.'

Tanya Luhrmann - Stanford University, and author of When God Talks Back

Review of previous edition:'If you ever find yourself assuming that there's just one right way - your way - to bring up babies, read this book. It's highly enjoyable and such a good idea that I only wish I'd thought of it myself.'

Penelope Leach - author of Your Baby and Child, From Birth to Age Five

Review of previous edition:'Every American parent should reflect on these cultural essays.'

Jerome Kagan - Harvard University, and author of The Nature of the Child

Review of previous edition:'Having a baby is a life-enhancing and mind-extending trip into new lands, much like the marvelous anthropology of child-rearing in this book. Take its expedition and it may help clarify the values and contexts of your own parenting, and bring the world's children into the clearer focus of our knowledge and concern.'

Catherine Lutz - Brown University, and author of Schooled: Ordinary, Extraordinary Teaching in an Age of Change

Review of previous edition:'Read these pages. This is a very moving book, and a revealing one.'

Jerome Bruner - New York University, and author of Child's Talk

Contents

Citations and Sources Cited

1 Raising a World of Babies

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to the numbered references in the Sources Cited section immediately following for this chapter. Page

- 3

skyrocketing US interest in “other” childrearing strategies – 86; TED talk – 16; China-inspired parenting book – 17; France-inspired parenting book – 22, 89, 95; willingness to “parent in public” – 74; books about comparative parenting styles – 31, 46

- 4

what people accept as “common sense” in one society is often considered odd, exotic, or even barbaric in another – 25; on Benjamin Spock as “the world’s most famous baby doctor” – 48; Dr. Spock’s book has sold over 50 million copies – 85; similar childrearing challenges for all parents – 52

- 5

infant mortality rates by country – 90; effects of European colonialism on populations of the global south – 27

- 6

3.1 million children die from hunger each year – 101; the world’s farmers produce enough food to feed the world’s population – 65

- 7

wet nurses in the ancient world, and elite families in western Europe from the eleventh to the eighteenth century – 23; wet nursing: in Paris of 1780 – 42, in Europe until World War I – 23; “milk kin” – 19, 43; cow’s milk and death in Iceland – 33; recommended length of breastfeeding: by the American Academy of Pediatrics – 3, by the World Health Organization – 98

- 8

rates of breastfeeding: in US – 13; globally – 98; population lacking access to safe water – 100; diluting infant formula from poverty – 75

- 9

lawsuits against employers and restaurants in the US to support public breastfeeding – 38, 54, 102; call for a return of “wet nurses” to help working mothers – 68

- 11

older children take care of babies: effective in “traditional” societies – 93

- 11–12

impossible in contexts of extreme poverty – 20; dangerous in the favelas of northeastern Brazil – 75

- 12

adoption on Ifaluk – 49; international adoptions within communities spanning national borders – 18; interracial and international adoptions: increasingly popular – 76, sometimes becoming human trafficking schemes – 15

- 13

emotional ties of young children: with older siblings – 93, with daycare teachers – 37; infants’ ties to ancestors: via reincarnation – 27, among Baganda 44, among Warlpiri – 66; Portuguese concept of saudade – 29; recent comparative work by developmental psychologists: on children’s lives – 77, on “attachment theory” – 64, 72

- 14

young children learn as apprentices: weaving – 70, washing laundry, cooking, weeding, hoeing, and harvesting – 97, doing errands – 61

- 16

- 17

co-sleeping: in modern societies – 78; co-sleeping: in Mayan families – 60, in Japanese families – 1, 12; babies sleep solo: rare cross-culturally – 79, recommended by American pediatricians – 53, recommended by public health campaigns in Milwaukee – 58, recommended by public health campaigns in New York City – 63, 92; co-sleeping among Asian versus White parents in the US – 62; “attachment theory” mischaracterized in popular discussions – 91; co-sleeping stigmatized and under-reported in the US – 55; co-sleeping: claimed to increase the risk of SIDS – 4, claimed to reduce the risk of SIDS – 55

- 19

infants sleeping solo seen as shocking mistreatment by Mayan mothers – 60, and by others elsewhere – 78; “cultural intimacy” – 35

