Series Preface

The Elements in Forensic Linguistics series from Cambridge University Press publishes across five main topic areas (1) investigative and forensic text analysis; (2) the study of spoken linguistic practices in legal contexts; (3) the linguistic analysis of written legal texts; (4) Interdisciplinary research in related fields; (5) Historical development and reflection often through explorations of the origins, development and scope of the field in various countries and regions. Doxxing Discourse by Carmen Lee provides a sociolegal and ethical study of the practice of ‘doxxing’, of openly documenting or revealing a hidden identity, in the context of the Hong Kong extradition protest movements 2019–2020. In this context, Lee argues that doxxing becomes conceptualised as an attempt at public shaming individuals from the policing and security forces.

Taking a critical discourse studies approach this Element examines doxxing, as a discursive action and through a variety of standpoint examines the construction of the doxxing by those who are engaging in the activity, as well as by the media and official and legal standpoints. As doxxing of police and security officers became criminalised in the Hong Kong context this Element sets out how the act of doxxing was the legitimated and justified by those engaging in the activity. This clash between the legal constructions and the protester constructions provides a picture of a fascinating struggle over the notion of public interest, and in turn a new ideological take on the debate between everyday and legal meanings.

This Element then takes the local context of the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests and through this opens out debates that may become increasingly relevant as doxxing might become a tactic for consideration in other jurisdictions, where policing, legal and executive powers attract potential resistance and protest. It makes an exciting addition to the series.

1 What Is Doxxing?

During the 2019–2020 anti-extradition bill protests in Hong Kong, the personal data of thousands of police officers were published on various social media and online forums. Protesters and bystanders have described these actions as seeking justice in response to police violence against protesters at the protest sites. Similar incidents of doxxing have unfolded across the globe in recent years. In China, a high-profile case in March 2025 involved the thirteen-year-old daughter of Baidu’s vice president allegedly doxxing a pregnant woman during an online dispute about a K-pop star, resulting in the disclosure of her workplace details and incidents of online harassment targeting the woman’s family.Footnote 1 Around the same time, the website Dogequest disclosed the personal information of Tesla owners and employees of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) in protest against Elon Musk, which was followed by incidents of vandalism against Tesla properties.Footnote 2

These are incidents of what is now known as doxxing, defined as the act of deliberately seeking and publishing someone’s personal information without their consent, often with malicious intent, such as shaming or punishing targets for their alleged wrongdoings. The information disclosed can include doxxed targets’ names, home and work addresses, phone numbers, financial records, and other sensitive data. The term “doxxing” (or “doxing”) originates from “docs,” short form for “documents.” The phrase “dropping documents” or “dropping dox” was a form of revenge in 1990s hacker culture. It involved uncovering and exposing the identity of people who fostered anonymity (Douglas, Reference Douglas2016, p. 200). Today, one does not need to be a hacker to collect and expose others’ personal data. With people massively sharing their own lives online, their personal information can be easily gathered and disclosed by others. Victims of doxxing can extend beyond the original targets to their families, friends, and related social networks.

Douglas (Reference Douglas2016) classifies doxxing into three major categories: deanonymizing doxxing, the release of personal information to reveal the identity of a formerly anonymous individual; targeting doxxing, the disclosure of personal information that locates the target’s physical location or contact details, which were previously private; and delegitimizing doxxing, revealing intimate personal information that damages the reputation of an individual. Building on Douglas’ categorization, Anderson and Wood (Reference Anderson and Wood2021) provide a finer-grained typology of doxxing based on motives and the types of loss and harm caused to victims. The seven mutually nonexclusive motivations are:

(i) Extortion doxxing: disclosing or threatening to disclose someone’s personal information in order to gain financial or other benefits.

(ii) Silencing doxxing: doxxing to intimidate someone into withdrawing from an online forum or silencing them from participating in the discussion.

(iii) Retribution doxxing: a common type of doxxing motivated by a desire to punish someone for perceived wrongdoings. The four incidents described at the beginning of this Section are to different extents forms of retribution.

(iv) Controlling doxxing: this type of doxxing aims to manipulate targets’ behavior. This is commonly used in the context of coercive control within intimate partner violence.

(v) Reputation-building doxxing: skillfully collecting and publishing personal data to gain acceptance within a group or subculture. For instance, a hacker might doxx a competitor to demonstrate their hacking skills to earn respect within the hacker community.

(vi) Unintentional doxxing: doxxing that occurs without malicious intent, often due to carelessness or lack of privacy awareness.

(vii) Public interest doxxing: doxxing driven by the belief that disclosing personally identifiable or sensitive information serves the public good. For example, publishing the identities of those involved in corruption to hold them accountable.

As can be seen, not all instances of doxxing are motivated by malice. Despite its potential to cause psychological or physical harm to victims, doxxing has been used as a tool for social justice and morality. In mainland China, the Human Flesh Search Engine (人肉搜尋), that is, netizens collectively gathering and publishing targets’ personal information, has reportedly uncovered such illegal acts as corruption of government officials, resulting in doxxed targets being fired or arrested (Gao, Reference Gao2016).

Defining doxxing is not a straightforward matter, especially when it comes to journalistic reporting of personal data in the interest of the public. In December 2022, Elon Musk accused a group of tech journalists of doxxing him by reporting on a Twitter account (@ElonJet) that tracked his private jet using publicly available data. As a result, Musk suspended the journalists’ Twitter accounts. However, many argued that the journalists engaged in legitimate reporting and that Musk’s banning of the journalists’ accounts undermined freedom of expression (Mauran, Reference Mauran2022). This incident illustrates that on social media, the boundaries between doxxing and legitimate reporting become increasingly blurry, particularly when celebrities and public figures are involved.

1.1 Digital Vigilantism and Doxxing

Doxxing is closely linked to digital vigilantism, or digilantism, defined as “a process where citizens are collectively offended by other citizen activity, and coordinate retaliation on mobile devices and social platforms” (Trottier, Reference Trottier2017, p. 55). This “weaponised visibility” involves “naming and shaming” to expose, shame, and punish individuals, often resulting in enduring psychological and physical harm to targets. Those engaging in digilantism take justice into their own hands to address perceived wrongdoings.

The affordances of digital media – anonymity, global reach, and ease of sharing – have empowered ordinary web users to act as digilantes. Crucially, as society becomes increasingly mediatized and connected, one does not need to be a hacker to retrieve and share others’ information publicly online. As soon as people post content to their social media profiles, whether it is intended to be shared privately or publicly, they are already exposing themselves to an unknown and unintended audience. For example, a “private” Facebook post intended for friends only can easily be reshared by a friend to an unexpected audience. This phenomenon is called the “context collapse” of social media, that is, the “collapse of infinite possible contexts” into one, with an “infinitely ambiguous audience” (Wesch, Reference Wesch2009, p. 23). The diminishing of contextual boundaries enables digilantes to weaponize everyday personal data. The widespread availability of personal data and the ease of sharing information have made doxxing a powerful tool for digilantes to achieve various purposes. In recent years, doxxing has become a common tactic for grassroots activism. For example, in the Hong Kong 2019–2020 protests, targets of political doxxing included politicians, activists, police officers, and journalists (Lee, Reference Lee2020).

The impact of doxxing extends beyond privacy invasion to psychological distress, reputation damage, and even physical harm to the victims. Digital affordances, characterized by “spreadability” (ease of sharing and circulation), “searchability” (ability to search and find content), and “visibility” (ability to make content visible to specific audiences) (boyd, Reference boyd and Papacharissi2010, p. 43), make “forgetness” almost impossible, that is, the shared information remains accessible and visible indefinitely online (Garcés-Conejos Blitvich, Reference Garcés-Conejos Blitvich2022). The repeated resharing and persistent disclosure of personal information online can endanger victims and subject them to ongoing scrutiny.

1.2 Anti-Doxxing Laws

In response to the surge of doxxing cases in recent years, legal measures have been implemented in various countries and jurisdictions to regulate doxxing. While some jurisdictions rely on existing laws, others introduce new or amended legislation to prohibit doxxing offences.

In Australia, the Parliament passed the Privacy and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2024 under the Criminal Code Act 1995 to formally criminalize doxxing. This Act covers two new doxxing-related offences: one is for general doxxing, with a penalty of up to six years of imprisonment, and another is for doxxing based on protected characteristics such as race and religion, with a penalty of up to seven years in prison (Parliament of Australia, 2024).