- 20

effects of long-term political strife and poverty on parents and children – 21

- 21

relatives no longer available to advise many new mothers in US – 96; pediatricians and books as common sources of information about parenting in Western nations – 32

- 22

“Parenting Industrial Complex” – 69; eager readership of parenting books – 39; parenting books appeal to what readers already know – 57

- 23

- 24

article spoofing Spock – 26

- 25

societies with a long tradition of literacy having earlier parenting manuals – 5; contemporary Chinese mothers seek parenting advice online – 14

- 26

changing American ideas about blue and pink – 56

- 27

experimental writing among scholars – 2, 8, 11, 24, 28, 59, 67, 71, 82, 83, 84, 87; parenting manuals: in Renaissance Italy – 9, in China – 5, 79, in contemporary Western societies – 30, 94

- 28

dramatic changes in children’s lives globally: positive health indicators – 99, recruitment of child soldiers – 80

- 30

work by developmental psychologists acknowledging cultural differences – 10, 40; WEIRD research subjects – 34, 41; new cross-cultural studies of childhood by psychologists – 47; new interest in children by anthropologists – 6, 7, 73

Sources Cited – Chapter 1

2 Never Forget Where You’re From

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to the numbered references in the immediately following Sources Cited section for this chapter. Page

- 33

religious profile of Guinea-Bissau – 23, 26; population of Fula in Guinea-Bissau – 26

- 34

“if the cattle die . . .” – 15, p. 25; population of Mandinga in Guinea-Bissau – 26; description of Muslim versus indigenous societies in Guinea-Bissau – 5

- 35

migration from Guinea-Bissau to Portugal – 1, 6, 24; Guinean Muslims migrated from rural areas in Guinea-Bissau – 25

- 36

population of Muslims in Europe and in Portugal – 30; number of Guinean Muslims outnumber Indian Muslims from Mozambique – 31

- 37

Guineans in Lisbon are becoming critical of polygyny – 2

- 40

infant and maternal mortality rates in Guinea-Bissau and Portugal – 7; Allah fixes the time and place of death at birth – 20

- 41

how a belly is made, and contributions of male and female sexual fluids – 18

- 43

obtaining Portuguese citizenship for your baby – 14

- 44

hospital births rising in Guinea-Bissau – 16; a laboring woman may have a birthing companion in Portugal – 27

- 45

excision prepares a woman for childbirth pain – 17; true sweetness must entail suffering – 17; African women’s labors are easier, due to absence of chemicals in food, and to farm work – 21

- 46

- 50

rely on mobile phone to “visit” – 22

- 52

spirits move easily between Guinea-Bissau and Portugal – 29

- 54

magical practices for protecting White Portuguese babies from witches – 11; child fostering in Africa – 13

- 55

many Portuguese babies are weaned by 3–6 months – 10; children acquire personality traits and habits through breastfeeding – 28; breastmilk is a “kinship glue” – 32, p. 47; children of one mother are close and trusting, while children of one father are distant and competitive – 3; “milk kin” – 4, p. 100; 9, p. 136

- 56

avoiding pork is difficult in Portugal – 12; colostrum “thin and weak” and not fed to Mandinga babies – 32, p. 51

- 57

avoid sex until baby begins walking – 32; breastmilk during pregnancy belongs to fetus – 32; “Let go of the breast!” and threaten to put hot pepper on your nipples – 32, p. 56

- 58

the importance of three rituals (name-giving ritual, circumcision, writing-on-the-hand ritual) for Mandinga identity – 18

- 62–65

writing-on-the-hand ritual – 18

- 64

parents must keep channels of communication open between children and angels – 18; waking sleeping children disrupts communication with angels – 18; female nudity and keeping dogs in apartment scare away angels – 18

- 65

writing-on-the-hand ritual as magical safeguard against alcoholism – 18; “big initiation” and “little initiation” are changing – 17, 19

- 66

Kankuran protects initiates from witches – 8

- 67

today girls are circumcised earlier – 17, 19; when a girl’s clitoris is cut, God can hear her prayers – 17, 19; many Guinean Muslim men in Lisbon now oppose female circumcision – 19

- 68

female circumcision tames a girl’s sex drive – 17, 19; danger of circumcising a sexually active girl – 19

- 70

news travels fast by mobile phone in Guinean immigrant community in Lisbon – 19, 22

Sources Cited – Chapter 2

3 From Cultural Revolution to Childcare Revolution

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to the numbered references in the Sources Cited section immediately following for this chapter. Page

- 71

- 72

collectivization – 29; women’s roles and experience during Communism – 21; women in Communism and family violence during Communism – 21, 29

- 73

One Child Policy and modernity – 5; modernity and birth planning – 16, 17, 18; only children and family’s hope – 13

- 74

household registration system, legality, and social stratification – 26; family separation – 14, 15, 41, 42, 43; migration and Spring Festival – 8; government and “high quality” citizens – 1, 2, 3, 11, 16, 20, 27, 28, 32, 33, 34, 46

- 74–5

- 75

fosterage and adoption of abandoned, female, and disabled children – 7, 22, 23, 28, 30, 31, 34, 37

- 75–6

- 76

intergenerational relationships – 14, 15, 30; argumentative communication – 47

- 77–8

prevailing importance of intergenerational relations – 4, 6; children as parents’ hope for security – 13

- 81–2

local marriages under Communism – 29

- 83–5

intergenerational tension over prenatal vitamins – 47

- 84

Chinese personhood – 28

- 86

the changing value of girls in modern China – 12

- 86–7

increasing number of babies born with birth defects – 19

- 87

- 89–90

- 90

work as an idiom for love – 29

- 90–1

modern psychology of childrearing – 28

Sources Cited – Chapter 3

4 A Baby to Tie You to Place

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to the numbered referencing in the following Sources Cited section of this chapter. Page

- 94

expelled from their homes – 47, 59; al-Nakba, meaning “the catastrophe” – 24; longest military occupation – 34; increasingly criticized – 13; the second intifada – 56; illegal by the United Nations General Assembly – 68

- 95

Israelis and Palestinian injured or dead – 23, 41; separation wall – 22, 69; checkpoints – 70; the permit system – 3, 66; demolition of Palestinian homes – 6; violation of international humanitarian law – 27; Fourth Geneva Convention – 43; decrease in public support for “settlements” – 62; others who are more distantly related – 44; strong ties with the hamula – 35; members numbering in the thousands – 15

- 95–6

daily interaction and socialization – 31

- 96

relatives beyond those in the ‘a’ila – 44; strengthened family ties – 65; socialize within the confines of the hamula – 42; levels and structures of mobility – 36, 37; central to Arab culture and practice – 73; Israel citing security risks – 16, 63

- 97

since the 1948 Nakba – 2; internal deficiencies within the Palestinian Authority – 60

- 98

money to support the hamula – 2; weakening the economic situation in the West Bank and East Jerusalem – 67; pools its resources for family needs – 42; 161 Palestinian dead and another 700 injured – 53; Palestinian killed by other Palestinians – 21; targeted each other’s activists, leaders, and supporters – 18, 19, 53; accused of being “collaborators” – 20; death for being a “collaborator” – 14; human rights organizations have documented instances – 14; collaboration has been broadly defined – 20

- 99

collaboration includes acts that are deemed immoral – 20; marriage is often central to a family’s survival – 2; members of ‘a’ila consulted in decision-making process – 15; women tend to join their husband’s families – 15; Palestinian society is young – 25; responsibility often falls upon the oldest son – 42; “honor” is reflected in the “virtuous” behaviors of its women – 42; “honor” has expanded to include other elements – 42

- 100

maintenance of traditional values and customs – 42; women are considered to be some of the most educated women – 58

- 104

marriage governed by customary orthodox Sunni Islamic law – 30; legally seek divorce – 30; 4.5 percent of families in the West Bank practiced polygamy – 71; psychological and economic distress – 52; stressful for children – 9, 10

- 105

dayat – 46; discouraged home delivery births – 17; 3.2 percent of births in the West Bank – 54