The legal implications of doxxing in the United States are more complex and continue to be contested. Unlike some jurisdictions, there is currently no comprehensive federal anti-doxxing law, and the act of publishing someone’s personal information is generally protected under the First Amendment. However, doxxing can lose constitutional protection when it constitutes “true threats” or involves “incitement to imminent lawless action” (Cremins, Reference Cremins2024). As of 2025, about twenty states have enacted specific anti-doxxing legislation with varying scope and definitions. However, there remain constitutional tensions as many state laws may conflict with First Amendment protections due to their broad scope. The US case demonstrates the typical and ongoing tension between protecting individuals’ rights to privacy and preserving freedom of expression (for details, see Cremins, Reference Cremins2024).

In Hong Kong, the context of this study, an anti-doxxing law was introduced under the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (PDPO) in response to the rise in doxxing cases during the 2019 protests. The law is enacted under a two-tier structure: (i) a summary offence for disclosing personal data without consent with intent to cause harm, liable to a fine of HK$100,000 and up to two years in prison (Section 64(3A)); and (ii) an indictable offence, whereby, in addition to what is stated in the first-tier offence, the disclosure causes harm. The offence is punishable by a maximum fine of HK$1,000,000 and up to five years of imprisonment (Section 64(3C)). The Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data (PCPD) has also been granted more power to investigate and prosecute doxxing offenders (PCPD, n.d.).

Many jurisdictions are yet to implement a specific anti-doxxing law. In some countries, existing laws have been updated to accommodate the changing landscape of technology that shapes online offences. The UK does not have any specific anti-doxxing law to date. Doxxing-related practices such as harassment and unauthorized personal data disclosure are prosecuted under existing laws, including the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, the Malicious Communications Act 1988, and the Data Protection Act 2018 (Crown Prosecution Service, 2024).

Even with these legal measures, applying the doxxing law in real cases remains a challenge. First, it is difficult to strike a balance between protecting individuals’ privacy and people’s right to free speech. In addition, the affordances of digital media, such as users communicating anonymously and sharing information across multiple platforms, have made it difficult to track down those truly responsible for malicious doxxing. A further complication involves the varying interpretations of legal terms like “intent” and “harm” between institutions and lay actors, sometimes even leading to redefinitions of doxxing that reframe and legitimize harmful actions, as will be demonstrated in Section 5.

1.3 Doxxing as a Social Practice: A Turn to Language and Discourse

The challenge in defining doxxing stems from its multifaceted nature, which is best understood through the lens of social practice. As Trottier (Reference Trottier2017, p. 68) argues, doxxing as a tool of digilantism “should not be regarded as an aberration from other digital media practices, but instead located on a continuum of forms of user-led policing and citizenship.” The leakage of Tesla employees’ data by Dogequest described at the beginning of this Section exemplifies how data sharing is weaponized as a tool of protest and retribution under the name of public interest and social justice. In other words, doxxing is not an isolated phenomenon; rather, it is situated in a continuum of practices enacted and amplified by digital media affordances and digital cultural practices that encourage massive sharing and bottom-up policing.

A limited body of academic research has conceptualized and investigated doxxing as a behavioral, psychological, and ethical matter. Scholars from such disciplines as sociology, communication studies, law, psychology, and information science have examined the motives behind doxxing, the methods employed by doxxers, and the consequences and harm caused (Douglas, Reference Douglas2016; Trottier, Reference Trottier2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chan and Cheung2019; Anderson & Wood, Reference Anderson and Wood2021; Cheung, Reference Cheung, Bailey, Flynn and Henry2021; Huey et al., Reference Huey, Ferguson and Towns2025). Despite much of online doxxing being enacted through written comments or messages posted on digital platforms, little attention is paid to the role of language that shapes the phenomenon.

This Element is amongst the first to contribute a language and discourse perspective to the growing body of doxxing scholarship. It conceptualizes doxxing as a social practice primarily enacted, represented, and sustained through discourse (Lee, Reference Lee2020). Drawing on insights from multiple analytical tools such as netnography, critical discourse analysis (CDA), and pragmatics, this Element aims to unpack the discursive construction of doxxing practices. It offers a comprehensive analysis of a range of discourse features surrounding doxxing. It also reveals how ordinary people and institutions construct, negotiate, and contest its meaning.

This Element is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the theoretical underpinnings and methodological approaches for researching doxxing as language and discourse. Drawing on the case of doxxing in Hong Kong, Section 3 examines the linguistic and discourse strategies employed in doxxing-related online discussions. Sections 4 and 5 continue to explore attitudes and perceptions toward doxxing, as well as how it is interpreted by participants, based on survey and interview data. This Element also examines selected legal documents of doxxing to reveal the limitations of top-down legal and institutional discourses surrounding doxxing. Section 6 concludes the Element by reflecting on the theoretical, methodological, and policy implications of the study. By analyzing the discursive strategies and public perceptions of doxxing, the study seeks to offer insights into the intersection of language, power, and policy in digital landscapes.

2 Researching Doxxing as a Discursive Action

2.1 Doxxing Discourse: Insights from Critical Discourse Studies

Having established doxxing as a social practice in Section 1, the central argument of this section, and in this Element as a whole, is that doxxing should be understood as not just an online behavior, but also a discursive action. This is because doxxing and its related practices are primarily produced, circulated, and sustained through language and discourse. Michel Foucault’s conceptualization of discourse as a system of thought that shapes social reality (Foucault, Reference Foucault1972) provides a framework for understanding doxxing as discourse. Foucault argues that discourse is not merely language, but it is also a system of power that produces and regulates knowledge, identities, and (un)acceptable behaviors. In view of this, doxxing can be understood as operating within such discursive systems, where the act of disclosing personal information becomes a “technology of power” (Foucault, Reference Foucault1971) to punish targets through public shaming, resistance, or silencing. For example, during the US Capitol riot in 2021, doxxing of rioters was used as a form of counter-discourse against far-right extremism, which was often framed through discourses of resistance. Foucault’s conceptualization of power and discourse aligns with doxxing’s dual role in both exposing those who participated in the riot and constructing collective identities (e.g., “defenders of democracy” vs. “threats to democracy”) as the events unfolded.

The field of Critical Discourse Studies (CDS), or what is commonly referred to as Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA),Footnote 3 provides a suitable theoretical framework for examining doxxing because it views discourse as a social practice that both shapes and is shaped by the social actors, contexts, institutions, and social structures in which it occurs (Wodak, Reference Wodak, Leung and Street2014, p. 303). CDS is also “problem-oriented and interdisciplinary” in approach (Wodak & Meyer, Reference Wodak, Meyer, Wodak and Meyer2009, p. 2), which makes it particularly relevant in understanding a complex social practice like doxxing. This Element understands discourses of and about doxxing through the lens of CDS, in that people’s actions and attitudes toward doxxing and its related activities are shaped by the everyday discourse that we routinely encounter in online and offline communicative landscapes (Teo, Reference Teo2000). As a method of analyzing language and discourse, CDA is a contextualized approach that examines how language is used to justify, legitimize, and normalize acts of publicly exposing personal information, thereby revealing the complex social dynamics that underpin the practice of doxxing.

Although to date there has been limited discourse analysis of doxxing (but see Lee, Reference Lee2020), there is an established body of language-based research analyzing various linguistic dimensions of conflicts, aggression, and abusive behavior in digital media. For example, linguistic devices such as irony, metaphors, and nonstandard orthography are commonly employed in enacting flaming and hate speech online (Herring, Reference Herring1999; Assimakopoulos et al., Reference Assimakopoulos, Baider and Millar2017). In addition to overtly aggressive linguistic markers such as profanity and racial slurs, scholars have also observed an emerging pattern of “covert hate speech,” that is, utterances that do not carry explicitly offensive language while causing harm (Baider & Constantinou, Reference Baider and Constantinou2020), such as dehumanizing metaphors like referring to refugees or immigrants as “mice” or “worms.” At the macro-level of discourse practices, researchers adopt CDA to understand the strategic ways in which ideologies are represented through verbal aggression online. For example, a delegitimation strategy, such as rejecting the professionalism of certain social groups, is often employed to justify verbal abuse online (Kagan et al., Reference Kagan, Kagan, Pinson and Schler2019). Focusing on trolling, Hardaker (Reference Hardaker2013) identifies a range of covert discourse strategies, such as the strategy of “digress,” that is, “straying away from the purpose of the discussion.” These covert strategies may seem harmless on the surface, but can still cause emotional discomfort to targets and possibly lead to offline physical abuse.

A closely relevant body of work that informs this Element’s focus on doxxing discourse is Garcés-Conejos Blitvich’s (Reference Garcés-Conejos Blitvich, Johansson, Tanskanen and Chovanec2021, Reference Garcés-Conejos Blitvich2022) extensive research on online public shaming (OPS). Through digital discourse analysis and netnographic approaches, Garcés-Conejos Blitvich (Reference Garcés-Conejos Blitvich2022) discusses six cases of OPS in the United States involving the exposure of perceived racism against visible minorities, where doxxing is a key tactic. Informed by pragmatic theories of (im)politeness, Garcés-Conejos Blitvich argues that OPS reflects emotional and coercive impoliteness, where heightened emotions like anger and indignation are used to punish targets’ perceived wrongdoings, which is racism in this case. The research reveals the important role of language for bottom-up social regulation and resistance. It also informs the understanding of the dynamics of doxxing for the research reported in this Element, which aims to examine the complex interplay between discourse, morality, and social justice in online environments.

In the context of digital media, CDA offers a toolkit for digital discourse researchers to scrutinize the complex power relationships among social actors in online public spaces. It also helps unpack the role of digital activism and counter-discourses online in shaping offline socio-political events. Notably, Social Media Critical Discourse Studies (SMCDS) is an emerging approach to discourse analysis that addresses the changing dynamics of discursive power in social media (Bouvier & Machin, Reference Bouvier, Machin, Guillem and Toula2020; KhosraviNik, Reference KhosraviNik2023). SMCDS argues that social media has transformed the traditional power relationship between authors and readers, allowing for increased reader agency in engaging with and responding to political content through online commenting. SMCDS also examines how social media users actively consume and produce political discourse to influence public opinion and political discussions. This study also applies CDA to analyze online doxxing discourses, so as to uncover how netizens and bystanders use language to justify or normalize doxxing.

2.2 Intertextuality and Recontextualization

Doxxing is primarily constructed through intertextuality, as the act of publicly exposing an individual’s personal information depends on doxxers’ sourcing, organizing, disseminating, and resharing a range of texts from both online (e.g., targets’ social media profiles) and offline (e.g., public records). Intertextuality, the ways in which texts echo, incorporate, and respond to previous texts and voices, is a core concept in CDS (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough2003). The notion has been applied in a range of data types and contexts, including the discourse of online hate speech and racism, where speakers mobilize intertextual references to increase the authority of their own stance (Hodsdon-Champeon, Reference Hodsdon-Champeon2010) or to perform what has been called “intertextual impoliteness” (Badarneh, Reference Badarneh2020). Intertextuality also demonstrates the ways in which texts are inherently historical, in that a text always “responds to, reaccentuates, and reworks past texts” to “make history” (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough1992, p. 270). The historicity and temporality of texts are particularly relevant to the current study of doxxing. To doxx someone is to create and recreate the target’s personal history through the assemblage of prior discourses that may be publicly or privately available online or offline.

In digital media, intertextuality is amplified by social media affordances. Users become “intertextual operators” (Androutsopoulos, Reference Androutsopoulos and Coupland2010) who effortlessly modify and appropriate texts across media platforms through copy-pasting, taking screenshots, forwarding, and resharing. Personal and other private information that was intended for private sharing on one platform can now be easily reappropriated and repurposed, reinforced by context collapse, as discussed in Section 1. This repurposing of texts is enabled by recontextualization, a process where social actions are represented and transformed by discourses in new contexts (van Leeuwen & Wodak, Reference Van Leeuwen and Wodak1999; van Leeuwen, Reference Van Leeuwen, Wodak and Meyer2009). In digital media, recontextualization occurs when content is shared across platforms and adapted to fresh discursive settings (Androutsopoulos, Reference Androutsopoulos2014). Recontextualization plays a crucial role in digitally mediated socio-political protests, where semiotic resources are rapidly recontextualized and distributed across physical and online spaces (Khosravinik & Unger, Reference KhosraviNik and Unger2016). In addition, social media’s real name policy and users’ limited privacy awareness further facilitate the unexpected circulation of personal data, contributing to the proliferation of doxxing (Wauters et al., Reference Wauters, Lievens and Valcke2014).

2.3 Discourse Strategies of Legitimation, Justification, and Argumentation

Another concept from CDS that informs the current study is legitimation. As previously noted, doxxing is a criminal offence in some regions, including Hong Kong, and may fall under data privacy laws elsewhere that do not have specific anti-doxxing legislation. Given this background, it is reasonable to expect that in online forums, those engaged in doxxing or doxxing-related practices, including active users and bystanders, may manipulate or strategically deploy their language to continue exposing others’ personal information without appearing to engage in illegal activities. A CDA approach allows researchers to uncover covert discourse strategies that justify, legitimize, or even normalize the controversial, and at times legally ambiguous, behavior of doxxing.

Legitimation discourse, as defined by Reyes (Reference Reyes2011, p. 782), refers to “the process by which speakers accredit or license a type of social behavior.” Van Leeuwen (Reference Van Leeuwen2007, p. 92) outlines four primary categories of legitimation discourse: authorization (reference to authority, figures, or tradition), moral evaluation (references to value systems), rationalization (references to goals and uses of institutionalized social action), and mythopoesis (narratives that reward legitimate actions). These categories were initially developed to understand top-down legitimation processes of institutional actions, based on the assumption that “[l]egitimation is always the legitimation of the practices of specific institutional orders,” such as policy documents that justify compulsory education (Van Leeuwen, Reference Van Leeuwen2007, p. 92). However, legitimation strategies are equally applicable in grassroots contexts, where counter-discourses seek to resist or subvert mainstream institutional narratives (Feltwell et al., Reference Feltwell, Vines and Salt2017).

Legitimation is closely tied to the discourse process of justification, which refers to the linguistic realization of “defensive reactions to implied or inferred accusations” (Wodak, Reference Wodak1990, p. 132). Both legitimation and justification rely on argumentation strategies that allow the speaker or writer to position themselves as unbiased actors, “free of prejudice or even as a victim” (Wodak, Reference Wodak, Graddol and Thomas1995, p. 8; see also Reyes, Reference Reyes2011). In CDA, argumentation involves providing reasons that serve to explain social actions in order to (de)legitimize them. Legitimation discourse is also goal-oriented. Reyes (Reference Reyes2011) observes that one of the most common goals of legitimation is to seek approval or acceptance from others by presenting potentially controversial action as serving a wider group or community. This Element demonstrates how the legitimation of doxxing emerges as a meaningful strategy employed by both ordinary people and institutions.

Against this conceptual and theoretical backdrop, this Element examines the discursive nature of doxxing and its implications for forensic linguistics research. Using the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests as a case study, the Element explores how doxxing practices are discursively represented and constructed in both online discussions and institutional documents. The overarching research questions guiding this inquiry are: How do online participants, bystanders, and policymakers discursively construct, represent, and perceive doxxing? What are the implications of these discursive constructions for understanding and addressing doxxing?

2.4 Context: The 2019–2020 Hong Kong Protests and Doxxing of Police Officers

In 2019–2020, shortly before the global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hong Kong witnessed one of its largest socio-political movements in history. The anti-extradition law amendment bill protests (also known as the Anti-ELAB movement) were a year-long pro-democracy movement against the proposed amendment of an extradition bill that would allow transfer of fugitives to any jurisdiction that Hong Kong lacks a formal agreement with, including mainland China. This sparked widespread concerns over potential threats to Hong Kong’s legal autonomy as a special administrative region of China. The movement is believed to be leaderless and self-organized mainly on digital communication via social media and mobile apps such as Telegram and traditional online forums like LIHKG (Lee, Reference Lee2020).

Despite the formal withdrawal of the bill in October 2019, tensions between the protesters, the government, and the police continued to escalate. Riot police were criticized for using excessive force, such as tear gas and rubber bullets, to disperse the protesters.Footnote 4 The protesters urged the government to meet their five demands, which included establishing an independent commission of inquiry into police use of violence. Media reports also revealed certain police officers concealing their identification numbers and badges and covering up their faces while on duty on the protest sites.Footnote 5 When the police became unidentifiable, this lack of transparency made it challenging for protesters to file complaints against them.

As the tension between the activists and the police surged, numerous doxxing incidents emerged on online forums and social media, notably the Hong Kong-based forum LIHKG, where the personal information of numerous police officers and their families was exposed. As of the end of 2019, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data (PCPD) of Hong Kong received over 1,500 complaints that involved the doxxing of police officers and their families (PCPD, 2020). Information being disclosed includes their full names, phone numbers, home addresses, spouses’ and children’s names, and schools attended, and so on, which was published along with pictures of the targets extracted from their personal social media profiles (Forsyth, Reference Forsyth2020). What followed was a series of public shaming and harassment of these officers and their families online and offline (SCMP, 2019). As a result, the High Court granted an interim injunction order to ban all unauthorized publishing or disclosure of the personal data of police officers and their families. For a while, a handful of doxxing-related posts were removed from LIHKG.