- 106

eating dates during the last month of pregnancy – 11

- 107

“checkpoint” – 70; pregnant women stuck at checkpoints – 49; pregnant and laboring women were refused passage – 12; exposed to tear gas – 40

- 111

depression because of the political situation – 4, 7; breastfeed up to two years – 51

- 112

symbol of Palestinian resistance – 64

- 114

maternity leave – 55

- 116

food allergies – 33

- 117

Qabr Yūsuf – 57, 72; considered a holy place – 25, 56; site of intense conflict for centuries – 48, 57, 61; Israeli army prohibits Palestinian Muslims – 1, 28, 29, 38, 39

- 118

in the company of older siblings or cousins – 50; protect them from violence – 5, 7

- 119

resist the Israeli occupation and its violence – 8

Sources Cited – Chapter 4

5 Childrearing in the New Country

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to the numbered references in the Sources Cited section immediately following this chapter. Page

- 123

construction of shared peoplehood in contemporary Israel – 11

- 124

Zionist ideology – 5, pp. 3–13; factors facilitating the spread of Hebrew as lingua franca among Jewish settlers in Palestine – 41

- 125

Palestinian population of Israel – 1, 25; occupied territories and Jordan Palestinian population of – 6, p. 5; creation of Palestinian refugee problem – 40

- 126

complex relations between the Jewish majority and the Palestinian minority – 3, 46, 51, 54, 56; Israel a “deeply divided society” – 52

- 127–8

surveys of religiosity – 4

- 128

evolving meanings of terms, Sephardi and Mizrahi – 18; increase of Mizrahi Jews to 40 percent – 47; construction of overarching “Mizrahi” identity that disregards internal diversity – 19

- 129

development towns – 51, pp. 80–1; rise of Mizrahi middle-class in Israel – 10, 38; Israeli “melting pot” as success or failure – 61; Ethiopian immigration statistics – 47, p. 4

- 130

recent education and employment trends among Ethiopian Israelis – 58; newcomer groups in Israeli society including Russians, Ethiopians, and labor migrants – 31, pp. 130–72; 51, pp. 308–34; implications for educational policy of lack of recognizing diversity among Russian-speakers – 8; what is “Russian” about diverse population of Russian-speakers in Israel? – 34

- 130–1

comparison between Mizrahi immigrants of the 1950s and Russian immigrants of the 1990s – 53

- 131

occupational fates of various professional groups among immigrants from former Soviet Union 14, 35, 42, pp. 73–93, 53, 55; Russian immigrants’ social enclave and political mobilization – 42, pp. 138–42; adolescents’ adaptation – 12; Mizrahi Jews’ attitudes toward Russian immigrants – 42, pp. 153–6

- 132

familism – 16, p. vii; changes in family patterns over the past five decades and across socio-ethnic groups – 32; continuing centrality of familism in Israeli society – 15; family policy and public attitudes – 36; womanhood and motherhood in Israeli society at the interface of religion and nationalism – 7, 15, 31, pp. 175–9; ethnographic studies of Israeli-Jewish motherhood via assisted conception – 26, 27, 59; pregnancy – 26; among Palestinian Israeli women – 28; poverty indicators – 56

- 133

women in Israel are relatively well educated – 24

- 133–4

education in Israel – 51, pp. 294–6, 60

- 134

Israeli education system – 60; school matriculation statistics – 56; more optimistic account – 2; structural and demographic accounts of early education in Israel preceding recent changes – 30, 57

- 134–5

attitudes toward early education among newcomers from the former Soviet Union – 43, 45; preservation of the Russian language as factor in parents’ choice of early education settings – 39, 48; immigrants establish own education system – 23, 49

- 135

- 137

- 138

continuity and change among women of Moroccan descent in Israel – 17, 38

- 140–1

experience of pregnancy among Israeli women: and sense of threat – 26; and elaborate system of prenatal testing – 26, pp. 37–76; and quest for medical information among pregnant women – 26, pp. 204–16

- 141

pregnancy and birth rituals among Israeli women of various ethnic backgrounds – 50