Doxxing in Hong Kong predates the rise of social media. However, it became more widespread during the 2019 protests. As a result, Hong Kong’s legal framework surrounding doxxing has evolved significantly. Based on a preliminary review of 124 media reports on doxxing between 2015 and 2022, four key phases of doxxing in Hong Kong have been identified:

(i) Early concerns (2015–2016): In 2015, the government called for restricting access to public registers to protect privacy. As the Legislative Council Election approached in 2016, there were increasing cases of doxxing identified. Hong Kong Privacy Commissioner Stephen Wong urged internet users to respect the privacy of individuals.

(ii) Legal measures and academic research (2017–2018): In November 2017, a financial consultant was charged with using others’ personal data in direct marketing without consent. Personal data obtained from public domains were also protected under the Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (PDPO). Academics also called for legal responses against cyberbullying. For example, Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chan and Cheung2018) noted that 30 percent of secondary school students had experienced doxxing.

(iii) Protests (2019–2020): During the protests, several arrests were made for disclosing personal data of police officers and their family members. Notably, a thirty-two-year-old man was arrested for exposing the data of over 2,300 police officers on the Telegram channel “DadFindBoy” (Maragkou, Reference Maragkou2019). In October 2019, an interim injunction was granted to ban doxxing against police officers and their families.

(iv) Criminalization (2021 to date): The Personal Data (Privacy) (Amendment) Ordinance 2021 was passed on October 8, 2021, to criminalize doxxing. The first arrest under this law was made in December 2021 in which a thirty-one-year-old man was accused of posting the personal details of the victim with whom he had monetary feud.

2.5 Data Collection and Analysis

The data and analysis discussed in this Element are based on a research project funded by the Hong Kong government’s Public Policy Research Funding Scheme (PPR project code: 2021.A4.075.21A). The original study examines how doxxing is defined, perceived, and justified online and among young people in Hong Kong, comparing these perspectives with legal and government definitions to inform education policy development that enhances critical awareness of doxxing. The research design for this study adopts a discourse-centred online ethnographic (DCOE) approach (Androutsopoulos, Reference Androutsopoulos2008), combining systematic observation of online discursive practices and insider perspectives from interviews with internet users. The study adopts a multi-staged design with four main phases of research activities:

PHASE 1: Contextualizing and Revealing Discourses of and about Doxxing

Prior to data collection, an extensive and up-to-date review of 124 media reports from various local newspapers in Hong Kong to understand how doxxing in the city evolved in recent years. With the introduction of the doxxing law in October 2021, reviewing news reports allowed the research team to gather timely and the most relevant empirical evidence of known doxxing cases in Hong Kong.

Following this preliminary review, a corpus of authentic online interactions was compiled from LIHKG (連登), a popular Hong Kong-based forum, known for its involvement in high-profile cases of cyberbullying and doxxing (SCMP, 2019). The primary language of data on LIHKG is Cantonese, a variety of Chinese spoken by over 90 percent of Hong Kong citizens. The forum is predominantly used by Hong Kongers and is often referred to as the Hong Kong version of Reddit or 4Chan (Wong, Reference Wong2024). A keyword search for “起底” (doxxing) was conducted via the LIHKG search engine to identify relevant threads. The selection and review of threads focused on content that involved exposing personal data, categorized according to types of doxxing outlined by Douglas (Reference Douglas2016) and Anderson & Wood (Reference Anderson and Wood2021) – deanonymizing, targeting, delegitimizing, extortion, silencing, retribution, controlling, reputation-building, unintentional doxxing, and doxxing in the public interest.

The corpus consisted of forty-three threads and 28,943 comments. Two types of posts were collected:

Name-and-shame incidents: These involve the disclosure of an individual’s personal information for “naming and shaming.”

Reactive posts and comments to doxxing-related news: These posts and comments reflect users’ attitudes and perceptions, providing insights into how doxxing is discussed and justified online.

These forum posts and comments illustrate how doxxing is discursively represented in their authentic context of communication. CDA is employed to unpack the implicit argumentation strategies that legitimize and justify doxxing. Analyzing the linguistic and discursive realizations of these posts reveals how doxxing is framed and how such discursive framing may be manipulated to legitimize doxxing in a covert manner. The aim of this qualitative discourse analysis is not to provide an exhaustive analysis of doxxing-related discourse or a single definition of doxxing. Instead, it seeks to offer a situated understanding of doxxing and reveal its fluidity and complexity. Given that the meaning of doxxing varies among users on LIHKG (Lee, Reference Lee2020), the analysis focuses on how doxxing is (re)defined and justified by different social actors.

PHASE 2: Attitudes and Perceptions: Surveying and Interviewing University Students

Having obtained an informed and up-to-date understanding of the discursive nature of doxxing in Phase 1, Phase 2 of the study aimed to gather data on young people’s attitudes and perceptions of doxxing. Undergraduate students from Hong Kong universities were chosen as participants for two reasons: (i) the limited research of doxxing in Hong Kong focuses primarily on teenagers (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chan and Cheung2019); and (ii) university students were active participants in local online forums where doxxing incidents are evident (SCMP, 2019). Although these students may not have been directly involved in doxxing, it was reasonable to assume that they were aware of doxxing-related discussions before and after the social unrest.

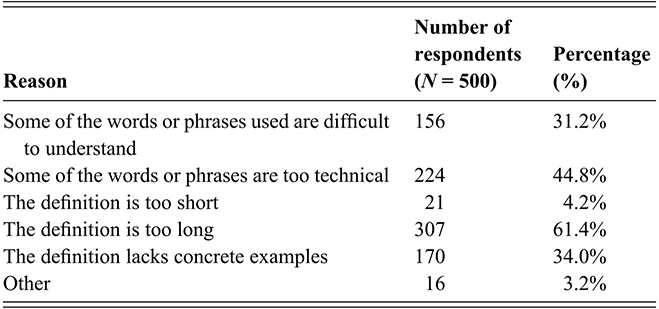

An online questionnaire was administered to undergraduate students from different universities in Hong Kong to provide a snapshot of trends in their attitudes and perceptions. Our target respondents were all residents in Hong Kong, aged between 18 and 22. Members of this age group were chosen as they were the most active internet users (99.8 percent of penetration) according to HKSAR statistics in 2019. Although other age groups are equally vulnerable to doxxing, research has shown that young people are more likely to respond negatively to cyberbullying, such as self-harm and attempted suicide (John et al., Reference John, Glendenning and Marchant2018).

The questionnaire consisted of fifteen questions and took approximately 15–20 minutes to complete. It was hosted on the free survey service Qualtrics and distributed via university mass email services, personal contacts, and virtual class visits. By the end of March 2022, 500 respondents had completed the questionnaire.

The key set of questions takes reference from Assimakopoulos et al.’s (Reference Assimakopoulos, Baider and Millar2017) questionnaire on perceptions of hate speech, which consists of the following parts:

(i) Likert scale ratings of selected definitions and statements about doxxing, so as to elicit respondents’ perceptions of the issue;

(ii) Likert scale ratings of acceptability of authentic examples of doxxing discourse identified on LIHKG collected in Phase 1 of the study;

(iii) Multiple choice questions on respondents’ overall experience with doxxing (e.g., whether they have been victims or perpetrators, or both);

(iv) Participants’ level of understanding of the newly introduced doxxing law at the time and their rating of the clarity of the language used in the law.

Combining questionnaire and interviews has proven effective in much cyberbullying research to “capture broader perspectives and to pursue issues of interest with more targeted and in-depth questions” (Assimakopoulos et al., Reference Assimakopoulos, Baider and Millar2017, p. 20). Following the online survey, thirteen participants were invited to focus-group interviews to discuss their understanding and experience of doxxing. These participants agreed to be interviewed as indicated in their survey responses and were selected based on their survey answers to reflect a broad range of doxxing experiences and attitudes, so as to ensure a comprehensive analysis. The interview protocol was developed based on the research aims and the survey responses, focusing on discussions of participants’ definitions of doxxing and reasons for their ratings.

As the study was conducted during COVID-19, all the interviews were conducted on Zoom as face-to-face meetings were not possible. Each focus group discussion lasted between sixty and ninety minutes. This was an initial discussion of participants’ general perceptions of doxxing in Hong Kong. Additionally, five semi-structured individual interviews were conducted to follow up on specific themes emerging from the focus groups as well as specific survey responses. Participants were requested to share their first-hand experience as victims or perpetrators of doxxing upon their consent. Each interview lasted around sixty minutes. The combination of both focus-group and individual interviews enhances data richness by contextualizing the phenomenon under research and revealing specific themes in richer detail (Lambert & Loiselle, Reference Lambert and Loiselle2008). All of the interviews were conducted in Cantonese and recorded on Zoom.

Ethics clearance from the Chinese University of Hong Kong and informed consent from all participants were obtained. Participant identities are fully anonymized using pseudonyms (e.g., Respondent A, B, etc.) in this Element to prevent re-identification and potential exposure, particularly given the sensitive socio-political nature of the research context. To mitigate potential risk, research data were stored securely with limited access to the core research team members only.

PHASE 3: Analyzing Institutional Discourses of Doxxing

The third phase of the study examined how doxxing is represented in legal documents and government discourse. The aim is to compare institutional definitions with the discourses constructed by netizens and university students in the first two phases of the study. This comparative analysis serves to identify potential mismatches between the interpretation of doxxing among young people and institutional definitions, with the hope of facilitating more accurate and effective policy-making. A total of seventy-seven documents related to key doxxing cases in Hong Kong were collected, including:

– Fifty-three documents from government and PCPD publications, such as press releases on the PCPD website, documents and guidelines published by the Cyber Security and Technology Crime Bureau (CSTCB) of the Hong Kong Police Force, and resources published on the Education Bureau (EDB) website;

– Twenty-four legal and policy documents, the revised PDPO on doxxing, reports, and publications by The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong and the Legislative Council.

2.6 Data Processing and Coding

The study adopted an iterative research process, where the research activities were constantly refined as the project progressed. Multiple data sources were triangulated to understand a particular theme from multiple perspectives. The online questionnaire results were generated through descriptive statistics. The purpose of the questionnaire findings is (i) to gain general insights into the participants’ experience, perceptions, and attitudes of doxxing; (ii) to identify suitable participants for Phase 2 of the study; and (iii) to complement and contextualize the results of the qualitative discourse analysis in subsequent phases of the study. All the LIHKG posts, interview transcripts, and policy documents were imported to the qualitative analysis software MAXQDA to create a database of analyzable texts. Recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim by a student assistant. Codes were developed inductively from the data.

Coding and analysis were performed in two stages: The first was a thematic analysis. Following van Dijk’s (Reference van Dijk2009) semantic macro-analysis, the research team performed both open and axial coding to identify salient themes and subcategories in the data. The second stage of coding paid close attention to the linguistic and discursive strategies using CDA tools and concepts. This phase of coding identified argumentation strategies related to the dissemination, legitimation, and naturalization of doxxing. This was achieved through repeated close and critical readings of the linguistic and content choices made in the LIHKG data, the interviews, and policy documents. The CDA was primarily informed by groundwork related to doxxing by the researcher (Lee, Reference Lee2020) and previous research on online aggressive behavior by other researchers (e.g., Assimakopoulos et al., Reference Assimakopoulos, Baider and Millar2017; Baider & Constantinou, Reference Baider and Constantinou2020). The interpretation of discourse practices was also situated within the broader socio-historical background of Hong Kong to uncover the ideologies that shape the participants’ perceptions. The findings from analyses of forum posts and interviews were compared with institutional discourses. The purpose of this comparative analysis is to reveal possible mismatches between young people and the official understanding of doxxing.

To ensure rigor and transparency, the data were coded and repeatedly reviewed by both the author and a full-time research assistant. Regular consultation sessions were also held with trained student assistants, who are also regular users of LIHKG, to interpret context-specific language found on the forum. This collaborative approach helped validate interpretations in the identification of doxxing incidents and discourse patterns. Coding memos were also produced to document major decisions made in the coding, analysis, and interpretation of data. The memos also noted theoretical or conceptual connections that emerged from the data. Patterns of digital practices and discourse strategies, and similarities and differences among social actors (i.e., whether they take up similar or different strategies when representing the same instance of doxxing) were noted. The coding matrix was drafted and constantly reviewed and revised by all members of the project team (see Appendix for the full coding scheme).

3 Language and Discourse Strategies of Doxxing Discussions Online

This section analyzes the language and discourse strategies employed in online discussions of and about doxxing, as well as LIHKG users’ reactions to doxxing-related news. The analytical focus is on how forum participants construct, justify, and legitimize the practice. Informed by CDA concepts, this section discusses the interplay of intertextuality, linguistic choices, and legitimation strategies in shaping doxxing practices.

It is important to note that the data analyzed in this Element does not immediately warrant classification as illegal doxxing, nor is it the intention of this Element to determine legal consequences. Rather, the focus is on the ways language and discourse may be manipulated or reframed when forum users attempt to disclose others’ personal information. The posts to be examined may contain information about unknown parties, reactions to news related to doxxing and its legal context in Hong Kong, or reposts of news about doxxing incidents.

3.1 Doxxing as Intertextual and Recontextualized Discourse

To illustrate what a doxxing incident may look like on LIHKG, consider a thread with the subject line, “There’s a dog that really wants to be famous. Will you help it or not?!!” This thread exemplifies the structure and rhetorical strategies often used to expose personal information for public scrutiny. The various components of this post will first be unpacked to reveal how doxxing operates intertextually within the forum’s discursive norms. Doing so also helps to contextualize the data discussed in the subsequent sections.

The euphemistic title hints at doxxing behavior. First, the metaphor of a “dog” serves as a derogatory reference to the target – a police officer – a common dehumanizing label used by activists and protesters. The playful and ironic tone downplays the seriousness of the content, which involves disclosing personal information for the purpose of naming and shaming, a common tactic in online shaming and digilantism (Murumaa-Mengel & Muuli, Reference Murumaa-Mengel and Muuli2021). The post also calls to action, “Will you help it or not?!!,” which actively invites participation from other forum users.

The majority of the initial posts in this thread are represented by the most direct and explicit form of intertextuality, or what Fairclough (Reference Fairclough1992) calls “manifest intertextuality.” The post is a lengthy one, comprising nine screenshots taken from a police officer’s Facebook profile. The thread comprises three intertextual components:

– Part 1 of the thread includes a screenshot of the officer’s photo from his Facebook account, captioned with his full name and family members’ names (wife, son) in Chinese, which reads, “Name of dog: [full name of the officer]; Family history of dog: A mother, a wife called [name of wife], a son called [name of son].”

– Part 2 of the post features a collage of the officer’s Facebook screenshots and online comment exchanges, including a political debate with a student and a meme mocking the police commissioner.

– Part 3 of the post contains five private photos of the officer’s family and friends from Facebook.

3.1.1 Multimodal Intertextuality in Doxxing: Screenshots as Personal History

The post described demonstrates that online doxxing relies heavily on multimodal intertextuality, where screenshots, primarily from social media and private communication, act as the primary tool for recontextualizing antecedent texts. As shown, the post is created by making intertextual references to images and texts from the police officer’s Facebook feed, which in itself contains additional layers of multimodal texts. The shared material also includes text-based comments from the officer’s Facebook friends, embedding heteroglossic voices from multiple actors (Androutsopoulos, Reference Androutsopoulos and Coupland2010). Instead of creating intertextual links through words only, the antecedent texts, whether they are originally images or words, are represented as screenshot images, creating text-as-image and image-as-image intertextual relations.

In disclosing the police officer’s and his family’s identities, all three of Douglas’ (Reference Douglas2016) categories of doxxing are evident. To de-anonymize, the full names of the officer, his son, and his wife are revealed in the Facebook screenshots. These names are intertextual both internally to the names captured in the screenshots in this post, and externally to the officer’s Facebook site outside the forum, and to their real-world legal identities.

This post also illustrates targeting doxxing (Douglas, Reference Douglas2016). Although no information about home address is shared, the screenshots reveal the officer’s Facebook account name, and thus anyone can look him up and locate him “virtually” with an online search. Douglas (Reference Douglas2016) makes a clear distinction between de-anonymizing and targeting doxxing in that the former reveals a connection between a pseudonym and one’s legal identity, while the latter aims to physically locate someone. In this post, the disclosure of the officer’s Facebook profile is not only to reveal the officer’s real name, but to ensure that he becomes “locatable” at least virtually. When the officer is identified online, abusers are likely to locate his other social media profiles, with the aim of inducing further public scrutiny or cyberbullying. This practice is clearly connected to “call-out” and “cancel” culture, in that netizens rapidly share and reshare targets’ personal information for public shaming because of their alleged wrongdoing (Clark, Reference Clark2020).