- 147

teaching traumatic historical events to young children – 9, 62; differences in political talk between Jewish and Palestinian early education teachers – 22; school trips to Poland as pilgrimage – 13

- 148

tendency to depoliticize political issues through use of psychological discourse in early education – 21

- 150

education as means for upward mobility among Moroccan-Israeli women – 38

- 151

importance of peer group and key symbol of “crystallization” (gibush) – 29

Sources Cited – Chapter 5

6 Luring Your Child into this Life of Troubled Times

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to the numbered references in the Sources Cited section immediately following this chapter. Page

- 153–4

- 154

Ivorian groups who actively resisted colonization – 34; French colonial history of West Africa – 24; on Houphouët-Boigny’s reign – 18, 24; early warning signs of economic and political trouble – 6, 16

- 155

vigilante justice – 17; civil war – 23; early structural causes of the civil war – 22

- 156

on increasing poverty under colonial domination in Africa – 28; fragility of post-conflict rebuilding of infrastructure and democracy – 4, 31; toxic waste dumping in Abidjan by multinational corporations – 2; problematic youth behavior – 26; religious and ethnic xenophobia – 1, 3, 25; religious extremism – 19; human rights abuses – 33; negative implications of the declining economy and weak infrastructure for children’s lives – 29, 30

- 157

Beng regional and political structure – 8

- 158

extended families, clan structure, and arranged marriage rules – 10; rebellion against arranged marriage – 13, 14; indigenous Beng religion – 10, 13

- 159

- 160

religious and mundane not easily distinguished – 10

- 165

two worlds of people and animals remain connected – 10

- 170

Sources Cited – Chapter 6

7 From Mogadishu to Minneapolis

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to the numbered references in the Sources Cited section immediately following this chapter. Page

- 191

- 192

primary school – 9; girls in education – 9; women in teaching profession – 9; refugee statistics – 32

- 193

Dadaab refugee camp – 33; encampment policy – 19; Somali refugee-cum-suspects – 5

- 194

- 195

Islamophobia in Minnesota – 7; Halloween costume – 14; reasons for Minnesota as destination for Somali diaspora – 15; Somali businesses – 15, 29

- 196

dugsi – 28

- 197

communal – 22; social interconnectedness – 20; child obedience – 12

- 198

closing of coastal refugee camp – 8

- 202

- 203

infibulation – 21; complications of infibulation – 21; shame over gudniin – 34

- 204

Somali women misunderstood – 34

- 205

increased C-sections – 21

- 206

- 207

special foods – 25

- 208

wanqal – 1

- 209

abtiris – 1; the travels of Igal Shidad – 11; Qayb Libaax – 2

- 210

pumping breastmilk – 18; nursing in Islam – 31; challenges to exclusive breastfeeding – 27

- 211

- 212

- 215

statistics on autism in Somali community – 17

- 216

vaccinations – 35

- 220

- 221

North Carolina murders – 30

- 222

the Prophet and men’s house work – 3

Sources Cited – Chapter 7

8 Quechua or Spanish? Farm or School?

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to the numbered references in the Sources Cited section immediately following this chapter. Page

- 226

pre-colonial history and Spanish conquest of the Incan empire – 27, 42; Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala – 27, 42, 43, 47

- 227

José María Arguedas – 5, 6, 7, 42; Peru’s colonial history – 27, 42; history of Peru’s independence and early nationhood – 19, 20, 42; Peru’s first constitution – 11

- 228

numbers of dead and disappeared – 36; Andean communities’ attitudes toward/experiences with schooling – 2, 3, 4, 9, 20, 26, 28; history of Shining Path – 23, 36, 42, 44, 45

- 230

meaning of “respect” for Quechua speakers in the Andes – 12, 13, 18, 22, 26, 32, 40

- 231

importance of “respect” in Andean childrearing and social norms – 12, 13, 21, 22, 26, 32

- 233

- 238

- 239

- 240

Andean practices of “reciprocity” – 1, 12, 14, 26, 29, 33, 37, 43, 47; sacred nature of water, mountains, all forms of life and landscape in Andean cosmology – 1, 10, 12, 29