3.1.2 Unattributed Intertextuality and Assumption

Delegitimizing is the primary motive behind this post. By sharing screenshots of the officer’s social media comments on political topics, his words are recontextualized to frame him as ideologically aligned with the Hong Kong authorities. This act not only exposes the officer’s political stance but also invites further scrutiny from forum participants.

Alongside the screenshots, the thread initiator adds the caption:

You don’t even know how to use Facebook. Stop messing with other people’s children

This requires some unpacking. The pronoun “you” establishes a cohesive link to the officer in the image, creating a simulated dialogue between the author and the officer. This remark points to the fact that the officer has made his own Facebook posts public, implying he is responsible for his own exposure. The adverb “even” (連 lin4 in Cantonese) presupposes that, as a police officer, he should be more media literate and sensitive to online privacy. There is also an implicit attribution to Facebook’s privacy policy, which allows users to control who can view their posts. The second part of the comment implicitly references the police’s use of violence against protesters, many of whom are young people, thus framing the officer’s actions as “messing with other people’s children.”

The purpose of this intertextual relation is not to criticize the officer’s privacy insensitivity but to condemn him as a police officer supporting the extradition bill, which most forum participants oppose. The negative evaluation of the officer’s competence in using Facebook also creates an unattributed intertextual connection to the government’s stance on protecting police privacy despite alleged misconduct (SCMP, 2019). This is not intertextuality per se but rather what Fairclough (Reference Fairclough2003) terms assumption, which depends on meanings that are “shared and can be taken as given” (p.55). Although it is unclear if the officer was involved in violent crackdowns, the forum participants’ common ground is the assumption that most police officers have “messed with other people’s children,” thus deserving no respect. These intertextual links and assumptions reinforce the binary opposition between “Us” (activists) and “Them” (police, government) (Oddo, Reference Oddo2011), creating a context where doxxing police officers is legitimized and justified.

3.2 Linguistic Re-Appropriation of Doxxing

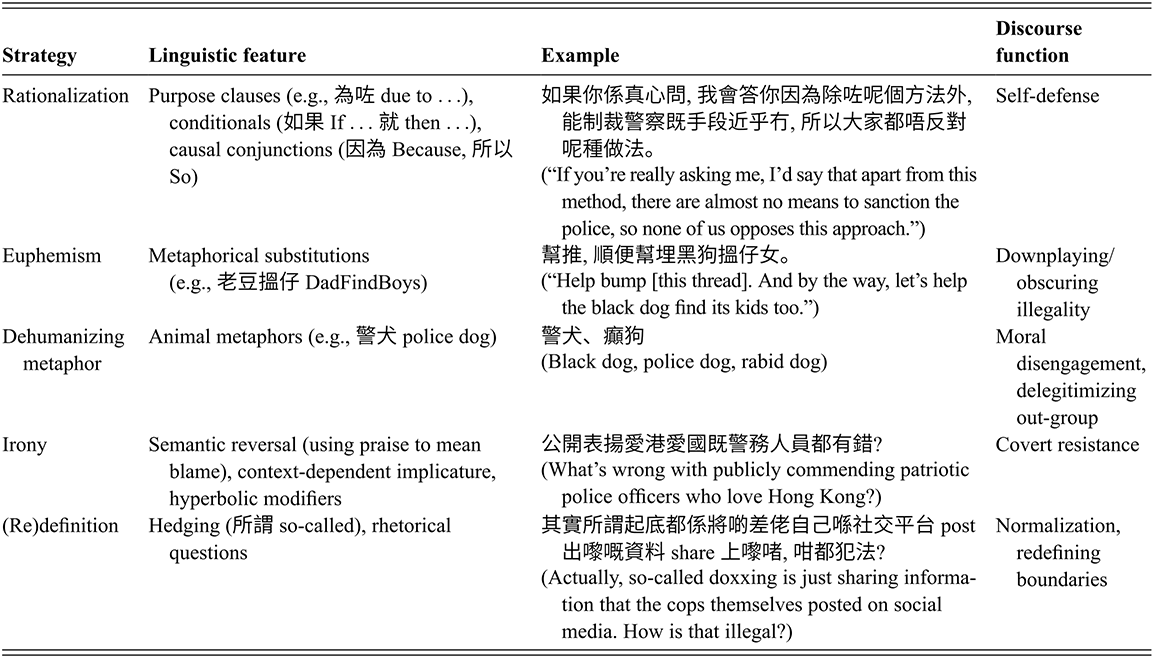

This section examines how doxxing-related practices are linguistically reframed by LIHKG users through strategic language use. Drawing on concepts of CDA, the analysis focuses on how forum participants creatively re-appropriate language to construct doxxing as morally acceptable. Three recurring linguistic devices are identified across the dataset – metaphor, euphemism, and irony – which work together to downplay the perceived harm of doxxing.

3.2.1 Dehumanizing Metaphors

In CDA, metaphors are a key linguistic device to convey ideology in discursive legitimation of discriminatory and negative othering discourses (Koller, Reference Koller and Hart2020; Hart, Reference Hart2021). In the LIHKG forum data, dehumanizing metaphors involving “dog” imagery emerge as a recurring strategy to delegitimize all Hong Kong police officers, regardless of their level of involvement in the protests. The discourse analysis reveals multiple linguistic variants referring to “dogs,” including:

黑狗 (Black dog)

警犬 (Police dog)

癲狗 (Rabid dog)

警甴/狗官 (Police cockroach/dog official)

走狗 (running dog)

支那狗 (China dog)

魔犬 (demon dog)

These dog metaphors, or any animal metaphors, serve to dehumanize police officers by positioning them “‘lower down’ in the Great Chain of Being” (Hart, Reference Hart2021, p. 232). By framing officers as less than human, these metaphors facilitate “soft hate” strategies in online aggression. Dehumanization also enacts what Bandura et al. (Reference Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara and Pastorelli1996) refer to as “moral disengagement” (Bandura et al., Reference Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara and Pastorelli1996). According to Bandura et al., acts of moral disengagement, such as blame attribution, displacement of responsibility, and dehumanization, allow individuals to justify or rationalize harmful or unethical behavior, such as doxxing, thereby disengaging their moral self-sanctions and avoiding feelings of guilt.

3.2.2 Euphemism

The use of euphemism serves as a strategic linguistic device to legitimize or downplay the harmful nature of doxxing. One notable example is the term 老豆搵仔 (or “DadFindBoy” in English, literally “Dad looking for son”), specifically used to refer to deanonymizing of masked or unidentifiable police officers during the protests. The “DadFindBoy” channel, a Telegram group, was used to gather and publish personal information about police officers and their families. The channel’s name metaphorically frames the act of doxxing as a familial search, where “dads” (activists) are looking for their lost “sons” (police officers). Despite the arrest of the administrator of the “DadFindBoy” channel on Telegram, the LIHKG participants still continue to use this term when they refer to the doxxing of police. This reframing downplays the severity of doxxing by portraying it as a kind act of reunification rather than a malicious behavior.

A related example is “幫推 順便幫埋黑狗搵仔女” (“Help bump [this thread]. And by the way, let’s help the black dog find its kids too.”). This comment embeds a disguised call for doxxing within a seemingly harmless request. The term 黑狗 (“black dog”) is a derogatory term for police officers, in which “black” evokes a negative association with 黑社會 (black society, a reference to triads or gangsters), implying that the police are as morally corrupted as criminals. Framing doxxing as an act of helping a dog reunite with its offspring, doxxing is recast as a service rather than an abusive act of privacy invasion. The casual tone (“by the way”) further trivializes the severity of the doxxing, presenting it as a secondary, almost incidental, activity. Another common protest-related euphemistic expression is 發夢 (“dreaming”), which was used as a euphemism for attending or recounting experiences at the protests (Leung, Reference Leung2019). Protesters would say they “dreamed” they were at a protest site and discuss their experiences without having to directly admit involvement in potentially illegal activities. For example, a commenter wrote, “發夢夢見 開槍黑警” (“In my dream, I saw a black cop shooting”). This allows the user to share their first-hand experience at the protest sites without explicitly saying that they actually saw the shooting.

As can be seen, these euphemistic expressions are also metaphorical, which can be referred to as metaphorical euphemism. In political discourse, metaphorical euphemism serves to soften controversial issues and frame them positively (Crespo-Fernández, Reference Crespo-Fernández2018). Similarly, in doxxing-related discussions on LIHKG, euphemisms such as dreaming help obscure the potentially malicious intent and harmful consequences of doxxing practices.