- 241

reciprocity and postwar reconciliation – 45

- 242

- 245

- 246

- 247

protective water – 13; synchronization of Catholicism with Andean cosmology – 1, 12, 13, 29; first haircut – 12, 13, 31

- 250

disciplining children – 13, 14, 22, 26, 39; children’s household labor – 13, 15, 26, 30

- 251

- 253

- 254

- 256

Andean children’s aptitude for math – 13

- 259

Sources Cited – Chapter 8

9 Equal Children Play Best

Citations

The numbers in the citations below refer to numbered references in the Sources Cited section that follows these citations. Page

- 261

- 261–2

relationship to Denmark –13; relationship to the European Union –16; closeness of family, valuing tradition – 13

- 262–3

traditional and modern subsistence, historical struggles – 13

- 262–4

importance of independence and family – 15, 16; changes with World War II – 49; technology and lifestyle in remote villages in the late twentieth century – 24; modern technological access, social services, economy; the continuing whale hunt – 20; practices in the whale hunt – 4, 11, 13, 48; sheep population – 6, 13; importance of wool – 13

- 264–5

religion in the Faroe Islands – 15, 20; diversity in religious devotion – 15, 34; religion in Denmark – 10, 50; religion and LGBT rights – 29; children born to single parents – 37

- 265

- 265–6

anti-immigrant political parties in Europe – 3, 7; mass shooting in Norway – 9, 36, 39; homogeneity in the Faroe Islands – 15; growing immigrant population 20; dropping birthrate – 20; Faroese women leaving, and the “imported bride” phenomenon – 45; international responses to immigrants – 27; Faroese attitudes on immigration – 38

- 266–7

closeness with neighbors, and visiting practices – 49; close family relationships – 17; the idealized concept of the Faroese childhood – 17

- 268

the existence and role of the maternity nurse in Denmark – 31

- 268–9

maternity nurses’ responsibilities – 31

- 269

Faroese and American infant mortality rates – 43

- 270–1

increasing numbers of foreign brides – 45; Faroese women leaving, and the “imported bride” phenomenon – 2; marriage migration practices – 5; quality of immigrant marriages – 21; immigrant rights and resources – 28

- 271

LGBT marriage in Denmark – 1

- 272–3

recommendations regarding drinking and smoking during pregnancy – 41; Faroese drinking habits – 13, 24

- 273

sources of water pollution – 30, 45; the importance of avoiding whale and certain fish while pregnant – 18, 19

- 274

immigrant education and employment – 21

- 275

naming laws in other societies – 22, 23; popular Faroese names – 20

- 276

- 277

women working part-time – 20

- 278

breastfeeding recommendations – 41; maternity nurse assistance with breastfeeding – 31

- 279–80

sleep recommendations – 40

- 280–1

benefits of and beliefs about babies sleeping outdoors – 26, 42; closeness among villagers and awareness of strangers – 13

- 281

arrest of Danish woman in New York – 32

- 281–2

- 284–5

children’s freedom to play independently, and the concept of the idyllic Faroese childhood – 16, 17

- 285

birds of the Faroe Islands – 33

- 286

disciplining children – 17

- 287

- 287–8

families’ decisions to attend church, Christian practices in schools – 13

- 289

early school attendance – 14

- 289–90

educational practices, controversies, and rates of graduation – 14, 16

- 290

Danish attitudes about the Faroese – 49

- 290–1

Faroese language – 15; learning traditions in school – 14; the chain dance – 13

- 291

- 292

concept of the Faroe Islands as a “children’s paradise” – 17

Sources Cited – Chapter 9

Metrics

Altmetric attention score

Full text views

Full text views help Loading metrics...

Loading metrics...

* Views captured on Cambridge Core between #date#. This data will be updated every 24 hours.

Usage data cannot currently be displayed.

Accessibility standard: Unknown

Why this information is here

This section outlines the accessibility features of this content - including support for screen readers, full keyboard navigation and high-contrast display options. This may not be relevant for you.

Accessibility Information

Accessibility compliance for the PDF of this book is currently unknown and may be updated in the future.