3.2.3 Irony

According to Fairclough (Reference Fairclough2003), irony is intertextual because it means “saying one thing but meaning another” that “echoes someone else’s utterance” (p. 123). Irony in doxxing discussions serves multiple functions. For one thing, it allows users to challenge and subvert dominant narratives in a covert manner. Such covertness becomes a protective mechanism as it conveys resistance without overtly challenging authorities and legal boundaries. In the LIHKG forum data, being doxxed is ironically framed as an “honor,” as illustrated in the following examples:

(1) 黑警係正義嘅

所以要公開表揚佢哋大家

(“Black cops are righteous; Therefore, we should publicly commend them, everyone.”)

(2) 公開表揚愛港愛國既警務人員都有錯?

(“What’s wrong with publicly commending patriotic police officers who love Hong Kong?”)

(3) Good job 請繼續宣揚警隊英勇事跡

(“Good job, please continue to promote the police force’s heroic deeds.”)

Examples (1) to (3) carry a seemingly positive undertone, using verbs of praise such as 表揚 (commend/praise) and 宣揚 (promote/propagate). However, the intent of these comments is expected to be interpreted through the audience’s awareness of the context of communication. The immediate context of the discussion threads, that is, posts reacting to the newly introduced doxxing law, coupled with the broader social context of escalating conflicts between protesters and the police, makes it clear that the police are meant to be condemned, not praised. The meanings of these comments are uncovered within a frame consistent with the forum participants’ negative stance toward the police. The writers of these posts assume that their audience will recognize “praising” as an ironic reference to doxxing. The ironic effect is created through the exact opposite of what is said is what is meant (Assimakopoulos et al., Reference Assimakopoulos, Baider and Millar2017). Here, “praising” or “promoting” an officer is a coded reference to the act of doxxing, that is, publicly revealing personal information as a form of social sanction. The irony is thus constructed through the deliberate reversal of meaning: what is said as praise is meant as condemnation.

3.3 Legitimation Discourse Strategies

Legitimation strategies, as theorized within CDA, aim to address the fundamental questions of “Why should we do this?” or “Why should we do this in this way?” (Van Leeuwen, Reference Van Leeuwen2007). There are four primary conceptual categories in Van Leeuwen’s (Reference Van Leeuwen2007) legitimation framework: authorization (reference to authority), moral evaluation (reference to value systems), rationalization (reference to goals and uses), and mythopoesis (legitimation through storytelling). These strategies operate through complex discursive manipulations in order to transform potentially controversial topics or actions into socially acceptable practices. When discursively framing the doxxing of police officers on LIHKG, participants provide arguments to answer “Why do we doxx?” or “Why is doxxing the right thing to do?”

3.3.1 Rationalization: Doxxing as Self-Defense

Rationalization is one of the most explicit forms of legitimation (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough2003). When rationalizing an action, reasons for the action are given based on principles of right or wrong, or norm conformity (Van Leeuwen, Reference Van Leeuwen2007). Objective moral evaluation of actors is also given to justify one’s controversial action (Oddo, Reference Oddo2011). Legitimizing doxxing through rationalization is also achieved through stating the purpose and purposiveness of the action in order to answer the question, “Why is disclosing someone else’s personal data morally right and effective?” Rationalization discourse explains an action by reference to “goals and uses” (Van Leeuwen, Reference Van Leeuwen2007). The aim of rationalizing an action is to frame it as a sensible decision, as “the right thing to do.”

Specific to the LIHKG data, the rationalization strategy answers the question of “What is the purpose of doxxing the police?” Commenters provide rational reasons to explain doxxing as serving real purposes, as illustrated in examples (4) and (5):

(4) 你搞人地個仔

人地咪搞返你個仔囉

(“You mess with someone else’s son. That’s why they mess with your son in return.”)

(5) 如果你係真心問

我會答你因為除左呢個方法外

能制裁警察既手段近乎冇

所以大家都唔反對呢種做法

(“If you’re genuinely asking me, I’d say that apart from this method (doxxing), there are almost no means to sanction the police, so none of us opposes this approach.”)

In both examples, doxxing is rationalized in the name of a form of reciprocity, self-defense, and as the only approach to achieve justice. Example (4) is a reactive comment to a British police officer’s family being doxxed, including the school his children attended, leading to physical abuse and bullying at the school. The commenter rationalizes doxxing as an “equal” response to what police have done to others’ children during the protests. It directly presents doxxing as justified retaliation (“mess with your son in return”). The implied logic here is that if the police have done wrong to the young protesters (who are also others’ children), it is acceptable for their supporters to respond in kind. This rationalization seeks to legitimize doxxing by framing it as reciprocal justice.

Example (5) rationalizes doxxing by scrutinizing the power imbalance between civilians and the police. To the activists, the police are unprofessional, biased, and possess excessive power, and there is no way for the public to challenge their authority. By emphasizing this power imbalance, the commenter conveys a sense of helplessness, thus justifying the use of unconventional tactics such as doxxing as the only way to achieve justice. By stating that there are “almost no means to sanction the police,” this example positions doxxing as a last resort where civilians can exercise their agency. The statement that “none of us opposes” doxxing suggests the collective sentiments among activists and supporters that doxxing is a necessary tool.

3.3.2 (Re)definition: Neutralizing Doxxing

(Re-)definition is a “theoretical legitimation” strategy where actions are legitimized not in terms of purposes and effectiveness, but through defining an action in terms of “another, moralized activity” (Van Leeuwen, Reference Van Leeuwen2007, p. 103). Van Leeuwen originally categorizes definition as a form of rationalization. However, in the context of LIHKG, (re-)defining doxxing is a salient practice that deserves its own category. For one thing, facing the possibility of their controversial posts being removed by authorities, it is important for the forum participants to develop a shared interpretation of what doxxing is or, more importantly, what it is not.

(6) 其實所謂起底都係將啲差佬自己喺社交平台 post 出嚟嘅資料 share 上嚟啫 咁都犯法

(“Actually, so-called doxxing is just sharing information that the cops themselves posted on social media. How is that illegal?”)

(7) 政治既思維係特別 D

連登既所謂起底

只係將放係 public domain 既資料整理

(“Political thinking is different. LIHKG’s so-called doxxing is just organizing information already in the public domain.”)

Examples (6) and (7) redefine doxxing as the redistribution of publicly available data, which downplays its malicious nature. In the LIHKG data, doxxing is often prefixed with 所謂 (“so-called”), which signals the writers’ distancing from the negative connotations of the word. A common argumentation strategy in the data is to claim that the exposed information is already made public by the targets, which serves to neutralize doxxing as morally acceptable (characterizing it as “sharing information,” “organizing information”), rather than as a violation of privacy.

Once redefined and neutralized as mere information sharing, the commenters proceed to delegitimize the doxxing law, suggesting that it is too stringent. The rhetorical question 咁都犯法 (“How is that illegal?”) in Example (6) marks the commenter’s epistemic stance and skepticism toward the ambiguous legal definition of doxxing. Stylistically, rhetorical questions are a powerful linguistic device to focus “on the argument in the message, thereby enhancing the goal, which is persuasion” (Ademilokun & Taiwo, Reference Ademilokun and Taiwo2013, p. 447). In this case, the writer employs a rhetorical question to persuade other forum participants that doxxing is not illegal. Rhetorical questions are often juxtaposed with an implicit intertextual reference to external voices – in this case, to the legal discourse that criminalizes doxxing behavior, allowing the writer to indirectly challenge the authority of the law.

Example (7) further contrasts “political thinking” (政治既思維) with what the commenter sees as overly narrow legal definitions of doxxing. This juxtaposition foregrounds a perceived mismatch between lay and official interpretations of legal terms. Such redefinition creates a shared interpretive framework within the forum community, which enables participants to collectively justify their actions within the broader attempts to detach doxxing from its harmful intent.

Some participants normalize doxxing by defining it as “the way things are” (Van Leeuwen, Reference Van Leeuwen2007). Normalization is a discourse strategy that frames ideologies and social practices as normal and commonplace, thus attributing what would have been unacceptable behavior a more neutral quality (see Rheindorf, Reference Rheindorf2019). In the case of legitimizing doxxing, expressions such as “many,” “inevitable” are often used to frame doxxing as commonplace, thus not requiring legal attention.

(8) 不是網民的專利, 很多機構 (包括政府機構如秘密警察) 都可起底

(“It’s not something exclusive to internet users; many organizations (including government agencies like secret police) can also doxx people.”)

(9) 在資訊科技過於發達的環境下, 這件事很難避免

(“In a world where information technology is overly advanced, this kind of thing (doxxing) is inevitable.”)

Examples (8) and (9) legitimize doxxing as a common and inevitable outcome of technological advancement. Example (8) describes doxxing as “不是網民的專利” (“not something exclusive to internet users”) and a common practice by “很多機構” (“many organizations”). By stating that doxxing is not unique to online communities but is also engaged in by institutions, the act of doxxing is given a high degree of authority and legitimacy. Using examples of government agencies like the secret police, again, serves to detach doxxing from its malicious intent, implying that if government institutions can do it, then it must be acceptable for civilians to follow suit.

Example (9) frames doxxing as a natural byproduct of technological advancement. By presenting doxxing as inevitable (很難避免) in the digital age, the commenter shifts focus away from individual responsibility to broader social changes. Similar to the function of Example (8), this comment serves to reduce the severity of doxxing, framing it as an ordinary part of life rather than a deliberate invasion of privacy. The strategies identified here also parallel Sykes and Matza’s (Reference Matza and Sykes1957) “techniques of neutralization” in their analysis of juvenile delinquency, where individuals use specific rhetorical devices to temporarily override moral constraints that would normally prevent illegitimate behavior.

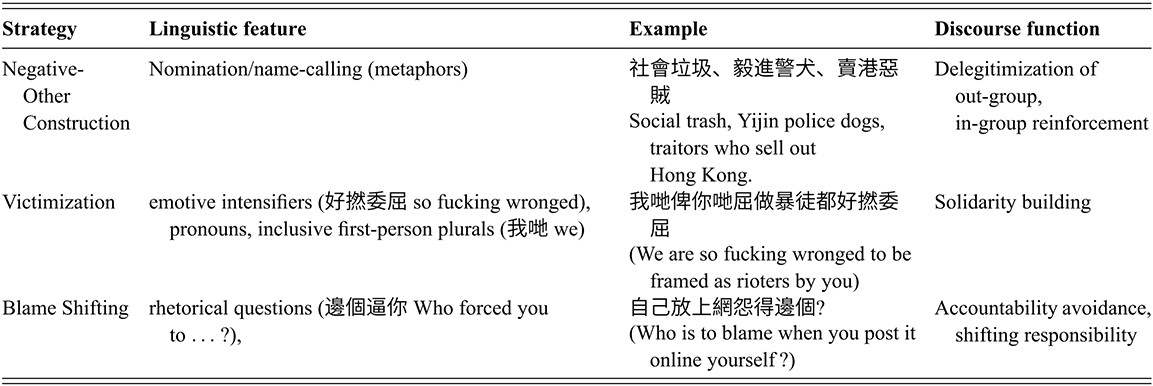

3.3.3 Negative-Other Construction: Degrading Authorities

By attributing negative qualities to the out-group, actors are able to construct a “negative-Other” representation, thus positioning themselves as morally superior or “in the right.” Such negative constructions are often linguistically realized by attaching negative labels to the out-group, or through negative moral evaluation of them (Wodak, Reference Wodak, Wodak and Meyer2001). Common linguistic strategies include dehumanizing the “out-group” and attacking the out-group’s intelligence or competence, and so on. In the LIHKG forum data, the police and the government are often represented in negative terms. This serves to unify forum users by establishing a shared target and reinforcing in-group solidarity.

There are several ways through which forum participants attribute negative qualities to police officers to legitimize doxxing. First, the out-group (i.e., the police) is linguistically realized by nomination strategy, that is, the use of membership categorization devices to define out-groups (Wodak, Reference Wodak, Wodak and Meyer2001), such as dehumanizing the police as 垃圾 (“trash”) and 警犬 (“police dog”) in example (10). Second, “police” (警) is often premodified by “black” (黑), which means gangsters in Cantonese (Choy, Reference Choy2020). The colloquial expression has been frequently used since July 2019, when the police allegedly colluded with gangsters to attack protesters in a metro station. 毅進警犬 (“Yijin police dogs”) in example (10) not only dehumanizes the police, but also mocks their educational background by referencing the Yijin (毅進) diploma programme for underachieving students who are not eligible for university admission, implying they are uneducated or illiterate. Example (11) even further frames Yijin as a syndrome, implying that police officers who are suffering from it as intelligence-deficient. It is reported that many police officers graduated from that programme.Footnote 6 The activists, the majority of whom are university students, were calling the police “毅進仔” (“Yijin guys”) to delegitimize their professionalism.

(10) 社會垃圾 毅進警犬 賣港惡賊

(“Social trash, Yijin police dogs, traitors who sell out Hong Kong.”)

(11) 毅氏綜合症呀! 毅進仔! IQ高唔高過 50 呀?

(“Yijin syndrome! Yijin boy! Is your IQ not higher than 50?”)

By mocking the police’s intelligence, labeling them as “social trash,” and implying their low IQ, these constructions position the police, that is, law enforcement, as inferior and illegitimate, thereby justifying doxxing as a form of moral rectification.

Lexical choices in examples (12) and (13), such as “lawless,” “oppression,” “bandit,” and “murderer,” help foreground the police’s use of excessive violence, thus holding them accountable and framing them as deserving to be doxxed.

(12) 無天無法, 專責打壓

濫用私刑, 猶在賊營

(“Lawless, specializing in oppression, abusing private punishment, still in the bandit camp”)

(13) 殺人兇手 警員 xxx [name of officer]

(“Murderer, Police Officer [name]”)

Example (12) is also noteworthy in that it employs a poetic style resembling traditional Chinese couplets. The use of four four-character lines with rhymes creates a poetic effect, which adds to the rhetorical power of the negative-Other representation. In contrast, example (13) is more direct and confrontational. By labeling a specific officer as a “murderer,” this comment explicitly accuses the police of extreme violence, positioning them as immoral and deserving of doxxing.

The targeted out-group in the data includes not only the police, but also government officials involved in implementing the doxxing law, notably the Privacy Commissioner, who demanded more authority “to order the relevant social platforms or websites to remove or stop uploading content and posts that involved doxxing” (SCMP, 2019). Reacting to this news report, one forum user wrote:

(14) 私隱專員, 掹大隻眼睇清楚喇!

全部係X生自己 post 上 facebook 㗎!

全部係佢自己 set public 㗎!唔該你地派人去教人班毅進仔點用 facebook先啦!

(“Privacy Commissioner, open your eyes and see clearly! Everything on Facebook was posted by Mr. X himself! He made everything public himself! Please send someone to teach those Yijin boys how to use Facebook first!”)

Example (14) delegitimizes the Privacy Commissioner through multiple means. First, his professional judgment and credibility are being challenged. The imperative and directive speech act 掹大隻眼睇清楚 (“Open your eyes and see clearly”) is a Cantonese colloquial expression, implying that he has been negligent or mistaken in his assessment of doxxing cases. Second, through implicit redefinitions of “public” and “private,” the commenter legitimizes doxxing by holding the targeted officer accountable – 全部係佢自己 set public 㗎 “He made everything public himself”) – emphasizing that the information was willingly shared by the target on a public platform. By focusing on the target’s own action, the commenter suggests that the Privacy Commissioner is misinterpreting the situation by equating re-sharing something on public Facebook pages with doxxing.

Blame shifting is also at play in Example (14). Blame shifting or blame avoidance, as a discourse strategy, involves redirecting or shifting responsibility for negative outcomes from oneself or one’s group to another individual or group. This strategy is commonly used in political communication to evade accountability and protect one’s reputation. For example, politicians may employ blame shifting by presenting others, such as opposing parties as accountable for societal issues or crises (Hansson & Page, Reference Hansson and Page2024). In the LIHKG forum data, blame shifting often occurs as counter-discourse, when forum participants redirect the responsibility to doxxed targets as the ones who first disclosed their own personal information online. The commenter in (14) shifts the blame to the police as he made his Facebook public, and away from those actually sharing the information and shaming the target.

When responsibilities are shifted to the targets, their “victim” status has also been undermined. Discourse can be used to construct and contest victim identities. In examples (15) to (17), the commenters are actively working to undermine the victim status of the doxxed individuals by highlighting their own agency (e.g., carelessness) in making the information public.

(15) 自己放上網怨得邊個

(“Who is to blame when you post it online yourself”?)

(16) 邊個逼你放個人資料上社交媒體

(“No one forces you to post personal information on social media.”)

(17) 起底無問題, 只係上網唔小心

(“Doxxing isn’t the issue, it’s just people being careless online.”)